The Family and Child Education Programme (FACE)

Country Profile: United States of America

| Population | 314,912,000 (2011) |

|---|---|

| Official Language | English |

| Other languages | Spanish |

| Total Expenditure on Education as % of GDP (2010) | 5.6 |

| Access to Primary Education – Total Net Enrolment Rate (NIR) | 96% (2011) |

| Statistical Sources |

Programme Overview

| Programme Title | The Family and Child Education Programme (FACE) |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), National Centre for Family Literacy (NCFL) and Parents as Teachers National Centre (PATNC) |

| Language of Instruction | English, Navajo, and other American Indian languages |

| Date of Inception | 1992 – |

Overview

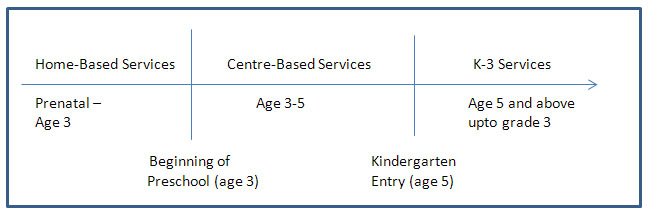

The Family and Child Education (FACE) programme of early childhood/parental involvement was initiated by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) in collaboration with the National Centre for Family Literacy (NCFL) and Parents as Teachers National Centre (PATNC) in 1990. It has over the years been implemented at 54 BIE-funded schools and served more than 10,000 American Indian families with prenatal to grade 3 children by providing adult education, early childhood education and parenting education. Home-based and centre-based services that integrate indigenous/native languages and cultures are offered. The emphasis has been on school readiness and reducing achievement gaps through culturally responsive education, resources and support. Continuing professional development and technical assistance provided by BIE, NCFL and PATNC are crucial elements of FACE.

Context and Background

The National Adult Assessment of Literacy (NAAL) survey in 2003 showed that nearly 14 percent of adults in the USA had low levels of basic prose literacy (ability to search, comprehend and use information from brochures, instruction booklets) and nearly 12 percent displayed low levels of basic document literacy (ability to search, comprehend and use information from job application forms, payroll forms, maps). Studies have shown that the drop-out rate of American Indians is almost twice the national average – the highest compared to all other ethnic groups. The US National Centre for Education Statistics (IES) estimated the national drop-out rate in 2008 to be 8 percent; the drop-out rate for American Indians was estimated to be 14.6 percent. Out of 300 million degrees awarded in 2008 only 3.5 percent and 4.6 percent of Associate’s and Bachelor’s degrees are awarded to American Indians. It was found that 35 percent of American Indians had completed high school but had not enrolled for postsecondary school and nearly 23 percent had dropped out before completing high school. Furthermore, the unemployment rate for American Indians has repeatedly been found to be greater than that of the general population – the American Indian unemployment rate in 2003 was estimated at 15 percent by the IES, 9 percent points more than the general population’s unemployment rate. Research suggests that Children born to parents, especially mothers with less than high school education are much more likely to be found lacking in respect of school readiness (for example, counting to 10, recognition of basic shapes, letter recognition). This also applies to American Indian children, whose Stanford Achievement Test (SAT) 10 scores (standard achievement test in areas of reading, math and science administered through kindergarten to secondary grade levels across schools in the USA) are well below the national average. Furthermore, literacy-related resources, for example children’s books, and literacy-related parent-child interactions (significant predictors of school success) in American Indian families are also not at par with national averages. FACE aims to break this intergenerational cycle of low literacy through its home- and centre-based programmes.

The Family and Child Education Program (FACE)

The BIE, in 1990 developed the early childhood/parental involvement pilot programme based on three distinct early childhood and family education models, namely, National Centre for Family Literacy (NCFL), Parents as Teachers (PAT), and High/Scope preschool curriculum for Early Childhood and the High/Scope Educational Approach for K-3 (kindergarten to grade 3). The programme was implemented in five sites using all three models and the sixth site, known as the ‘single initiative’ used only the High/Scope Preschool and K-3 model. In 1992, the pilot project was renamed as the Family and Child Education (FACE) programme. As a result of its success as experienced in the initial years 48 FACE programmes are now operational in 11 states, mainly on reservations in Arizona and New Mexico (land managed by American Indian Tribes falling under the jurisdiction of tribal councils and not the local or federal government). FACE serves American Indian families in areas of adult, child and parenting education through centre- and/or home-based approaches.

Aims and Objectives

The overall aims of FACE are to:

- Support parents/primary caregivers in their role as their child’s first and most influential teacher.

- Strengthen family-school-community connections.

- Increase parent participation in their children’s learning and expectations for academic achievement.

- Support and celebrate the unique cultural and linguistic diversity of each American Indian community served by the programme.

- Promote lifelong learning.

Implementation: Approaches and Methodologies

FACE Participants

American Indian communities that have a BIE-funded elementary school; are willing to and can arrange to implement all elements of FACE in accordance with programme requirements are eligible to apply for the programme. Participants of FACE are American Indian parents or primary caregivers who have a child prenatal to age 5 (sometimes children upto grade 3). A large number of FACE participants face several socio-economic challenges including unemployment, low levels of formal education and dependence on state/tribal/federal financial assistance.

Home-Based Services

The PATNC provides training and technical assistance for parent educators (mostly American Indian) to deliver FACE home-based services to families with children prenatal to age 3, and sometimes to families with children aged 3-5. Home-based services are provided via Personal Visits, FACE Family Circle, Screening and Resource Network with the primary aim of supporting parents in their role as their child’s first and most influential teacher. Personal visits of one hour are conducted weekly or on alternate weeks and the research-based Born to Learn curriculum (based on principles of child development including (language, intellectual, social-emotional, and motor development) is used to help parents develop effective parent skills by providing culturally relevant learning experiences that support children’s development and interests, and engage parents in developmentally appropriate interactions with their children. Screening and referrals are crucial elements of the personal visits. FACE Family Circle, designed to meet the needs of participating families by addressing child development and parenting issues and by offering families opportunities for social support, is conducted at least once a month. A resource directory is developed by the parent educators and annually updated, which helps connect families with necessary community resources and provides support and advocacy when needed.

Centre-Based Services

NCFL provides training and technical assistance for adult and preschool educators, a large majority of whom are American Indian, to deliver centre-based services to families with children aged 3-5. Centre-based services are comprised of Adult Education, Early Childhood Education, Parent Time, and Parent and Child Together (PACT) Time. Two classrooms, one for 20 children aged 3-5 and the other for 15 adults, in BIE-funded elementary schools are designated for early childhood and adult education classes respectively. The adult education component (2.5 hours per day) aims to enhance parents’ academic, employability and parenting skills using Equipped for the Future Framework and Standards (EFF). The EFF Standards define the knowledge and skills (communication, decision-making, lifelong learning and interpersonal skills) adults need to carry out their roles as parents, family members, citizens, community members, and workers. The High/Scope Approach is used for the early childhood education component (3.5 hours per day) and emphasizes literacy development and children’s involvement in their own learning. Its eight primary content areas are approaches to learning; social and emotional development; physical development and health; language, literacy, and communication; mathematics; creative arts; science and technology; and social studies. The Early Childhood Standards for Math (number words, spatial awareness, symbols, patterns, measuring, counting, patterns, part-whole relationships and data analysis) and language/literacy (comprehension, vocabulary, phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge and concepts about print) are implemented to ensure children’s smooth transition from preschool to kindergarten. During the parent time (1 hour per day) component, parents come together to discuss critical family issues in a supportive environment and to obtain information about various parenting issues. Parents and children are provided with several opportunities to engage in child-directed parent-child interactions during PACT time (1 hour per day) with support and guidance from FACE staff.

K-3 Services

K-3 services are offered via collaborative efforts of FACE and K-3 staff. Though FACE is primarily implemented with preschool children and their parents, there are provisions for parents with K-3 children to participate in centre-based adult education, parent time and K-3 PACT time at the FACE centre. School funds are used to provide appropriate professional development required in order to meet the needs of the K-3 educational programme.

Other Initiatives

- Team Planning Day: In addition to the four days on which direct services are offered to families, one day per week is devoted to meetings for planning, outreach, record keeping, professional development, and/or providing missed services.

- The RealeBooks Project: In 2006, FACE families learnt to create their own RealeBooks on computers using RealeWriter software. Four books are created each month and distributed to all FACE families and kindergartens; posted in an online library and available for FACE staff to download.

- Project ‘Strengthening Our Adult Readers’ (SOAR): Under this initiative adult education teachers are expected, since 2008, to administer diagnostic reading assessments and implement individualized reading strategy instruction in adult literacy classes.

- SpecialQuest Birth-5: In 2009, FACE staff members were introduced to resources and strategies to coordinate with state and local community partners to provide high quality services to children with special needs with a view to insuring inclusion for children with disabilities and their families.

- Read Together – Catch a Dream: Initiated in 2007, this project aims to strengthen dialogic reading strategies used by FACE parents and teachers. Training is initially provided to teachers, who pass it on to parents through special training sessions. Parents are given opportunities to practice with their children new strategies learnt during PACT Time.

- Supporting Family Transitions: Resources, that offer suggestions and tools to help smooth transitions for children from preschool to kindergarten to elementary school and for parents from adult education to the work place, have been developed and provided to FACE staff since 2009.

- FACE Staff Teamwork: In order to enhance teamwork amongst members involved in different components of FACE, BIE sends out a monthly hand-out and quarterly team activities, and provides on-site assistance since 2007.

FACE Staffs and Professional Development

FACE staffs usually consist of five to six members: a coordinator, an adult education teacher, an early childhood teacher and co-teacher, and two parent educators. According to the No Child Left Behind legislation (put into law since 2002 with the aims of ensuring higher student achievement, stronger public schools and a better-prepared teacher workforce across the USA):

- The coordinator is required to be a school principal/school administrator/early childhood education teacher/adult education teacher.

- Home-based parent educators and centre-based early childhood co-teachers are required to have an AA degree (an associate’s degree resulting from a two-year undergraduate course) , 60 hours of college credit or state certification for paraprofessionals.

- Centre-based adult and early childhood education teachers must hold required degrees and be state-certified.

These qualifications are often not visible in schools and communities where FACE is implemented, therefore NCFL and PATNC through the BIE provide high quality professional development and technical assistance such that knowledge, skills and employability of respective staff are enhanced. National Advanced Professional Development and on-site technical assistance sessions are mandatory for all FACE staffs. These aim at helping staff members integrate all delivery components and thereby maintain sustainability. The sessions include training in respect of strengthening the implementation of existing programme components and/or training in implementing new initiatives. Nearly 25 to 33 percent of FACE staffs after 2003 are comprised of previous FACE participants.

Evaluation and Monitoring

Research and Training Associates, Inc. (RTA) were contracted at the inception of FACE to conduct a programme study and to continue to function as an external evaluator. Programme evaluation has served to provide information: a) to ensure continual improvement in programme implementation (overall programme and site specific) and b) about the impact of the programme. Data collection instruments are developed through collaborative efforts of RTA, BIE, NCFL and PATNC. Evaluation reports are prepared based on data (monthly participation and activity reports, implementation data, outcome data, statistical and narrative data) provided by FACE staff members and participants. Annual reports are prepared for the BIE and site-level summaries are provided to individual programmes. Impact and Achievements

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Participation

FACE has witnessed a decrease in the number of home-based participants over the years (from 72 adults and 68 children in 1997 to 39 adults and children in 2009), whereas the number of centre-based adults and children has remained relatively stable over time (approximately 18 adults and 15 children). On average participants remain with FACE for approximately two years, though adults have been found to participate significantly longer than children. This could be attributed to prenatal participation or participation by adults with multiple children. In 2009, similar to previous years, 70 percent participants received home-based services, 24 percent received centre-based services and 4 percent received both. Participation has in large part resulted from parents’ desire to prepare their child better for school. Other reasons cited by parents include the desire to improve their parenting skills, help their child learn to socialize with others, improve their chances to get a job, obtain a GED (General Education Diploma awarded based on the results of five tests to people who do not have a high school diploma; states a person has American or Canadian high school-level academic skills) or high school diploma, or improve their academic skills. Adult participation in all four components of the centre-based services in terms of time is approximately half of the offered time, whereas child participation is close to expectation. While parents have been found to participate fairly intensely in personal visits, regular attendance at Family Circles remains a challenge.

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Adults

- Parents have consistently reported that FACE has helped them improve their parenting skills and understand their child better. Improved parenting skills include more time spent with child, increased involvement in child’s education, more effective interaction with child, increased understanding of child development, enhanced understanding of how to encourage child’s interest in reading, and increased ability to speak up for child.

- In terms of academic ability, pre- and post- measures have shown that FACE has resulted in statistically significant outcomes for adults in respect of reading and math. This finding is supported by parents’ claims that FACE has helped them improve their academic skills for several reasons some of which are achieving higher education and acquiring/improving computer skills. 4,200 adults gained employment during FACE since its inception.

- Programme emphasis on reading and literacy has also resulted in a significant increase in number of adult books and magazines in the homes, and in display of children’s writing/art. A statistically significant increase has also been found in respect of literacy-related activities in the home such as parents providing children more opportunities to look at/read books, scribble, draw and write; listening to children read; telling children stories; discussing the day’s events or special topics with children.

- Other positive outcomes for adults include feeling better about oneself, increased self-discipline, increased interaction with other adults, improved communication skills and increased use of native languages.

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Children

- Early identification of concerns regarding children’s health and development, and obtaining appropriate resources for children are essential to FACE. Programme staffs have over the years provided documentation of screening that has been conducted for children in the areas of language development, fine and gross motor skills, cognitive development, socio-emotional development, hearing, vision, dental health and/or general health. Appropriate action by team members has been taken and referrals to community services have then been made.

- Preschool children have been found to make significant improvements in areas of personal and social development; physical development; the arts; language and literacy; social studies; and scientific and mathematical thinking.

- Parents have reported that FACE has had a large impact in terms of increasing their child’s interest in reading, enhancing their child’s confidence and verbal/communication skills, preparing their child for school, and helping their child get along better with other children.

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Home-School Partnerships

- FACE parents have, over the years, maintained a high level of involvement in their children’s education and the FACE school. Parents’ involvement includes helping with homework, communicating with K-6 teachers about their child, visiting their child’s classroom, attending school or classroom events, volunteering time to provide instructional and/or other assistance at school, and participating on school committees/boards.

- FACE staffs also participate in regular school staff activities (meetings, school-wide planning); and collaborate with classroom teachers, support teachers, and library, computer, physical education, music and art staff. FACE staffs also collaborate with special education teachers, speech therapists, nursing services, and counselling services to better serve FACE children and smoothen their transition to school. Furthermore, formal transition plans are developed and referred to with a view to smoothen children’s transition from home-based FACE to centre-based FACE to kindergarten.

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Community Partnerships

FACE programmes have developed an extensive network of relationships with agencies and programmes that provide basic services such as health services, tribal/BIA social services, community services (alcohol and drug abuse, domestic violence), and county/state services. Partnerships have also been forged with tribal courts/law enforcement, Women, Infants and Children programme (WIC) and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Agency (TANF). In terms of educational services, several FACE programmes are located in communities that have a Workforce Development Program (WDP), a tribal college, post-secondary institutions, BIA adult education programmes, Head Start and Even Start Programs, tribal early intervention programmes, and public preschools/schools. Such partnerships allow for meaningful use of both basic and educational services through two-way referrals. Furthermore, FACE has helped adults increasingly partake in community events and services, for example tribal meetings.

Outcomes from Evaluation Studies: Integration of Culture

American Indian languages and/or culture are well interwoven in FACE programmes. FACE staffs work in close synchrony with schools’ culture teachers in order to integrate language and culture in the programme. Some of the ways in which tribal languages and cultural activities are integrated with FACE services include personal visits conducted using American Indian languages, daily/weekly American Indian language classes, display of cultural artefacts, and organization of cultural events (Native American Week parade, Wild Rice Camp, Indian Day).

Challenges and Lesson Learned

FACE’s efforts at continual improvement are visible in several areas. For example, in 2006, it was found that one book per month provided by the Dolly Parton Imagination library was not enough in terms of easy access to literacy resources in the home, leading to the initiation of the RealeBooks project. Nonetheless, FACE faces considerable challenges in empowering American Indian families living in remote locations. There has been in recent years a substantial decrease in FACE participants as a result of weekly personal visits as opposed to bi-weekly personal visits and emphasis on regular attendance in home- and centre-based programmes respectively. Though incentives to encourage participation are well documented and transparent at most FACE sites, professional development and technical assistance in respect of these need more attention.

Sustainability

Though FACE emphasizes regular attendance, there is also an understanding of the complexities of parents’ day-to-day life and parents are not dismissed from the programme in the light of irregular attendance. Therefore, parents are able to receive basic services on isolated reservations. Professional development and training offered to all staff members play an important role in ensuring sustainability of the success of the FACE model. Networking during these sessions allows sharing of ideas and exchange of information between several programme staffs. Furthermore, on-going partnerships with local- and county-level agencies in the areas of basic/educational services as well as the regular addition of new initiatives to the FACE model also contribute towards ensuring programme sustainability. Conclusion

FACE has made a substantial contribution towards levelling the playing field for high-risk American Indian children and their families. Evidence of empowerment is well documented in annual evaluation reports. Continuous evaluations and revision through feedback need to be continued for enhancement and future success.

Sources

- http://www.faceresources.org/

- http://face.realelibrary.com/index.php/library

- http://www.specialquest.org/about.htm

- BIE Family and Child Education Program (2005). Executive Summary Report prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education.

- BIE Family and Child Education Program (2006). Executive Summary Report prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education.

- BIE Family and Child Education Program (2007). Executive Summary Report prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education.

- BIE Family and Child Education Program (2008). Executive Summary Report prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education.

- BIE Family and Child Education Program (2009). 2009 Report prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education.

- Equipped for the Future (EFF). EFF Fundamentals. Available at: http://eff.cls.utk.edu/fundamentals/default.htm

- High Scope Educational Research Foundation (2011). High Scope Curriculum. Available at: http://www.highscope.org/Content.asp?ContentId=1

- National Assessment of Adult Literacy (2003). Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/naal/

- National Centre for Education Statistics, US Department of Education (IES).Status and Trends in the Education of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/nativetrends/8_outcomes.asp

- Parents as Teachers (2010). Born to Learn Curricula. Available at: <www.ParentsAsTeachers.org>

- Pfannenstiel, J., Yarnell, V. and Seltzer, D. (RTA) (2006). Family and Child Education Program (FACE): Impact Study Report.

Contact

Debbie Lente-Jojola, FACE Program Director/BIE

Ph: 505-563-5258

Email: User: debra.lentejojola

Host: (at) bie.edu

National Center for Family Literacy

Kim Jacobs

Ph: 502-584-1133 Ext. 124

Email: User: kjacobs

Host: (at) famlit.org

Parents As Teachers National Center

Marsha Gebhardt

Ph: 314-432-4330 Ext. 263

Email: User: marsha.gebhardt

Host: (at) parentsasteachers.org