Mother and Child Education Programme (MCEP)

Country Profile: Nigeria

| Population | 148,980,000 (2007, UN estimate) |

|---|---|

| Poverty (Population living on less than US$1 per day): | 70.8% (1990-2004) |

| Official Languages | English, Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba and Edo |

| Access to Primary Education – Total Net Intake Rate (NIR) | 72% (2004) |

| Total Youth Literacy Rate (15-24 years) | 84% (1995-2004) |

| Adult Literacy Rate (15 years and over, 1995-2004) |

|

| Sources |

Programme Overview

| Programme Title | Mother and Child Education Programme (MCEP) |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | The Ecumenical Foundation for Africa (EFA) |

| Language of Instruction | English and various African languages of the local area, such as the Ogoni language |

| Programme Partners | River State Government (through the Federal Ministry of Education), UNESCO, private sector (patrons, friends, relatives) and public sector (e.g. the River State Universal Basic Education Board, the River State Adult and Non-Formal Education Agency and the World Bank Fadama lll Project) |

| Date of Inception | 2005 |

Context and Background

Since gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria has made strong efforts to make education more accessible to all citizens. In order to do this, successive national governments have launched various educational and literacy programmes, including compulsory, free Universal Primary Education (UPE, 1976), the National Teachers Institute (NTI, a distance teacher training programme), a ten-year-long mass literacy campaign (from 1982-1992), and the Universal Basic Education programme (UBE, 1999; 2004). The primary goal of these programmes was to promote access to education for all, and they had significant impacts on educational development in the country. For instance, by 2004, access to primary education (i.e. Total Net Intake Rate – NIR) had risen to 72% and, as a result, literacy rates for youth and adults rose to 84% and 69%, respectively, between 1995 and 2004, even though there are variations of literacy rates across Nigeria’s different zones. For instance, the Niger Delta Zone and Northern Nigeria have a higher rate of illiteracy than the southwest region, where free education was introduced by the regional government back in 1962, immediately after independence.

However, a major and indeed persistent weakness of governmental education and literacy programmes has been their failure to provide Early Childhood Education (ECE) and family and community learning opportunities, as well as to make education more accessible to women, particularly those living in socio-economically disadvantaged rural communities. Given that family life is the first literacy environment for every child, the failure to institute broad-based, integrated and intergenerational educational programmes has had a negative impact on the learning performance of Nigerian children. This is not least because most parents (especially mothers) in rural areas find it extremely difficult to be actively involved in their children’s education, due to high illiteracy and poverty rates that are compounded with problems of poor business and a lack of entrepreneurial skills. Furthermore, the lack of family-based education and literacy programmes has also hindered community and family development, and has led to increased migration of young women (ages 18 – 30) to urban areas, most of whom are single mothers leaving behind their young children with relatives or grandparents. Children in rural areas suffer greatly from the deprivation of basic education. Statistics indicate that most children (0 – 6 years) in rural areas have no form of organised learning before primary school, are oftentimes malnourished and are vulnerable to easily transmittable diseases. The situation has improved since the Universal Basic Education Act of 2004, which was enacted to ensure the provision of basic Early Childhood Education, as well as primary and secondary education, across Nigeria. However, there is still a huge gap in access to quality education in rural areas.

This is especially true when issues of information and empowerment are taken into consideration.

Cultural and traditional practices greatly affect the quality of life in some parts of rural Nigeria. For instance, in Ogoni land, which is made up of six local government areas in Rivers State, cultural practice dictates that a family’s first daughter is not allowed to marry even though she is allowed to have children in her parents’ home. Children that grow up in families such as these often face formidable challenges affecting their well-being.

It was against this background that a group of professionals from tertiary institutions established the Ecumenical Foundation for Africa (EFA) in 1999. In 2005, the EFA, with financial support from patrons and friends and technical support from UNESCO, created the Mother and Child Education Programme (MCEP) in Nigeria. The MCEP, a constituent programme within the much broader and holistic Kwawa-Ogoni-UNESCO Educational Development Project (KWUEDP), primarily seeks to make education more accessible to women (mothers) and children and, by extension, to promote women’s empowerment, appropriate child rearing and rural development. The programme therefore compliments existing governmental education and literacy programmes, such as the UBE. It is also a means of assisting the government in fulfilling its international educational and developmental obligations as outlined in, for example, the Bamako Call of Action (2007), the Literacy Initiative for Empowerment (LIFE) goals, the Education For All (EFA) goals and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). To date, the programme is being implemented at about 100 Community Learning Centres (CLCs) across Nigeria’s 23 Local Government Agencies (LGAs) of Rivers State (primarily in Khana, Tai, Gokhana and Degema LGS), Edo and Bayelsa. In total, 5000 women and 300 000 children from across Nigeria have benefitted from the programme since its inception in 2005. The MCEP has been adapted by NGOs and the wives of state government workers, and has developed into a solid best practice example of literacy and life skills programmes in Nigeria.

The Mother and Child Education Programme (MCEP)

The MCEP is an integrated and intergenerational (family-based) educational and literacy programme, sometimes referred to as the ‘civic approach’ to mother and child education. It is ‘civic’ because it is a people-oriented programme, based on the development of a ‘power base’ and ‘voice’ for participants. The programme seeks to make education more accessible to all, but particularly to the vulnerable, poor majority living in disadvantaged and marginalised rural communities. Although the MCEP is an inclusive family and community-based educational programme, it particularly targets mothers and children (ages 0-8 years) who, as noted above, have been marginalised from existing educational and literacy programmes. Therefore, the provision of basic adult literacy and life skills training to women and early childhood education is central to the MCEP.

In order to effectively address the diverse learning needs of women and children from different socio-linguistic backgrounds, the MCEP employs an integrated and bilingual (English and mother tongue) approach to literacy and life skills training. The programme therefore places greater emphasis on subjects and activities that are central to the learners’ socio-economic context and everyday experiences and needs, such as the following:

- Adult literacy and ECE, including mother-to-child education

- Health (e.g. HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention, nutrition and sanitation)

- Civic education (e.g. human rights, conflict resolution and management, peace building, child rearing, leadership, gender and inter-religious relations)

- Environmental management and conservation

- Income generation or livelihood development

- Reading and Democracy: Promotion of reading culture and democratic principles through book and library development

- Rural employment promotion with direct links between mothers and government and International development partners’ projects, such as the World Bank Fadama III project and credit and loan schemes for their small businesses.

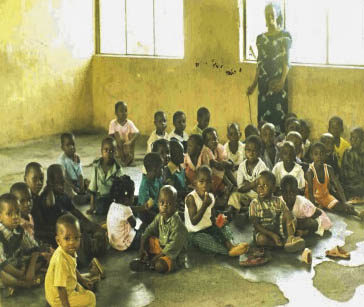

Early Childhood Education

The programme’s ECE component first began as an incentive for mothers to participate in the literacy component. Mothers have often had difficulty finding somewhere for their children to go when they are working at farms or small businesses during the day. This means that children are often left in hazardous environments and, even if they accompany their mothers to the farms, they are often left unattended. The ECE component of the programme provides a space for children to go and also requires the participation of the child’s mother in the literacy programme. Even though the literacy programme is compulsory for mothers, however, they are eager to participate, as they are then exposed to skills’ acquisition, loan and credit schemes or, alternatively, to other government and international development partners projects. The exact amount of empowerment given to mothers through the programme depends on their interests, as well as the available opportunities in the area. The literacy programme is not an end in itself, but serves as the fulcrum for all available opportunities for women to empower themselves.

Programme Objectives

The programme aims to:

- Promote intergenerational (family-based) and bilingual (English and mother tongue) learning

- Provide parents with appropriate child rearing skills, including the supporting role of fathers

- Empower women to participate actively in their children’s education by providing links between home and the literacy centres/schools.

- Equip women groups with the functional or livelihood skills necessary for improving their families’ living standards and access to markets.

- Promote the spirit of volunteerism and self-reliance

- Foster ecumenical principles of equity, justice, peace and social control

- Provide capacity building and training for volunteer teachers, literacy facilitators and women leaders from various projects and members of community development committees for self-reliance of mothers, and an effective local management structure as an exit strategy for the NGO.

Programme Implementation: Approaches and Methodologies

The Role of the Community

The implementation of community-based educational and literacy programmes is often encumbered by a lack of financial and material resources, human resources (professional and/or semi-professional instructors) and, most importantly, community involvement and support. In order to circumvent these challenges and to ensure the success and sustainability of the MCEP, the EFA has prioritised the active involvement of local communities in the development, planning and implementation of the programme. In order to do this, the EFA has organised programme participants into community-based learning groups. Local leaders, primarily chiefs and chairmen of community development committees, have also been lobbied to lend their support to the programme, thus encouraging their people to participate. Traditional leaders, community development committees, and leaders of the learning groups also assist the EFA in developing and designing the programme curriculum, which is often verified by established educational institutions. The curriculum not only addresses the specific existential needs of the local communities, but is also relevant to their cultural systems and traditions. Similarly, the community is also actively involved in the development of teaching-learning materials, which are often made locally. The learning groups are also responsible for establishing and managing Community Learning Centres (CLCs), including ECE centres.

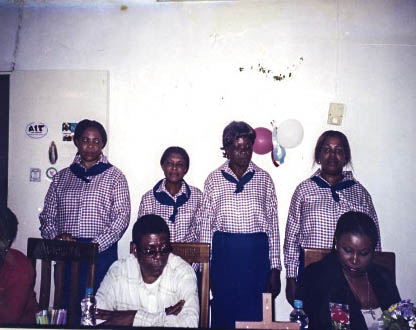

In order to cut programme costs, EFA has also recruited a volunteer cohort of community-based, professional ECE, adult literacy and life skills teachers who are responsible for teaching the programme in their local communities (see pictures below). These professionals are often assisted by semi-professionals, usually young secondary school graduates.

Recruitment and Training of Instructors / Facilitators

As noted above, the implementation of the MCEP is dependent on $50 honorarium payments for a cohort of professional and semi-professional volunteers. However, in order to enable them to carry out their teaching duties effectively and efficiently, EFA provides volunteers with further training and mentoring in the following:

- Adult and child-appropriate teaching-learning methods

- Classroom and mother and child centre management

- Development and production of teaching-learning materials

- Assessment of learning processes and outcomes

- Family mini-library management of resources and books

- Cultural and human rights

- ICT-based ECE and family literacy

The further training provided for instructors and women group leaders is not only intended to ensure the effective implementation of the programme, but also to motivate personnel to participate (i.e. volunteer their services and time) in the programme. Currently, each instructor is allocated about 100 learners, but plans are underway to recruit and train more facilitators in order to bring the instructor-learner ratio down to 1:40. Each instructor or facilitator is paid a monthly stipend of $50.00, which is below the usual amount of $100.00

Recruitment of Learners

Learners are selected according to the community they live in and, due to the acute lack of resources in rural areas, each participating community must have already established a primary school. The community school ensures the availability of classrooms and volunteer teachers for the original implementation of the programme. With the full support of the community, three volunteer teachers is enough to kick-start the literacy part of the programme and, as the centre gradually grows and more volunteer teachers are recruited, other aspects of the programme are established. Families with children (0-6 years) are registered and the initial focus is put on the most vulnerable group in the family: mothers and young children.

Teaching-Learning Approaches and Methods

Training in the MCEP is conducted by volunteer instructors, either at the CLCs (for groups of learners) or through home visits (for face-to-face, mother-to-child training and mentoring). Adult literacy and ECE instructors use participatory teaching-learning methods, including the Participatory Learning and Innovative Approach (PLI) that was adapted from the Centre for Family Literacy at the University of Tennessee, USA, and developed within the framework of a UNESCO module for strengthening capacity through training and technical assistance for volunteer teachers. Typically, adult learners are supposed to complete the MCEP’s core curriculum within one year. However, this period is often extended until learners attain the advanced levels of functional literacy that are necessary for everyday life. This is particularly important for mothers, as they are expected to assist in their children’s educational development – socially, psychologically and financially. Additionally, the period of instruction is often extended to allow participants to balance their learning and livelihood endeavours.

The core curriculum is based on the Federal Ministry of Education New Primary School Curriculum Modules (1 – 6) that were prepared under the auspices of the National Implementation Committee on National Policy on Education, with the assistance of UNESCO. The modules are adapted by the EFA for the MCEP and have also been used by the University of Ibadan Adult Literacy Programme. Modules 1 – 3 are used in the centres since, at the beginning of the programme, most participants have not experienced any form of education and have never had exposure to life outside their communities. Even if they have recently dropped out of school, they are barely able to read and write. A standardised certificate is issued at the end of the programme. In phase II of the programme (2016 – 2020), more advanced literacy modules (4 – 6) will be introduced.

The core curriculum has also been adapted for the MCEP to include additional practical approaches. The level and module for teaching practical approaches depends on whether the class one for volunteer teachers or rather an interactive discussion class for mothers. Approaches are also chosen according local contexts and are designed according to the educational level, interests and cultural background of particular mothers. Literacy classes are taught three days a week (Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2 – 6 pm) and home visits, one-on-one mentoring, dialogues, feedback and consultative meetings are additional aspects that enhance classroom teaching and learning.

The MCEP does not only want to use the core curriculum as a foundation to produce so-called ‘literate people’ who can do nothing more than read and write, which is why they have included a practical aspect. The programme also seeks to have participants exercise creativity and to use their literacy skills to become global citizens.

Programme Impact and Challenges

Monitoring and Evaluation

Programme monitoring and evaluation are central activities in the implementation of the MCEP. Typically, monitoring of the programme and, more specifically, evaluation of the learners’ performance and learning outcomes is undertaken on an on-going basis by both internal (i.e. by EFA staff) and external professionals.

The impact of a programme such as the MCEP is highly dependent on the nature and level of participation. Although the benefits of education are widely recognised, many rural communities in Nigeria have cultural and structural norms that prevent the participation of mothers in the programme. Proper monitoring and evaluation of the programme requires an awareness of factors that promote or hinder participation.

Monitoring Process:

The EFA has two forms of monitoring and evaluation, namely the short- term process for specified activities and the long-term process for overall plans. In the short-term process, the emphasis is on outcome and impact assessment, whereas in the long-term process, the emphasis is on records and assessments, feedback and consultations. Mentorship and local social media are key components of these processes. Local teaching and management personnel carry out assessments, which take place first on a weekly basis, and then later on a monthly basis. The local management structure (which includes M&E; tasks) is made up of volunteer teachers, a representative of the chiefs’ council and the chairman of the Community Development Committee (CDC).

Equity-based Monitoring and Evaluation:

The short-term process is technically referred to as ‘Equity-based Monitoring and Evaluation’. In addition to measuring quality, equity and inclusiveness are also considered. Instead of the usual emphasis on the extent of achievements at the project level, the process includes topics such as how well resources were used, whether activities are carried out within the time frame, what the limitations to effective implementation were, lessons learnt, ways forward and next steps, other issues of ethical standards on the characteristics of beneficiaries. These characteristics include gender, human rights, the nature and availably of tools, environmental factors, mind-sets, levels of vulnerability, feedback, dialogue, consultations and one-on-one mentoring.

Indicators in the assessment are dependent on varying local contexts, making it a bottom-up approach to monitoring and evaluation. Key assessment indicators include the nature and extent of participation. For example, the EFA believes that if only 10% of vulnerable persons in the community are involved in the programme, then in terms of equity and justice, the project cannot be considered very successful.

Despite the investment in education, global reports from UNESCO, UNICEF, UNDP and the World Bank still indicate that the African continent has not had very much success in ensuring equity in education programmes. Equity-based Monitoring and Evaluation is a unique approach that looks explicitly at issues of equality that are perhaps not covered by usual monitoring and evaluation techniques and criteria.

Impact

The MCEP has had a significant impact on overall educational development in rural areas:

- The EFA (with the support of UNESCO and UNICEF) lobbied nursery education (or ECE) to be incorporated into the UBE programme law of 2004. These efforts were successful and ECE, as well as parent education, are now key components of the UBE law of 2004.

- The EFA has supported the River State Universal Basic Education Board in establishing 747 ECE centres in the state’s rural-based community primary schools. This has benefitted about 79000 children in River State alone. However, the cumulative number of child beneficiaries is significantly higher since the campaign to establish an ECE centre at every rural primary school has been and is still being replicated in all of Nigeria’s 36 states (including the Federal Capital Territory).

- Most importantly, the programme has also led to an improvement in the school attendance of children, performance and learning outcomes, not least because mothers have been empowered to participate more actively in their children’s education.

- The provision of literacy and life skills training and the resulting socio-economic empowerment of women has helped to decrease the rate of rural-to-urban migration, a phenomenon that has previously led to inappropriate child rearing practices, as children were often left in the care of grandparents. Furthermore, the empowerment of women through training and support to establish income generating projects has led to sustainable self-reliance and improvements in the living standards of rural families. Women have also been empowered to lead more independent lives, as they no longer rely on others to assist them in activities such as writing letters or opening bank accounts.

- The creation of ECE centres, where children spend the day, also offers the opportunity for mothers to engage in other crucial livelihood activities without disturbance or distraction from their children.

- The MCEP has created invaluable opportunities for community youth to train as literacy facilitators and to earn an income. This has helped to prevent them from engaging in anti-social behaviour out of economic necessity. Others, after working for some time as teaching assistants, have been motivated to pursue further education and training.

Challenges

Although the EFA receives support by various partners, the full and effective implementation of the MCEP is still being hindered by a critical shortage of financial, material and human resources. Initially (2005 – 2008), the programme had full support from the Rivers State Universal Basic Education Board, who provided materials to work with, and local government councils, who paid the volunteer teachers.

Unfortunately, in 2008, the board was dissolved by the current government and the new board does not have the same enthusiasm. Since 2008, apart from technical support and materials provided by UNESCO and partners, the EFA has been under tremendous stress to keep up their originally quick-paced tempo. For instance, because the EFA is only able to pay volunteer facilitators stipends that are far below the poverty line, the programme has struggled to attract more volunteers. Furthermore, financial limitations have also prevented the EFA from providing adequate training to volunteers or establishing more centres across different states. With enough resources and materials from partners, the EFA would be able to cover all viable communities in Rivers, Edo and Bayelsa by 2015, but the challenge lies in finding available resources.

Lessons Learnt

There were some significant lessons learnt from the implementation of the programme:

- It is almost impossible to succeed with any projects in rural Africa without a complete understanding of the social, political, economic, environmental, cultural and spiritual (SPEECS) aspects of rural life. It may take years to acquire indigenous knowledge, but only then can technical expertise and international standards be applied. Once one attains this indigenous knowledge and becomes part of the community life, everything falls into place like jig saw puzzle. The local people will take the project more seriously and become effective partners.

The MCEP was officially launched in 2005, but the EFA has been in these rural communities since 1999 conducting baseline surveys, providing scholarships for skills acquisition for female youth to get placements in local businesses, attending local functions and providing community orientation to the meaning and need for elections and politics. Communities then gradually built confidence and started to believe that they are sincere and are a part of their rural life.

The EFA sometimes carried laptops and made PowerPoint presentations as a way of introducing urban educational life, letting participants know that they themselves can use technology and be part of the academia if they wish. Each programme activity up until 2005 was self-sponsored and sacrifices were made by professional volunteers in order to have communities believe in the project and to see it as something different from existing programmes or their experiences in the past.

- Strong community participation and cooperation is necessary in order to effectively harness local resources. At the beginning of the project, what is most important is the will and power of the people. They must identify with the programme and realise its importance in addressing illiteracy and, subsequently, poverty.

- The project design and planning must be developed in a participatory way, emphasising education and innovation led by target groups, a notion of learning by doing and capacity building at all levels. It is important to pay attention to the interrelatedness of education and economics, which can provide solutions to problems.

- Peace in rural communities and quick conflict resolution is paramount for project success.

- Literacy programmes must have personnel that are adaptive and flexible and that have a lifelong learning perspective.

- The integration of literacy, life skills and ECE learning opportunities is critical for the success of rural-based educational programmes.

- Working alliances with both local and international institutions is critical for the success of any project in rural areas.

- The need to conserve financial resources must be balanced with the need of volunteers to earn an income. Otherwise, professionals and/or semi-professionals will not be motivated to volunteer their time to the programme.

Sustainability

Although the need for strong external support is essential for community-based educational programmes, the sustainability of the MCEP is largely a product of strong and active community participation and ownership. From the beginning, the EFA enlisted the support and participation of entire communities, based on a principle of self-reliance. As such, community members made financial contributions that amounted to the initial necessary capital for the implementation of the programme. Similarly, and despite receiving just a small monthly stipend, community members have also supported the programme as volunteer teachers. Thus, the determination of community members to actively participate in the development activities of their communities and children is the principal driving force of the MCEP. The EFA hopes that all MCEP centres will evolve as community-based organisations in themselves, either at the local or state level, depending on their strengths and capacities. They will teach other and evolve for years to come.

Sources

- The Ecumenical Foundation of Africa: Mother and Child Literacy Development in Duburo Community,(DVD, 2007);

- The Ecumenical Foundation of Africa: The Methodology and impact Assessment of Mother and child Education Programme;

- The Ecumenical Foundation of Africa: Mother and Child Sustainable Education (2008);

- Ahme, J. E, Mother and Child Education: River State UBE Board Book Series 1 – 5.

- Ahme, J,E. (2011) Family Approach to Children’s Education with Economics Dynamics for Quality Assurance

- The Ecumenical Foundation Database on (Female) Youths Literacy & Skills Acquisition Program 2012

- United Nations Agencies: World Declaration of Education for All, Jomtein 1990

- Federal Government of Nigeria UBE Law 2004

Contact

Dr Justina Ahme (International Director)

or

Mr Promise Omachi (Project Coordinator)

The Ecumenical Foundation for Africa (EFA)

P. O/ Box 4565 T/Amadi

D/Line, Port-Harcourt

River State

Nigeria,

Tel: +234 (0) 802 825 4852 or +234(0) 809 993 4007

Email: e_e_ahme@yahoo.com

Last update: August 2013