Mother Tongue-based Education in Northern Uganda

Country Profile: Uganda

| Population | 36,573,000 (2013) |

|---|---|

| Official Language | English and Swahili |

| Total Expenditure on Education as % of GDP | 2.2% (2013) |

| Access to Primary Education – Total Net Intake Rate (NIR) | 93.65% (2013) |

| Youth Literacy Rate (15-24 years) |

|

| Adult Literacy Rate (15 years and over, 1995-2004) |

|

| Sources |

Programme Overview

| Programme Title | Mother Tongue-based Education in Northern Uganda |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | Literacy and Adult Basic Education (LABE) |

| Language of Instruction | Acholi, Kakwa, Aringa, Madi and Lugbara |

| Funding | Oxfam Novib, Comic Relief (UK) and Africa Educational Trust (AET). |

| Programme Partners | The National Curriculum Development Centre, the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sport, six district education departments, five area language boards, primary teachers’ colleges, parents and 120 schools from six districts of northern Uganda. |

| Annual Programme Costs | US $362,452 (2014). Annual programme cost per learner: US $9.91 (2014) |

| Date of Inception | 2009 |

Country Context

Although English and Swahili are its official languages, Uganda is a multi-lingual country, with around forty local languages spoken. The Government of Uganda has sought, through a series of policies, to promote local languages in education. Article 6 of Uganda’s Constitution (2005), for example, says that ‘any language may be used as a medium of instruction in schools or other educational institutions’. The government White Paper on Education for National Integration and Development (1992) states that local languages should be used as the medium of instruction in all education programmes up to Grade 4 of primary school. However, inadequate resources and ineffective implementation strategies have hampered efforts to put these policies into practice. This is especially true of northern Uganda where decades of civil war (since early 1980s), and their aftermath, have limited the impact education work has had on children, young people and adults. Moreover, existing education policies on the teaching and learning of local languages tends only to focus on formal education up to Grade 4. Thus, there are few opportunities for young people and adults, who have not received formal education and are unable to read or write in their native language, to build up literacy skills in their mother tongue through non-formal or informal education.

Literacy and Adult Basic Education (LABE) is a Ugandan non-governmental organization (NGO) established in 1989 at Makerere University. It has contributed to government efforts in northern Uganda by implementing an education programme that focuses on local languages. LABE’s mission is to promote literacy practices among local community members (particularly women and children) and increase their access to information by enhancing their literacy skills in their mother tongue. In this way, participants become able to more effectively advocate and realize their rights and those of their communities. LABE has expanded its focus to include basic education for children, as well as for adults.

LABE is governed by a board of directors, with members drawn from the Uganda National Commission for UNESCO, institutions of higher education, international organizations, the private sector and a grassroots women’s organization. The members bring with them professional experience in academia, finance, monitoring and evaluation, project planning and NGO management. The secretariat, which is responsible for overall coordination, resource mobilization, monitoring and national-level advocacy, is led by the executive director supported by the senior management team.

Programme Overview

LABE’s Mother Tongue-based Education (MTE) programme operates in six post-conflict districts of northern Uganda: Adjumani, Arua, Gulu, Koboko, Nwoya and Yumbe. Five local languages (Acholi, Kakwa, Aringa, Madi, Lugbara) are spoken across the six districts.

Aims and Objectives

The main goal of MTE is to strengthen the status and use of local languages in marginalized Ugandan communities. Ultimately, MTE is expected to contribute to rebuilding these post-conflict communities. Its three main aims are to:

- Enhance local language-based early-years instruction and bilingual education (mother tongue and English), thereby contributing to improved enrolment, retention and learning outcomes. This objective is achieved mainly through supporting teachers who provide effective instruction in children’s local languages.

- Bridge the gap between home and school by providing parents and community members with adult literacy programmes in their mother tongues, and by engaging children and their parents together in interactive after-school learning activities.

- Integrate LABE’s in-service teacher development and parenting education approaches into the national system for teacher training. This involves LABE’s continuous engagement with the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC).

Target Groups

Due to its broad formal and non-formal two-track approach to mother tongue- based teaching and learning, the programme targets a wide range of stakeholders. Direct target groups include primary school children between Grade 1 to Grade 3 (P1–P3), parents and relatives of these children, and teachers of P1–P3. Head teachers from all project schools are also targeted for training and awareness meetings, so that they can better support P1–P3 teachers on MTE.

Programme Facilitators

The major facilitators for this programme are community volunteers known as ‘parent educators’ (PEs). They are selected by community members guided by LABE’s selection criteria. Typically, these facilitators are adult relatives of P1–P3 school children, drawn from within the extended family. They are expected to have completed primary-level education and must be able to read and write in their local language.

P1–P3 teachers also play important roles as facilitators, in teaching children in their mother tongues, training PEs and implementing school-based learning activities for children and parents.

Home Learning Centres

Most of the programme’s activities take place in home learning centres (HLCs) in different communities. These learning centres might be a simple grass-thatched shelter or the shade under a tree established as a schools-at-home space within a selected homestead. Affiliated to a nearby primary school, HLCs serve as multi-purpose learning spaces where educational programmes for preschoolers, afterschool learning for in-school children and parenting or family literacy for adults are usually carried out. These centers are equipped with solar lamps to allow extra time at night for parents to learn with their children.

Programme Implementation

Approaches and Methods

The first phase of MTE commenced in 2009 and ended in 2013. The second phase began in 2014 and will end in 2018. During the first phase, LABE engaged in advocacy to promote mother tongue education, capacity building, in-service teacher training, adult literacy programmes for parents, and the development of curricula and teaching resources for local language instruction. This phase included a series of micro-level initiatives:

- Informing communities and parents of the value of educating their children in local languages, through events such as International Mother Language Day.

- Supporting area language boards, government institutions that develop areas' local languages, to produce orthographies.

- Working with teachers and children to produce storybooks, children’s magazines and teaching resources.

- Dissemination of experiences from the districts to education policymakers countrywide.

This micro-level work facilitated the implementation of macro-level policy, especially in the context of using local languages in education.

To increase the programme’s impact, the second (ongoing) phase addresses a number of new objectives, focusing more on consolidating the following areas:

- Building teachers' capacity in delivering courses in local languages, including the use of ICTs to supplement the national training offered by teacher educators (known as coordinating centre tutors).

- Increasing parental support for MTE and integrating parental involvement in national systems for teacher training.

Needs Assessment

Prior to the execution of project work, a thorough needs assessment is conducted to gauge problems and needs. Parents' needs are assessed informally through community sensitization meetings, held at the beginning of the project. At these meetings, LABE shares the project goal and gives an overview of the government’s policies on local language-based education. A list of issues that need to be clarified further to parents and community members is developed at these meetings.

Teachers' needs are determined through ongoing meetings and interviews at school. Teachers attending these meetings often report that they have received little professional training in mother tongue-based instruction. For that reason, LABE, in partnerships with teacher educators from primary teachers' colleges, has developed a training programme focused on mother-tongue based instruction.

Activities

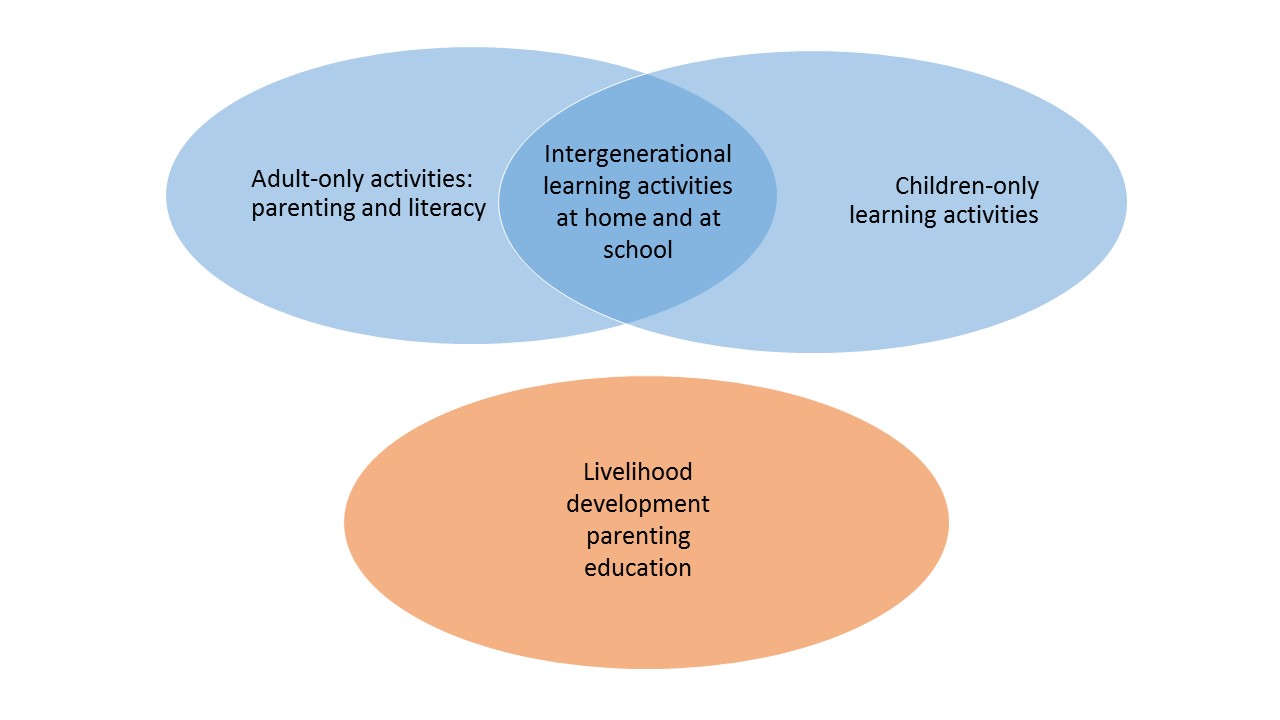

Programmes in blue are offered directly by LABE. The programme in orange is offered by LABE’s partners.

1. Training for Facilitators

P1–P3 Teachers

Mr Dramani, a P3 teacher in one of his literacy lessons in local language

Induction training for in-service P1–P3 teachers was provided in conjunction with centre coordinating tutors, whose main responsibility is to provide primary school teachers with additional in-service professional development. This training lasts for seven days and aims to increase teachers' competence in using the local language as a medium of instruction.

Apart from the formally structured training, P1–P3 teachers are invited to attend teachers' forums, usually held during school holidays or over weekends. At these forums, which are organized by LABE, participants share their experiences of instruction, materials development, advocacy and managing joint parent-child literacy sessions.

Parent Educators

Once recruited, PEs receive initial training of between ten and twelve days to induct them into the programme. This introductory training is followed by continuous training in short sessions conducted by LABE. PEs are trained not only to deliver the parenting course and lead children’s afterschool activities, but also to manage the home learning centre. The training is, for the most part, delivered by P1–P3 teachers.

Parent educators making learning materials for Tetugu HLC

2. Parenting and adult literacy courses and other activities for parents

There are two literacy courses: one integrated with the parenting education course, and one integrated with courses that focus on providing skills to improve learners' livelihoods. Learners can choose to participate in both courses.

The parenting education with adult literacy course targets parents who are unable to support their children’s home-based learning, largely because of their poor literacy skills. Motivated to better support their children’s learning, these parents seek to strengthen their literacy skills. Classes usually take place once or twice a week and last for no more than two hours. There are usually fifteen parents on each literacy training course.

Parents in a literacy class studying the game of “card sorting for Home Literate Environment”

The parenting education with livelihood development course involves adults with and without adequate literary skills in one-to-two hour sessions, twice a week. LABE does not provide the training directly; rather, it partners with other organizations that provide livelihood-related training to parents in LABE’s project areas. For instance, in Koboko district, LABE invited Italian NGO ACAV to deliver agriculture support training in HLCs. In districts such as Gulu and Nwoya, LABE has encouraged some of the parents involved in HLCs to become members of village savings and loans associations, supported by the organizations that offer these loans. Moreover, as a consultancy support, LABE has developed teaching materials for Invisible Children, an organization that provides livelihood-led literacy.

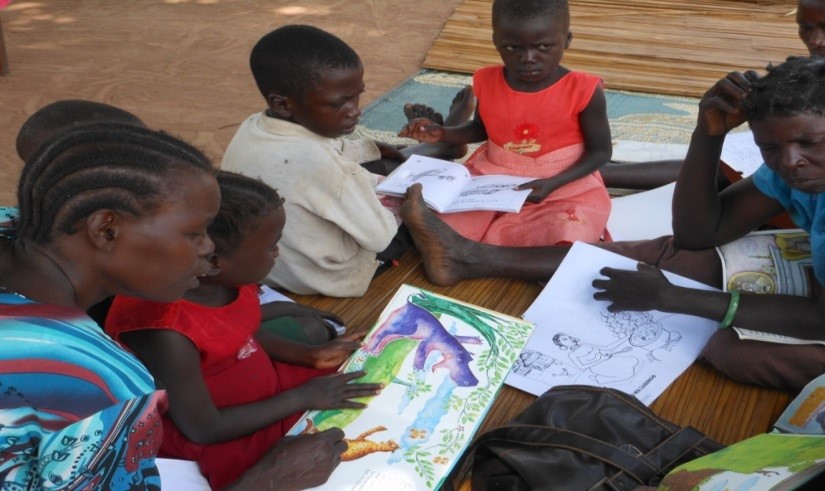

In addition, all parents are encouraged to participate in a weekly intergenerational learning activity with their children at school. This helps parents to participate in their children’s learning and creates a functional home-school link. This activity, managed by teachers with the support of PEs, takes place during the designated literacy hour on the primary school timetable. During the activity, parents sit next to their children in class to encourage them to take part in learning activities such as taking turns to read stories aloud or completing jigsaw puzzles.

Parents and children take part in a school-based intergenerational learning activity.

3. After-school learning activities for children

In addition to engaging in school-based mother-tongue learning activity with their parents, children take part in after-school learning. As an emergent literacy activity, pre-school children (3–5 years) take part in the learning activity. The activity falls into two categories:

- Children-only learning activity: This type of learning activity takes place at least twice a week. Children engage in storytelling, riddling and drawing. It is organized by a parent educator at each HLC. Pre-school children learn how to open books and hold writing materials.

- Home-based intergenerational learning activities: At home, children and their parents read storybooks together or to each other. Parents are also encouraged to help children with learning at home.

Teaching Methodologies

The teaching methodologies applied are specific to each category of learner: parents/family members, children and teachers. In the case of parents or adult learners, a participatory group learning approach is taken. Small group discussions, participatory drawings/visualizations, rankings and traditional folklore are among the techniques used to help adult learners present and share new information and ideas. LABE believes that this methodology enables adult learners to contribute their perspectives, life experiences and ways of communicating to the learning situation.

A whole family learning approach, bringing parents and children together in school-based learning, is used. This method is intended to prepare both pre-school and school-age children for school and increases parental engagement through school-based literacy development. In the HLCs, PEs also use methods of direct instruction, such as read-aloud demonstrations, so that learners are better able to focus in reading new words or numbers. In addition, they use collaborative methods, pair work and games, for example, in completing activities such as jigsaws and picture puzzles. The learning process is engaging to learners, using activities such as storytelling, story acting and traditional folklore.

To make their learning more enjoyable, parents, children and PEs are trained to apply ICT materials, such as digital cameras, camcorders, laptops and mobile phones, in learning and in producing learning materials in their local languages.

The teaching methodology used in training teachers draws on the ‘communities of practice’ approach, which places strong emphasis on mutual understanding and engagement among community members with common goals and interests. LABE has supported the development of networks among teachers so that they can share their experience with each other, as well as developing support materials and facilitating community sensitization, to improve teachers' knowledge of mother tongue-based instruction and their skills in delivering it.

Materials Used and Developed

The learning content for children, teachers and parents is based on the official primary school curriculum for lower grades. However, the project goals, and the particular needs of the target groups, are considered in the development of specific curricula.

A storybag

Learning material is developed by teachers, with technical support from the area language boards. LABE ensures that reading materials are developed in each local language, using authentic knowledge and cultural experiences familiar to the learners. In the first phase of the programme, more than 25,420 copies of storybooks in five local languages were printed and distributed to schools, families and HLCs.

Materials for Parents and PEs

The Parenting Education Resource Book has been developed for parents. It contains worksheets, booklets, charts and posters (such as local language calendars), and guidelines on writing children’s storybooks. PEs use this book as a source of reference and instructional material during parenting education. In addition, family story bags are distributed to each family. These story bags serve as mini-libraries and many families hang their story bag on the wall and use it as a practical tool to store and organize their reading materials. This is a good way of encouraging parents and children to practice their literacy skills at home.

Materials for Children

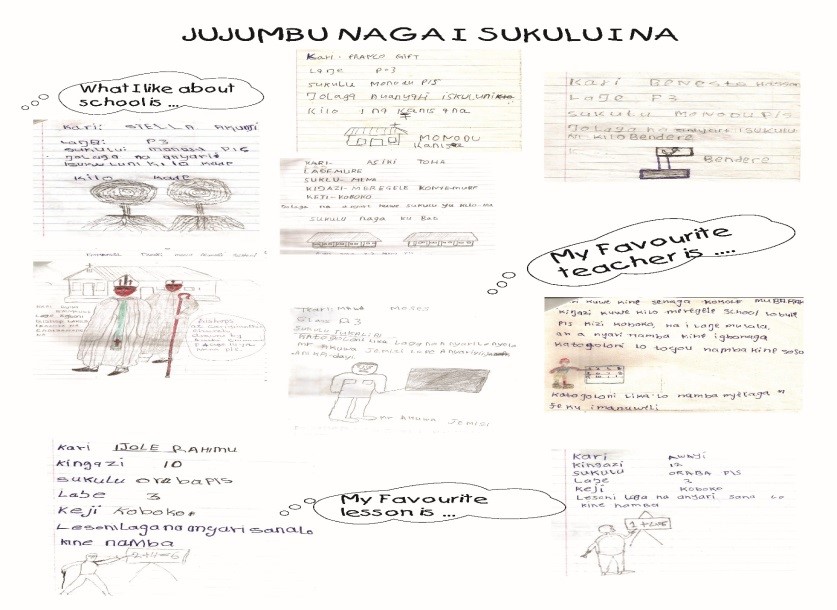

LABE develops storybooks for children in their own local languages. Cards, board games, jigsaws and picture/flash cards are used as materials for children’s learning activities. The children also develop magazines of their own, hand-written in their own style and language. In the first two years of the programme alone, around 16,000 copies of magazines were produced and distributed to project schools and HLCs to be used as learning resources.

A sample of a magazine created by children

Materials for Teachers

LABE and the NCDC has jointly developed The Pedagogy Handbook for Teaching in Local Language, a book currently used in project areas as well as in other parts of Uganda as a national document for in-service teachers to promote and improve the implementation of mother-tongue education. Orthographies of local languages (four of the five have been jointly developed by LABE and the area language boards. These are available for teachers to use in proofreading local language materials. In addition, teachers are trained to produce supplementary teaching materials in local languages, such as syllable cards, work cards and posters, following guidance in the Pedagogy Handbook.

Learning Assessment

Adult Learners/Parents

Adult learners who pursue adult literacy in addition to parenting education are assessed every nine months by the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, which is responsible for monitoring the implementation and quality of the national Functional Adult Literacy (FAL) programme. LABE’s other programme, Family Basic Education, is recognized by the ministry’s 2012–2016 National Action Plan for Adult Literacy as one of the best adult literacy initiatives in Uganda. LABE, therefore, connects parents who attend the parenting and adult literacy course with the district community development departments that oversee FAL, so they can take part in the annual FAL assessments. The learners take a national pen-and-paper literacy assessment in their local language. On passing the test, parents receive a certificate of recognition.

Teachers

Primary teachers trained in the MTE programme are supervised and assessed by their outreach teacher educators as part of their continuing professional development. LABE, therefore, does not directly assess their competencies in mother tongue-based instruction, as it lacks a mandate to do so. However, to complement this traditional assessment approach, which focuses on teachers’ capability deficits, LABE promotes the establishment of professional learning communities among P1–P3 teachers, as an innovative approach to professional development as well as an assessment tool. In this way, teachers co-learn, self-assess and co-assess their professional progress, including capacity in mother tongue as a medium of instruction.

Children

LABE trains PEs to work with parents to assess the school-readiness and transition of pre-school children. PEs and parents use a checklist of indicators, as listed in the Parenting Education Resource Book, to assess their pre-school children’s transition from home to school.

Monitoring and Evaluation

A variety of mechanisms are used to share experiences and good practice among programme stakeholders and within LABE itself. Within LABE, quarterly programme management meetings are held to discuss project progress and any problems arising. LABE programme officers organize regular review meetings and focus group discussions with government partners and community members in order to share report findings and develop action plans.

To be accountable to stakeholders, the wider public, government and civil society, LABE produces periodic publications, such as annual reports. Additionally, mid-term and end-of-project evaluations have been carried out, with reports published and widely shared. These publications highlight the major achievements and challenges of the reporting period and consider how any problems encountered can be addressed.

Table 1: The number of programme beneficiaries and materials developed and distributed.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers | 150 (79 female [F]; 71 male [M]) | 1,190 (555 F; 635 M) | 1,305 (597 F; 708 M) | 1,491 (682 F; 809 M) | 1,491 (682 F; 809 M) |

| Parents | 1543 (11,891 F; 7,438 M) | 19,329 (11,891 F; 7,438 M) | 20,332 (12,427 F; 7860 M) | 21,144 (12,935 F; 8,164 M) | 13,500 (9755 F; 3745 M) |

| Parent educators | 240 (80 F; 160 M) | 720 (278 F; 442 M) | 840 (327 F; 513 M) | 808 (325 F; 48 3M) | 183 (46 F; 137 M) |

| P1–P3 children | 108,000 (53,680 F; 54,320 M) | 156,168 (78,026 F; 78142 M) | 146,584 (73,422 F; 73,162 M) | 141,733 (72,260 F; 69,473 M) | 31,533(16,179 F; 15,354 M) |

| Copies of storybooks distributed | 31,200 | 23,500 | 31,200 | 23,500 | 3,000 |

| Copies of magazines written by children | 2400 | 53,800 | 10,000 | 15,000 | 5,000 |

Impact and Achievements

As Table 1 shows, a number of stakeholders are involved in and benefit from the programme. The programme also develops a variety of learning and teaching materials which are distributed to project areas. It should be noted that numbers decreased in 2014, as LABE phased out of some old project schools in order to focus on fewer programme objectives and activities in the second phase of the programme.

Enrolment of children in primary school grades P1–P3 has increased as a result of learning in local languages. For instance, in just one year of the programme, the enrolment of children in P1–P3 increased by 44.6 per cent across 240 project schools, from 108,000 learners in 2010 to 156,168 learners in 2011. Moreover, schoolchildren involved in the programme have shown greater confidence and improvements in reading and writing in their mother tongue.

The enrolment of parent learners in the parenting and adult literacy courses has also increased, from 1,543 in 2010 to 19,329 in 2011. This is mostly due to the immediate benefits parents gain from literacy classes and the learning process. With their newly gained or improved literacy skills and self-confidence, they have become not only more supportive of their children’s education, but also more active in community activities. For example, parents are now able to write their own names, sign visitors’ books at schools and understand what their children are learning. Some parents, especially mothers, have taken up leadership positions in their communities and introduced new activities, including income generating work, to their literacy groups. Some parents have formed self-help groups so that they can discuss their problems and share skills.

At community level, the programme has bridged the gap between homes and schools, mostly through school-based sessions involving both parents and children. The parents’ own local languages are employed as the medium of instruction in adult literacy courses and the early primary school curriculum, which means they feel more at home in the school environment.

Another significant achievement is the development and publication of two important books: Implementation Strategy for Advocacy of Local Languages in Uganda (2011), and Pedagogy Handbook for Teaching in Local Language (2013). These books are recognized by the NCDC as important resources for promoting change in schools. They are available nationwide.

Testimonies from Adult Learners/Parents/Teachers

‘My life is now better. I can now read and address a public gathering!’ Aate Zubeda, mother and adult learner.

‘I have learned how to read and write my name, I can copy some Acholi words written by our teacher, although I can’t yet read all the comments in my children’s books.’ Florence, mother and adult learner.

‘My attendance at school was so irregular, sometimes I went to school twice in a month and so I could not cope. Eventually I dropped out in P4. It hurt me to leave school and now I concentrate on my literacy class and I actively support all my children to stay in school and finish school.’ Christine, mother and adult learner.

‘I have realized that teaching in local language is interesting because there is full participation from learners and saves time because there is no need for translation unlike in the past.’ Dramani Samuel, P3 teacher.

Challenges

Despite the enactment of policy to make local languages the medium of instruction in Ugandan primary schools, there have been a number of structural and pedagogical challenges to its effective implementation. These include a lack of interest from more advantaged sections of society, negative community perceptions about the use of local languages in instruction, a scarcity of instructional materials in local languages, and inadequate teacher training. According to LABE, resistance to learning in one’s mother tongue is more prevalent among better-educated and wealthier people than it is in rural communities. Because of their political and economic dominance, and their control of print and electronic media, elites can easily influence attitudes toward local languages. The challenge for LABE and its partners is to counter this at grassroots level. Moreover, the power of English in the national education system is well established, with stable financial support from international institutions such as the British Council and the World Bank. It can be difficult to obtain financial support for developing publications in local languages.

Another challenge is to increase the number of parent educators, due to the low stipends offered to them. Sometimes, especially during rainy seasons, the number of participants in the adult literacy programme is quite low, since parents are occupied with farming work.

Lessons Learned

In the first phase of the programme (2009–2013), LABE sought to simultaneously address the ideological, ethno-linguistic and pedagogical aspects of the challenges that hinder the success of MTE. However, LABE has learned that, as an organization, it is important to focus on core issues, while working with others to create deeper impact. Hence, in the second phase, LABE’s main focus is on pedagogical issues, such as lack of language standardization and teachers' capacity development. Ideological aspects, such as public awareness, are best addressed through working with related government partners at national and regional levels.

Another lesson learned concerns the use of oral literature and traditional folklore as an important literacy resource. At the outset of the programme, LABE thought that it would be a challenge to obtain resources for learning materials from communities that lack of written literature. However, it turned out that almost all adult participants in the literacy programme not only possessed a rich knowledge of oral literature and folklore, but also were ready and motivated to share their knowledge. Thus, LABE asked community members to provide more information to participants at local materials-writing workshops.

Sources

- Republic of Uganda. 2005. Constitution of the Republic of Uganda. [Last accessed 25 October 2015] [PDF 311.4 KB]

- UNESCO. 2014. Data Centre Country Profile. [Last accessed 25 October 2015]

- UNESCO. 2015. Family basic education. Learning Families: Intergenerational Approaches to Literacy Teaching and Learning.

- Republic of Uganda. 1992. Government White Paper on Implementation of the Recommendations of the Report of the Education Policy Review Commission, Education for National Integration and Development.

- LABE. 2014. Parenting Education Resource Book. Uganda

- Uganda National Curriculum Development Centre. 2013. Pedagogy Handbook for Teaching in Local Language. [Last accessed 25 October 2015] [5,434.49 KB PDF]

Contact

Ms Stellah Keihangwe Tumwebaze

Executive Director

Literacy and Adult Basic Education

Plot 18, Tagore Crescent, Kamwokya, P.O. Box 16176

Kampala, Uganda

stellah@labeuganda.org

Tel/Fax: +256 414 532116

www.labeuganda.org

Last update: 15 December 2015