Women & sustainable development

- Introduction

- Activity 1

- Activity 2

- Activity 3

- Activity 4

- Reflection

Introduction

Development affects people in different parts of the world in different ways. It also affects people differently, depending whether they are male or female. Being aware of this, and taking it into account in development planning and action is known today as practicing a ‘gender perspective’.

Generally speaking, there have been a number of improvements to women’s lives in the past twenty years. For example, female life expectancy is increasing; more girls are going to school; more women are in the paid workforce; and, many countries have introduced laws to protect women’s rights. However, the gender divide remains. There has been “no breakthrough in women’s participation in decision-making processes and little progress in legislation in favour of women’s rights to own land and other property”, according to Mr. Kofi Annan, in his role as Secretary General of the United Nations.

This module explores women’s experiences of development in different parts of the world. It also explores ways in which women from a number of countries are working to promote sustainable development in their communities and how these ideas can be integrated into a teaching programme.

Objectives

- To evaluate the way development impacts on women in varying situations;

- To identify with women’s concerns about development;

- To understand the importance of accelerating the pace of change in women’s development;

- To appreciate the way women are working for a sustainable future in their own communities; and

- To identify opportunities for incorporating issues and activities from the module into a teaching programme.

Activities

- Holding up half the sky

- Women’s experiences of development

- The International Platform for Action

- Working for a sustainable future

- Reflection

References

Davis, C. (2007) Ask EarthTrends: Why is gender equality important for sustainable development?

De Pauli, L. (ed) (2000) Women’s Empowerment and Economic Justice: Reflecting on Experience in Latin America and the Caribbean, UNIFEM, New York.

Elson, D. (ed) (2000) Progress of the World’s Women, UNIFEM, New York.

Heward, C. and Nunwaree, S. (eds) (1999) Gender, Education and Development: Beyond Access to Empowerment, Zed Books, London.

International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development (IJISD) (2009) Special Issue on Gender and Sustainable Development, 4(2/3).

Mies, M. and Shiva, V. (1993) Ecofeminism, Spinifex, Melbourne.

Seager, J. (2009) The Atlas of Women in the World, Earthscan, London.

Shiva, V. (1989) Staying Alive, Zed Press, London.

Third Session of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2004) Enhancing the Role of Indigenous Women in Sustainable Development, IFAD Experience with Indigenous Women in Latin America and Asia, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

Tisdale, C. (2001) Sustainable development, gender inequality and human resource capital, International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 2(Jan), pp. 178-192.

United Nations (2005) The World’s Women: Trends and Statistics, United Nations Statistics Division, New York.

UNDP (2004) Gender and Energy for Sustainable Development. A Toolkit and Resource Guide.

UNFPA and WEDO (2009) Climate Change Connections. A Resource Kit on Climate, Population and Gender.

UNFPA (2009) State of World Population 2009. Facing a Changing World: Women, Population and Climate.

Women’s Environment and Development Organisation (1999) Risks, Rights and Reforms: A 50-Country Survey Assessing Government Actions Five Years After the International Conference on Population and Development, WEDO, New York.

Visvanathan, N., Duggan, L., Nisonoff, L. and Wiegersma, N. (eds) (1996) The Women, Gender and Development Reader, Zed Books.

Internet Sites

Many Internet sites provide resources on gender and sustainabilty. These sites contain much statistical information, case studies of current trends and links to related sites.

International Development Research Centre: Gender and Sustainable Development Unit

UNESCO – Society for International Development: Environmental Justice and Gender Programme

UNIFEM – The United Nations Development Fund for Women

Women’s Environment and Development Organisation

WomenWatch: The United Nations Internet Gateway on the Advancement and Empowerment of Women

Credits

This module was written for UNESCO by Margaret Calder and John Fien from material written by Jane Williamson-Fien in Teaching for a Sustainable World (UNESCO – UNEP International Environmental Education Programmes) and from the World Resources Institute teaching unit, Women and Sustainable Development.

Holding up half the sky

Women constitute one half of the world’s population,

they do two-thirds of the world’s work,

they earn one tenth of the world’s income and

they own one hundredth of the world’s property including land.

Source: United Nations (1979) State of the World’s Women, Voulntary Fund for the UN Decade for Women, New York.

Women have always been – and remain – the deciding influence on the quality of life and well-being of their families and communities. They are the primary care-givers and the managers of natural resources, including food, shelter and consumption of goods, in most cultures. In addition, many women also have jobs and have careers in the formal economy.

Women’s responsibilities place them in a unique position to improve human and economic well-being, and to conserve and maintain the natural environment. Yet, their needs, their work and their voices are often not considered a priority. As a result, women in many countries do not have equal access to education, health care, employment, land, credit, technology or political power.

The general failure to provide equal opportunities for women to pursue education and economic self-sufficiency has meant that a disproportionate number of women are poor. Without adequate education, many are stuck in low-paying, low-status jobs – if they are able to work outside the home at all. These social barriers – exclusion, low status and poverty – are also barriers to a sustainable future.

Case studies of education and health for women

This activity illustrates these ideas through case studies of women’s education and women’s health around the world.

You may choose to explore one or both of these case studies.

Global patterns of education for women and girls

Secondary Education

This graph shows the percentage of females enrolled in secondary school in different parts of the world, and how the numbers increased between 1975 and 1997.

[Note the marked differences in enrolment rates between countries in the North and the South.]

Click graph for larger image.

Q1: Identify the areas of the world where less than 60% of girls went to secondary school in 1997.

Q2: List two possible reasons why girls typically receive much less schooling than boys?

See sample answers.

Use the tools on Gapminder to learn how girls’ education has fared since 1997.

Adult Literacy

This graph compares female and male adult literacy rates in six areas of the world in 2000.

Click graph for larger image.

Q3: How do literacy rates for women compare with those for men in the regions shown in the graph?

Q4: Which areas have the highest and lowest literacy rates for both women and men?

Q5: In which areas are there the biggest and smallest differences between the literacy rates of women and men?

Q6: Identify three consequences of not being able to read and write.

Q7: List three reasons why you believe it is important for women to become literate.

See sample answers.

Use the tools on Gapminder to learn how adult literacy rates have changed since 1997.

Female Literacy and Population Growth

This graph shows the relationship between female literacy rates and projected population growth rates for 10 countries in different parts of the world.

Click graph for larger image.

Q8: Which five countries have the highest female literacy rates?

Q9: Which five countries have the lowest projected population growth rate?

Q10: What conclusions about educating girls and women can you draw from this pattern?

See sample answers.

See regularly updated statistics on women’s education.

Global patterns of women’s health

Maternal Mortality Rates

This graph shows maternal mortality rates in ten different countries.

[The maternal mortality rate is the number of deaths from pregnancy or childbirth related causes per 100,000 live births.]

Click graph for larger image.

Q11: Which countries have the lowest and highest maternal mortality rates?

Q12: Why are maternal mortality rates a significant social indicator of development?

Q13: What factors might cause maternal death rates to decrease?

See sample answers.

Use the tools on Gapminder to learn about changes in mortality rates in your region or country.

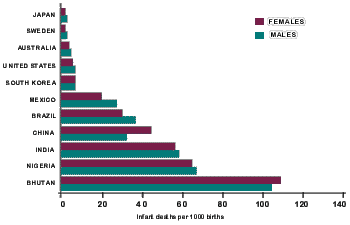

Sex Differences in Infant Mortality

This graph shows infant mortality rates for boys and girls in ten countries around the world.

[Infant mortality rate is the probability of dying before a child’s first birthday, multiplied by 1000.]

Click graph for larger image.

Q14: Which three countries have the highest infant mortality rates?

Q15: Which four countries have the lowest infant mortality rates?

Q16: In which countries are the infant mortality rates higher for girls than boys?

Q17: Which country has the largest gap between female and male infant mortality rates?

Q18: Identify some factors that could explain these differences.

Q19: Identify some factors that could contribute to high infant mortality.

See sample answers.

See regularly updated statistics on women’s health.

Use the tools on Gapminder to learn about the progress on women’s heath indicators around the world.

Women’s health, education and sustainable living

Women tend to be very conscious of any changes in the environment because the health of their families is closely linked to the health of the land, the quality of water and air, and the conservation of forests, fisheries and other natural resources.

Unsustainable patterns of development cause serious health risks for women, especially in reproductive health. These risks increase as women become more active in work outside the home. For example:

- Water pollution in Uzbekistan has led to an increase in birth defects and complications in pregnancy.

- Pesticide exposures in Central Sudan are linked to 22% of hospital stillbirths.

- Air pollution in the Ukraine has been linked to 21% of illnesses affecting women and children.

- One in three women in the USA will be diagnosed with cancer at some time during their lives.

- Nuclear contamination in Chelyabinsk, Russia, has led to a 21% increase in cancer and a 25% increase in birth defects. Half of the population of child-bearing age is sterile.

- In Guatemala, pesticide residues in breast milk are reported to be 250 times the amounts allowed in cow’s milk.

- Many children in China take in DDT from breast milk at levels 10 times higher than internationally accepted levels.

Source: Women’s Environment and Development Organisation (1999) Risks, Rights and Reforms, WEDO, New York.

Education is a solution to health problems such as these. Indeed, there is a high correlation between improved education for girls and improvements in health and in social and economic development.

Educated parents tend to have healthier children. Women are the primary health care providers in society. An estimated 75% of all health care takes place in the home. Therefore, attempts to improve the health of a country’s population must include and empower women. A woman who can read the label on a package of medicine is a more effective health care provider than one who cannot. In fact, surveys in 25 countries in the South show that, all other factors being equal, 1 to 3 years of schooling for a mother can reduce child mortality rates by 15%, as opposed to only 6%, when fathers have the same level of education.

Educated women also tend to have increased decision-making authority within the household.

Education also increases women’s chances of earning an income outside the home – income that can be used to pay for food, clothing, education and health care for their families.

Source: Paden, M. (ed) (1996) Women, World Resources Institute, Washington DC.

Women’s experiences of development

Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity.

The patterns on women’s health and education studied in Activity 1 are evidence that the experience of development varies in different parts of the world. They also show that the results of development are quite different for women and men.

This activity introduces you to a range of women through stories of their experiences of development.

| Sithembiso is a Zimbabwean woman active in sustainable agriculture. | Jane is a farmer in Australia. | ||

| Cathy is a migrant worker from the Philippines who works in Singapore. | Angela is an architect in Stockholm who is concerned about issues of gender and urban design. |

Q20: Identify key aspects of the experience of development of these women.

Q21: Using the stories of these women – and other women you know – analyse the range of impacts of development on women around the world.

- How has development changed the nature of women’s lives and work?

- How similar or different are women’s experiences and concerns as farmers, factory workers and service providers? Why? Use the case studies and the experiences and concerns of women in your country.

- What sort of development would improve the position of the women in the case studies and women in your country?

The International Platform for Action

Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity.

An International Response

The United Nations has convened a number of international conferences to discuss women’s experiences of development. The Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing in 1995.

This conference developed a Platform for Action as “an agenda for women’s empowerment”.

The Beijing Platform for Action identified twelve issues as ‘critical areas of concern’ for women, and on which strategic action was needed by governments, non-government organisations and businesses around the world:

- The persistent and increasing burden of poverty

- Inequalities and inadequacies in, and unequal access to, education and training

- Inequalities and inadequacies in, and unequal access to, health care and related services

- Violence against women

- The effects of armed or other kinds of conflict on women, including those living under foreign occupation

- Inequality in economic structures and policies, in all forms of productive activities and in access to resources

- Inequality between men and women in the sharing of power and decision-making at all levels

- Insufficient mechanisms at all levels to promote the advancement of women

- Lack of respect for, and inadequate promotion and protection of, the human rights of women

- Stereotyping of women and inequality promotion and protection of the human rights of women

- Gender inequalities in the management of natural resources and in the safeguarding of the environment

- Persistent discrimination against, and violation of, the rights of the girl child.

Q22: Which of these 12 concerns are relevant to the experiences of:

- the women in the case studies in Activity 2, and

- women in your country?

UNIFEM

UNIFEM is the section of the United Nations primarily responsible for women and development and encourages the mainstreaming of gender issues in all United Nations’ activities.

UNIFEM believes that the biggest concern facing women is the ‘feminisation of poverty’. It identifies seven main causes of this problem. These are:

- Globalisation

- Low wages

- Traditional approaches to economic development

- Trade liberalisation

- Society’s attitudes towards women

- Cannot travel as freely as men.

- Access to markets

Explain how these factors contribute to the ‘feminisation of poverty’.

The Beijing Platform for Action argued that achieving equality between women and men was needed to address these concerns:

The advancement of women and the achievement of equality between women and men are a matter of human rights. This is a basic condition for social justice, and should not be seen in isolation as just a women’s issue. Indeed, this is the only way to build a sustainable, just and developed society. Empowerment of women and equality between women and men are prerequisites for achieving political, social, economic, cultural and environmental security among all peoples.

Progress Since the Beijing Conference

The Beijing conference may be remembered as the point in history when women took over the international process, injected it with their own ideas and experiences, and then converted it back into local and national actions. Since 1995, women have used the ideas and energy of Beijing to push for progress on many fronts, often through new activist networks that span nations and regions.

They have convinced an increasing number of countries to adopt affirmative action programmes that raise the number of women in politics. In 2000, there were:

- seven women heads of state in the world;

- three heads of government; and

- 145 countries have governments which included women.

Activists in South Africa have lobbied their government to breakdown its budget along gender lines so that women can see who really benefits. In Thailand, the government has prohibited sexual discrimination in its new constitution. In Egypt, women worked with religious leaders to repeal a law allowing rapists who marry their victims to avoid jail.

The Beijing conference also encouraged the UN system to place greater emphasis on gender. It called on UNIFEM, and other UN agencies, to establish the world’s first funding mechanism devoted to supporting projects to eliminate violence against women. Gender units have been set up in many agencies to foster women’s contributions to shaping critical policies and decisions. At UNESCO, women have been considered one of four priority groups since November 1995. After the Beijing conference, the Unit for the Promotion of the Status of Women and Gender Equity was created, and the Agenda for Gender Equity was established to bring gender into all of its programmes and activities, especially in the media, peace, and science and technology education.

Despite the achievements of the past five years, however, women world wide continue to lag behind in almost all areas. According to the UN Division for the Advancement of Women, women’s employment has increased in all regions, but their wages are 50 to 80% of men’s. Up to 80% of refugees fleeing from conflict are women and children. Two-thirds of the world’s illiterates are female, and nearly half the women in the developing world do not meet minimum daily caloric intakes.

A long list of obstacles stands in the way of addressing these issues. Discriminatory attitudes and traditional stereotypes deprive women of resources and continue to prop up the laws, policies and institutions that prevent greater progress. For example, so-called ‘honour killings’ which are committed by men who feel that women have damaged their reputation, are still legal in three countries.

The Beijing Platform is not a legally binding document. Governments follow its recommendations only because it serves their interests to do so, or because women marshal the political power to persuade them to change laws and policies.

While women’s movements and networks have grown in strength and in their ability to work with national and international political systems, they must contend with a growing set of new challenges.

Source: Adapted from UNESCO Sources, No.125, 2000, pp. 4-5.

Beijing +5

In June, 2000 delegates from 180 countries convened at UN headquarters in New York to evaluate progress made since Beijing, agree on obstacles, and map out a set of actions to continue implementing the Platform for Action.

Protracted debates took place over commitments to reproductive health and rights, with the Holy See and a handful of conservative Muslim and Catholic countries attempting to rill back gains by women made on these issues in previous international agreements.

However, for the first time, governments agreed to address the problems of ‘honour killings’ and forced marriages. There was consensus on the need to enact stronger laws against all forms of domestic violence, and to set up quota systems to bring more women into politics. The agreement also contains a reference to the right to inheritance, which has long been disputed by Muslim countries.

Source: Adapted from UNESCO Sources, No.125, 2000, pp. 4-5.

The governments at the Beijing +5 conference agreed to a Final Outcomes Document that reaffirmed their commitments to the Beijing Platform for Action and their plans to make gender equality on a key underlying principle in development. This would include:

- a focus on women’s conditions and basic needs;

- a holistic approach to development based on equal rights;

- promotion and protection of all human rights; and

- government policies, programmes and budget processes that adopt a gender perspective.

… and beyond

Since the Beijing +5 conference there have been a further two global conferences (Beijing +10 and Beijing +15) to mark progress on women’s issues.

The latest of these, Beijing +15, was held in March 2010. The emphasis of the conference was on the sharing of experiences and good practices, with a view to overcoming remaining obstacles and new challenges, including those related to the Millennium Development Goals. In a commemorative event to reflect on the progress since the first conference in Beijing, UN Deputy Secretary-General Asha-Rose Migiro said in her address:

In the past 15 years, understanding has grown that the empowerment of women and girls is not just a goal in itself, but is key to all our international development goals, including the Millennium Development Goals.

The impact of recent multiple global crises on women and girls has further heightened this understanding. We must, therefore, rethink past policies and strategies for growth and development.

The conference adopted a Declaration which contained the following seven resolutions, as priorities for attention over the next 5 years:

- Women, the girl child and HIV/AIDS

- Release of women and children taken hostage, including those subsequently imprisoned, in armed conflicts

- The situation of and assistance to Palestinian women

- Women’s economic empowerment

- Eliminating maternal mortality and morbidity through the empowerment of women

- Strengthening institutional arrangement of the UN for support of gender equality and the empowerment of women by consolidating the four existing UN offices into a composite entity

- Ending female genital mutilation.

Working for a sustainable future

Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity.

In 1999 the Women’s Environment and Development Organisation (WEDO) investigated the progress of 90 countries in addressing women’s rights since the 1995 Women’s Conference in Beijing.

Read an overview of the findings of this survey.

Q23: Identify (i) some of the positive changes and (ii) some of the disappointments in women’s experience of development since the 1995 Women’s Conference. Provide examples and data where available.

Improvements in the rights of women and their access to services such as education are the result of what UNIFEM calls “women’s advocacy worldwide”. That is, they are the result of women working actively in their local communities, and through national and international networks, to improve the life opportunities of all women and their families.

This activity provides an opportunity to meet some of these women.

- Michiko Ishimure of Japan wrote a documentary account of Minamata Disease and organised a civic group to assist victims of the disease.

- Chipko women in north India pledged to save forests from logging.

- Sophie Kiarie in Kenya worked on greening arid areas of Kenya.

- Maria Cherkasova of Russia led a protest against a dam in the Altar Mountains.

Q24: Analyse the contributions of these women to a sustainable future.

- Identify the issues that concern these women.

- What types of strategies did these women use?

- Why do you think these women have been successful?

See other case studies of women working for a sustainable future from the report by the Women’s Environment and Development Organisation.

Reflection

Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity.

Completing the module: Look back through the activities and tasks to check that you have done them all and to change any that you think you can improve now that you have come to the end of the module.

Q25: Identify three reasons why the study of gender and sustainable development should be an important part of every person’s education.

Q26: Identify (i) a subject or syllabus, (ii) a grade level, and (iii) a syllabus topic where the topic of gender and sustainable futures may be taught.

Q27: Identify the name of a woman, women’s group or project that could be used as a case study to illustrate these topics. This could be a case study from this module or one that you know about from your own community or country.

Q28: Explore the following gender issues in your school:

- Are the experiences and contributions of girls and women included in text books used in your school? Are many textbooks written by women?

- Are both boys and girls encouraged to enrol in the same types of classes (social studies, mathematics, science, sports, etc.) in your school? Does the school maintain records of enrolment patterns by gender for each subject area and course?

- Does the rate of participation in programmes for gifted and talented students reflect the gender balance of the school?

- Do the rates of participation in advanced mathematics and science courses reflect the gender balance of the school?

- Do boys and girls participate equally in classroom discussions?

- Do boys and girls participate equally in hands-on activities in settings such as science laboratories and computer classes?

- Do girls get into trouble for the same reasons as boys? (For example, are loud voices, speaking out of turn, tardiness, and failure to complete assignments on time, treated uniformly?)

- What proportion of student leadership positions in the school are held by boys and girls?

- Do student clubs, organisations and extra curricular activities seem to attract boys and girls equally? If not, which activities attract boys and which girls? Why?

- Is there gender equity in your school’s sports program? Is the attendance at girls’ events and boys’ events comparable?

- Do teachers, counsellors, and administrators receive training in gender fairness?

- Are there policies for reporting and responding to complaints of sexual harassment and sex discrimination?