The African diaspora in Asia trade routes and cultural memories

- © DR

The existence of Afro-Asian communities in various parts of Asia, separated by vast distances from each other, speaking a variety of Asian languages gripped my interest some years ago. Why is African migration eastwards barely recognised? How long has this movement gone on for? From where exactly did they originate? These are some of the questions that I asked myself when I came across the Afro-Sri Lankan community, a few miles inland from the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka. At that time, I was researching Indo-Portuguese of Ceylon (or Sri Lanka Portuguese Creole) and the elders still speak this creolised form of Portuguese which was predicted to have died out more than a century ago but has survived against all odds. The others sing Indo-Portuguese songs in which the vestiges of a dying language are embedded.

Acculturation, adaptation and economic pressures have transformed Afro-Asians, but perhaps not surprisingly, their African roots are encapsulated in their musical traditions and dance forms. Music and dance draw them apart from other ethnic groups on the island. Whilst there has been sufficient in-marriage to retain an African phenotype, out-marriage is the norm. They themselves predict that their talents in music and dance will be an identifier of African ancestry even after their physiognomical characteristics have been diluted out.

Many Afro-Asians are hidden in the villages, forests or on the margins of society. Those in the cosmopolitan cities are taken for African tourists and Asians are surprised to hear them speak in the local tongues! Why has the African presence in Asia gone unnoticed for so long? Perhaps the extent of their assimilation and acculturation have contributed to their hidden presence.

It is difficult to get reliable counts of numbers and only estimates are available. Although their presence is not widely known, there is not an insignificant number of Asians of African descent. For example, in India over 60,000 Sidis (as they are mostly called nowadays) live in several states: 25,000 in Gujarat, 25,000 in Karnataka and 10,000 in Andhra Pradesh and smaller numbers in Maharashtra, Goa, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. In Pakistan, where they are known as Shidees, they live in the Sindh and Karachi.

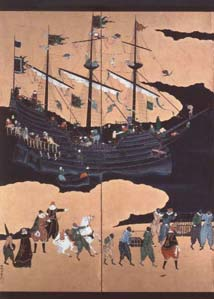

Whilst recognising that free movement of Africans was natural, particularly for maritime seafaring communities, I wondered how far east they had moved. The demands of long-distance international maritime trade and colonisation necessitated sailors, soldiers, servants and the already established slave trade provided a mechanism for obtaining the required manpower. Not surprisingly, Portuguese ships that sailed to Macau and Nagasaki included Africans.

Whilst socio-religious practices were a push factor in early African movement, economic pressures and commerce contributed further. The Dutch, the French and the British who followed the Portuguese into the Indian Ocean also included Africans in their Asian enterprises. Various streams of migration have resulted in today’s Afro-Asian communities. Where numbers were small or influenced by socio-religious factors, some migrants were absorbed into Asia. Others have disappeared from the historical record as they were not important enough to be visible.

Having an interest in cultural maintenance and transformation, I began to search for the roots of Afro-Asians. They were not homogeneous as their ancestors had originated from Mozambique, Madagascar, Angola, Tanzania, Zanzibar and Ethiopia, for example. They spoke many African languages but as many migrants were East Africans, some Sidis can also speak a few sentences of Swahili. National Archives and the British Library records testify to the recruitment of slaves as soldiers and for other tasks, to run the overseas operations and to fuel the imperial machinery.

With increase of migration, diaspora studies have become an integral part of global history. My latest book - The African Diaspora in Asian Trade Routes and Cultural Memories contributes to building a more comprehensive narrative of the global African movement. Predominantly concerned with the easterly movement of Africans to Asia, this book includes contrasting case studies from Sumatra and Sri Lanka, based on East India Company records in the British Library (London) and fieldwork in Sri Lanka. Whilst searching for the origins of Africans taken to Bencoolen (Sumatra), I uncovered a slave route from Madagascar to Sumatra and Java via India and Sri Lanka. I identified origins of slaves - Mozambique, Madagascar, Angola. The records also revealed the haphazard nature of abolition in the Indian Ocean, an area which calls for further studies. Africans played a vital role as interpreters, musicians and facilitators of cultural transformation. I have therefore theorised on how Africans themselves were affected by the process of migration.

Eastwards migration in the Indian Ocean region and beyond, has gone on for longer than the westward migration across the Atlantic and the geographical spread is wide. Africans moved eastwards over land and by sea. Although scholarship on the eastwards diaspora has increased over the last decade or so, there are still many roots and routes to uncover.

- Author(s):Dr Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya (Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London & Member of the UNESCO International Scientific Committee of the Slave Route Project, Paris)

- Source:Royal African Society

- 24-06-2011