Literacy and Language Classes in Community Centers

Country Profile: Japan

| Population | 127,368,088 (2011) |

|---|---|

| Poverty (Population living on less than US$1 per day) | 16% (2012) |

| Official Language | Japanese (National language but not official) |

| Total Expenditure on Education as % of GNP | 3.78% (2010) |

| Net Enrolment Ratio (NER) in Primary Education | 102% |

| Adult Literacy Rate (15 years and over, 1995-2004) | Total: 99% |

| Statistical Sources |

|

Programme Overview

| Programme Title | Osaka - Literacy and Language Classes in Community Centers |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | The Osaka Liaison Association in collaboration with local government, educational boards and NGO´s |

| Language of Instruction | Japanese |

| Funding | Voluntary contributions |

| Date of Inception | 1964 |

Context and Background

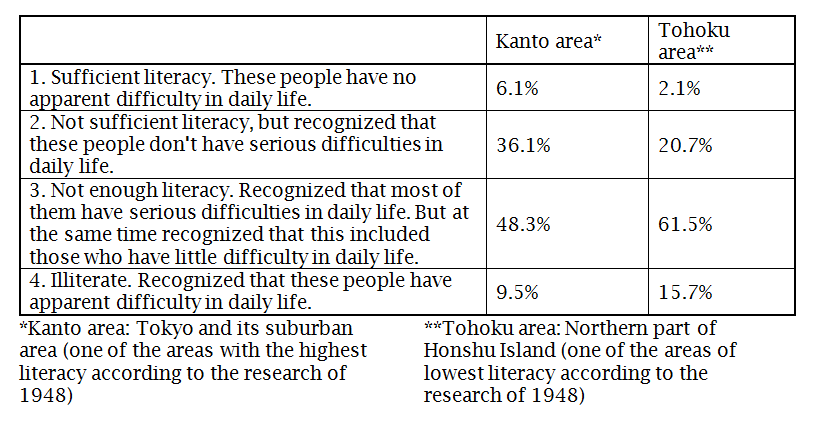

It is difficult to ascertain the extent of literacy in Japan as the country has not conducted a national literacy survey since 1948. In 1955, the Japanese government carried out research on the youth (15-24 years old) literacy rates in two areas in Japan, one in Kanto area, the other in Tohoku area. As these two areas revealed the highest and the lowest literacy rate, it was believed from this they could estimate the entire literacy situation in Japan. According to the research in 1955, at least 9.5% of the youth in Kanto area and 15.7% in Tohoku area are non-literate. It was recognized that these people have difficulty in their daily lives. The Japanese government has not carried out any national survey on literacy since then. This makes the general consensus of 99% adult literacy unconfirmed, especially within the context of low literacy levels among the Burakumin (Buraku) population, which accounts for about 2.5% of all Japanese, constituting the largest minority population in Japan. During much of the group’s existence, they have suffered discrimination from Japanese society. In addition, Ainu are indigenous people in Japan. Most of them live in Hokkaido, the northern island. Most Ainu people in Japan cannot write the Japanese language, due to the lack of governmental support for Ainu’s opportunities in learning literacy. There are also at least 2 million non-Japanese residents (1.57% of Japan´s population), with the largest minorities being Koreans, Chinese, Brazilians, Filipinos and Peruvians. These people often live and work without sufficient Japanese language skills due to the lack of a nation-wide government policy offering adult education. However local governments have gradually been pressured to provide services of some kind, especially for teaching Japanese as a second language.

Due to this, voluntary, non-governmental initiatives organized by citizens have been the main contribution to the development of adult literacy education. These are often run independently and taught by volunteers through literacy learning circles, classes offered by churches, and community centres.

This survey was conducted by the Japanese government in 1955. Those surveyed were the youth aged 15-24 years at that time. This is the last nationwide literacy survey carried out in Japan.

Figure 1. Literacy Levels in 1955 among 15-24 year olds

Osaka and Literacy Classes in Community Centres

Osaka is a major commercial centre and Japan’s third largest city on the main island of Honshu. The city has had a leading role in the creation of adult literacy initiatives due to its history of active literacy participation in the Buraku communities’ literacy movement. The creation of literacy classes in Osaka provides a good example of the implementation of adult education as part of a liberation movement against discrimination. The Osaka Literacy Classes reflect the empowering effect literacy has on a socially disadvantaged community.

The Buraku communities and access to education

´Burakumin´ as a Japanese word initially meant ´village people´. However arising from the Tokugawa era in 1603 was a caste system which created outcast communities of the people originally assigned social functions considered unclean, such as leather workers, executioners, undertakers, butchers, and sewage removers. The Burakumin were forced to work in those areas, often as unpaid labourers, even though their main occupation was as farmers. The Burakumin were officially declared emancipated by the government in 1871, after four years of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. But despite the castes being abolished the system left a lasting imprint on society and the Burakumin continued to be discriminated against.

Due to this the education of the Buraku communities was somewhat marginalized. Large numbers of adults from these communities did not received primary education and consequently could not read or write. This led to the creation of various adult literacy initiatives among the Buraku communities.

The Buraku literacy movement of the 1960´s originated among the communities of a coal mining area where a large number of miners were Buraku. Many mines were closed and workers made redundant. Because of their illiteracy it was almost impossible for them to gain fair compensation with which to support themselves. This caused the perpetuation of a cycle of illiteracy as many children in these communities could not go to school as they instead had to help their families.

Teachers, responding to the high dropout rates at schools, began to investigate and realized it was not only the children, but also the parents, particularly mothers, who were unable to read. From this began a collaboration between teachers and mothers to organize literacy classes in any available space.

Target Groups

The programme is primarily targeted towards adults who did not have the opportunity to complete a school education and achieve literacy. The majority of the students are women, who, due to cultural reasons such as helping with their families and raising children, have had less opportunity to achieve basic literacy.

The evening language schools and literacy classes are also attended by many immigrant workers who have recently arrived and settled in Japan.

There are 35 evening high schools in the country, 11 of which are located in Osaka Prefecture. Besides this, there are about 200 literacy/Japanese language classes in Osaka. Altogether, approximately 6,000 people learn Japanese in Osaka.

Figure 2. Literacy levels (writing) in 2000 among people in Dowa Chiku in Osaka Prefecture

Programme Implementation

In the Japanese language system there are many kinds of letters: two types of Japanese Kana (alphabet-type letters: 50 letters in each Kana system) and over 15 hundred Kanji (Chinese letters) which require a long time to learn in terms of reading and writing in Japanese. Japanese adult literacy education is interesting and unique for its emphasis on reading and writing skills, but also for the necessity of self-expression and interaction through these forms as part of the Buraku liberation movement in particular. The programme lacks a formal structure, and from the program´s inception there were not sufficient facilities or learning materials, so teachers created their own to meet the needs of the learners. Learners can also bring their own study materials that they wish to learn in class. Learning materials are prepared in many different ways depending on each class.

Free learning materials are made available to anyone at the Center for Adult Learning Literacy & Japanese as a Second Language, Osaka,(CALL-JSL,Osaka). Most classes are regularly held in the evening once a week and each class lasts for 1.5-2 hours and continues until literacy is reached. There is no official time-frame for the programme, and students are to decide for themselves as to whether they should continue attending the class. Literacy instructors are often teachers from primary and junior high schools from the local neighborhood for the evening classes, and literacy classes held in other places such as community centers are mostly taught by volunteers. The classes aim to cover basic literacy and numeracy and practical skills such as knitting, with an overall emphasis on imparting values and knowledge of democratic citizenship, and providing the background of the Buraku discrimination and liberation movement.

Literacy classes in Osaka teach language in the context of learners’ everyday lives and encourage expression of experiences and challenges, empowering learners through a deeper understanding of their particular situation and history.

Monitoring and evaluation

There has been no common curriculum in Japanese adult literacy education, so tutors are required to carefully assess learners’ needs before and during teaching by listening to descriptions of their daily life and histories to identify which areas to target. To provide quality services for learners, lectures and workshops for volunteers/instructors working at literacy classrooms are held in many places.

As there is no formal assessment or evaluation, a constant effort is made to ensure the content delivered is directly useful in the lives of the learners, and lesssons aretuition provided until the learner feels his/her skills are sufficient.

There is an annual exchange meeting held where people from different literacy classes can interact. Every year, around 700 people gather to share their experiences of leaning Japanese in literacy classes, giving presentations on their recent accomplishments. There are also collections of essays composed by learners from different classrooms that are made into booklets.

Impact

While updated nationwide statistics are not available, the Board of Education of Osaka Prefecture made its first survey in 1996 on how many literacy classes are being organized in the Osaka prefecture. According to the results, as of March 1996, 292 classes were held with a total number of 3,663 students, including 43 classes in the Buraku areas, 36 classes at community halls, and 22 classes at civic voluntary organizations. The program has impacted primarily women, who constitute 78% of the total number of students. Half of the students are foreign nationals, including Korean residents.

The classes are used to encourage learners in expressing their feelings and life histories. Through sharing experiences and writing about themselves, learners can develop a common empathy. As awareness among Buraku increases they can become stronger as a community, understand the social background of discrimination, and thus resist any continuing discrimination they may experience. According to various personal reports, the style of teaching has significantly empowered the participants, as well as opening up opportunities for them in terms of further education and employability.

Collaboration in Osaka between volunteers, learners and teachers created a network of organisations and individuals active in the field of adult literacy, leading to the ‘Osaka Liason Association’in 1989, the first of its kind. Since its inception the association has been responsible for promoting and linking together the various adult education movements. For example, it requested Osaka city to draw up the first guideline for the promotion of literacy rooted in governmental public policy, achieved in 1993. This was a significant achievement for the adult literacy education movement in Japan.

Through the Buraku people liberation movement which was propelled by their increasing literacy, most classes are now held in public facilities managed by local governments, gaining greater public and political recognition.

The Osaka Liason Association was responsible in 2000 for the recommendation of the creation of a public center of adult literacy and Japanese as a second language. This center now offers multiples services, promoting interaction between different literacy classes; giving information and advice to learners; developing teaching materials and literacy education programs, and training staff for the programmes. This was finalized as the Centre for Adult Learning, Literacy and Japanese as a Second Language (renamed to CALL-JSL, Osaka) which was set up in 2002. This is the first centre of its kind. The programme has stressed the necessity for the Japanese government to implement policies regarding Japanese adult education.

Sustainability

As a mainly volunteer-led organization the crucial factor for its survival is continuing support from local teachers and a demand for the programme. The major threat to the programme’s sustainability is the lack of funding. Furthermore, local governments have still not recognized the significance of the programme, which contributes to the worry that widespread government policies regarding adult education will not be put in place.

Literacy classes in Osaka are facing financial difficulties due to huge budget cuts from the government. Local government is no longer supportive of the programme, despite the fact there is still a demand for learning opportunities and social support through our programme from different minority groups from different backgrounds. Unfortunately, recent budget cuts have put many classes on the verge of closing down. There are ongoing discussions on ways to sustain classes, yet most classes are struggling to find any solution.

Sources

- [DOWA EDUCATION. DOWA EDUCATION. [ONLINE]] (http://www.blhrri.org/blhrri_e/dowaeducation/de_0008.htm)

- Buraku Problem Q & A. Buraku Problem Q & A. [ONLINE]

- Social Education/Adult Education in Japan, 2009, Policies, Practices and Movements during the last 12 years: Analysis and Recommendations, A Report from the Civil Society Organisations to the Sixth International Conference for Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI9)

Contact

Secretary General Sachiko Tamura

HRC building 10th Floor,

4-1-37, Namiyoke, Minatoku,

Osaka City, Osaka

552-0001

Tel/Fax: ++06 6581 8582

Email: User: mb

Host: (at) call-jsl.jp