Bordered to the northwest by the United Arab Emirates, to the west by Saudi Arabia, and to the southwest by Yemen, and sharing marine borders with Iran and Pakistan, the Sultanate of Oman occupies the whole southeastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a country of vast spaces and stark contrasts, its boundaries defined by nature at its most extreme and frequently its most majestic. Its 1,700 km coastline overlooks the Sea of Oman and the Persian Gulf, known in ancient times as the Erythraean Sea, and protects an interior that rises from flat coastal plains to a central massif averaging 1,500m above sea level and reaching at its highest the 3,000m peak of Jebel Al-Akhdhar. Further inland, the mountains fall away to the west, descending into a desert which merges with the Rub’ Al-Khali, or Empty Quarter, of Saudi Arabia.

Separated from the main land mass of the Sultanate by the United Arab Emirates is the Omani enclave of Musandam on the Strait of Hormuz, the strategic narrow passage through which the waters of the Persian Gulf empty into the Sea of Oman on their way to the Indian Ocean. The Strait is one of the world’s most strategically important choke points, with upwards of 35% of all seaborne petroleum trade passing through the 29 nautical miles of its narrowest point, using one-way shipping lanes two miles wide in each direction with a 2-mile-wide median.

From the country’s central massif, seasonal waters pour down onto the green plains below along steep gorges, and since ancient times Omanis have harvested these waters and channelled them through intricate manmade aflaj or water channels to support plantations of date, banana and coconut palm, as well as a variety of grains, fruits and vegetables. Along the coast, fishing has been an important source of sustenance and revenue from the time of the earliest human settlement in Oman, identified at Wattia near present day Muscat and dating to the 10th millennium BC.

Fishing would have provided the initial impulse for the growth of the seafaring tradition for which the Omanis became justifiably famous over time; along with a natural and open curiosity for faraway lands and cultures that fuelled the growth of its shipbuilding industry and, ultimately, mastery of Indian Ocean trade as far as India, China and East Africa. From the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea it is known that vessels from the distant port of ‘Omana’ (possibly ancient Sohar or Muscat) had reached the southern shores of China. Even earlier, Agatharchides, who lived in Egypt in 120 BC, wrote that the “Omanis have arrived on the Indian coast.” At this time Oman’s merchant fleet was already one of, if not the, strongest and largest in the world.

THE MARITIME ROUTES

East to China

Omani sailors had a reputation for bravery in facing the mountainous seas and other terrors of ocean-going travel and had an unrivalled knowledge of seasonal weather patterns, as well as of astronomy and the art of navigation. They are thought to have pioneered the use of mast and sail. The great 10th C Arab traveller Al-Mas’udi, the ‘Herodotus of the Arabs’ who made long voyages with Omani merchants, reported that on the 8,000 miles of ocean between Abyssinia and India and China, “most of the mariners are from Oman.”

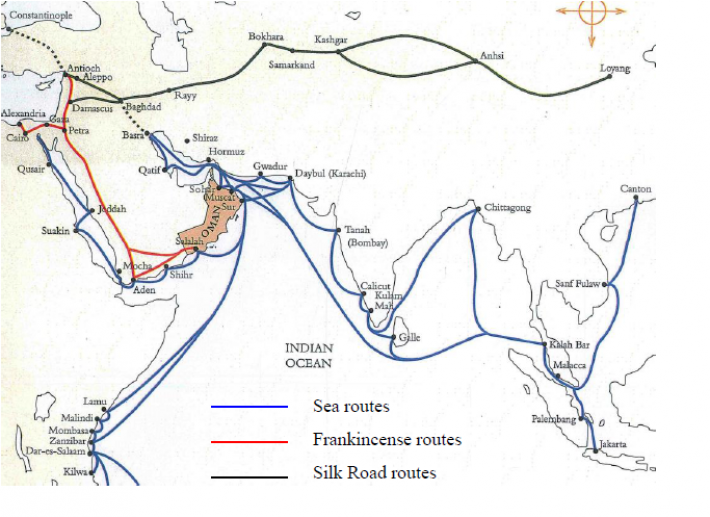

Although the northern overland Silk Roads from China to the Mediterranean was safer and shorter than its alternative by sea, the vast experience of Omani navigators and merchants gave them exceptional access to the Indian Ocean maritime route. This enabled them to supplement their trading exchanges with the products of the Indian subcontinent and the Persian Gulf on a single voyage. The route was described in some detail by the Persian geographers Ibn Kordadabeh and Ibn Faqih.

The journey from Muscat to Kolham Mele on the southern coast of India took approximately a month, after which the ships sailed on to Serendib (Sri Lanka), and then crossed the Bay of Bengal to the Andaman Islands. A further ten days at sea took them to Bitoma to take on drinking water, thence to the Strait of Silahit (today’s Strait of Malacca), and finally to Canton, where Omani sailors were known for their happy songs of safe arrival in Chinese waters. Canton, Al-Mas’udi wrote, “is a great city located on a river. Merchants’ ships heading from Oman enter this river.” At the zenith of the T’ang era (619-907 AD) records note that there were over 1,000 Arabs and Muslims in Yangzhou, focused on the trade in silk, jewels and corundum, and 10,000 in Guangzhou (Canton).

A side branch of the main Indian Ocean route ran from the Andaman Islands to Java. An additional navigational route linked the Persian Gulf directly with the Sind (Pakistan).

These journeys were fraught with political as well as navigational dangers, and were frequently adapted to cope with onshore turmoil. Al-Mas’udi describes how, in the latter days of the T’ang Dynasty, upheavals in China led Arab and Chinese traders to meet for an exchange of goods at the Andaman Islands, the halfway point between China and Oman. Over time the Omanis developed these islands into important trading centres for goods such as gold, silver, silk, cotton, textiles, Chinese money, incense, sandalwood, ivory, coral, pearl, perfume, minerals, land and sea turtle shells, musical instruments, ebony, cotton and timbers. This reached a point where at the end of the 10th century the Chinese Emperor had to send a high-ranking delegation to persuade traders to return to China.

With trade and diplomatic relations fully restored under the Sung Dynasty, the Arabs and Chinese developed a new trading route:

“From Guangzhou one started sailing on this new route around November, and after forty days of sailing, arrived at Aceh in Sumatra in order to prepare and start for the long journey which will cover two months. Along this journey, the ships were sailed across the Indian Ocean to Dhofar then to Aden, after which the traders have got goods and commodities from the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and Africa during the summer. They worked out how to avoid tropical storms by heading towards the south, taking curved sea routes to Sumatra, and returned to China in the month of August or September.”

Sumatra was mentioned in the 8th century (as Al-Rami) by Al-Himyari as one of the most important stations on the curved East-West sea route, which transited Serendib (Sri Lanka) to take on spices and minerals.

At the other end of the voyage, in Oman itself, was Sohar, of which Al-Muqadassi wrote in the 10th century that there was “no town on the China Sea today that is more important, more populated and prosperous than Sohar”. It was the most mentioned port in Chinese records and became known as the ‘gateway to China.’ Merchant ships bound for China embarked from this prominent port city, after assembling cargoes from smaller vessels in the Gulf as far as Basra to the north. On the return journey, goods unloaded at Basra travelled by overland caravanserai to a junction with the land caravans from the East at the ports of the Mediterranean, and thence to Europe. From the great storehouses of Sohar, meanwhile, goods destined for Europe or Africa made onward journeys overland to join the great Arabian caravans heading northwest to Red Sea ports, or by sea to the East African coast.

Almost a millennium before Sohar’s heyday, the Periplus made references to Oman’s Masirah Island, Qalhat and the Jebel Al-Akhdhar in its description of how silk was transported overland to east India and then to northwest and south west India by sea. This predated the opening of the sea route to China by Omani navigators.

West to Africa and Europe

Sohar was also the starting point for the main trading route from Oman to East Africa, and link port, along with Muscat, for a major exchange of goods between East and West. The maritime route hugged the coastline to Mahra and Shihr (Hadramaut) and then Aden, before setting a course due southwest. Merchant ships stopped off at the island of Socotra to take aboard aloes, before sailing onwards to the East African coast, travelling with the monsoon winds. Safala in Mozambique was the furthest southerly extent of this perilous voyage to the four geographical regions known to Omani sailors as Berbera (Abyssinia), Zinj, Safala and Waq Waq. Along the 500 mile long stretch of Berbery Bay, the ships, divested by now of their original cargoes, called at Hafuni (Hafun in northeastern Somalia) and Bandar Moussa before anchoring at Mogadishu, “the celebrated Islamic city of the Bilad al-Zinj region mentioned frequently by travellers” (Al-Maghrabi). The stretch of coastline from Mogadishu to Safala, defining the Bilad al-Zinj, was where the bulk of the commodities sought by Omani merchants lay and Mogadishu was still a thriving city in the 14th C when Ibn Battuta described its citizens as “powerful merchants always ready to welcome incoming vessels and to take what goods they had aboard.” No more than a day’s journey from Mogadishu were Marka and Birawa; and the next ports of call were Patta and Lamu in the Lamu Archipelago; then Malindi and Mombasa, where an exchange of goods would take place.

Through the Zanzibar canal, the ships made for the island of Zanzibar, which was known intimately to Omani sailors, according to Ibn Majed, along with its surrounding waters, nearby islands and natural geography. Although scholarly opinions differ, it is believed by at least some that Zanzibar was the mysterious island of Qanbaloo much cited by mediaeval geographers and travellers.

From Zanzibar Omani ships sailed onwards to Kilwa, a thriving ivory port some 300 km south of Dar Es Salaam in present-day Tanzania, and then on to the final stretch of their journey - to Safala, Al-Idrisi’s “land of gold and ore.” Here, the ships took on as much gold as they could carry for the return journey. The great Omani navigator Ibn Majed, who composed the celebrated ‘Poem of Safala’ in honour of the district, described the gold mines of Safala as a month’s journey due west in a region submerged in water, or a march of seven days.

The winter passage from Oman to East Africa took three to four weeks, although the voyages were extended by the port visits. The return journey was accomplished in summer, supported by the prevailing southwesterly winds, for which they waited up to two months, making for a total return trip of six to eight months. Tidal factors, swells, depths and rains all had to be taken into account in breaking the journey into stages and skilled Omani sea captains, oarsmen and navigators were in great demand by the merchant trade, most often in the employ of their own countrymen.

If we consider also the maritime Spice Routes which predated the Silk Routes, along with the Arab-dominated Incense Routes, all of which parted, crossed and merged on their long journeys, the Red Sea brought this precious cargo from round the tip of the Arabian Peninsula northwards on the Red Sea to Egypt’s eastern ports, overland to the Nile, and thence to Alexandria for shipment to Rome and Constantinople. Alternatively, overland caravans crossed the Arabian Peninsula diagonally from Oman or north from Yemen, converging at major trading centres such as Petra, then on to Gaza or north to Damascus and Palmyra.

OMAN’S CULTURAL INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER DESTINATIONS ALONG THE SILK ROUTES

The trade routes constituted a vast communications network that transmitted far more than tradeable commodities. They carried ideas, creeds, fashions, customs and languages from one extremity to the other, much as the internet does today. South Arabians taught the Indians astronomy, philosophy, maths and astrology several centuries before the dawn of the Hellenistic Era. The great Omani mariners Ahmed Ibn Majed and Suleiman Al-Mahri studied the science of navigation and then transmitted these principles, enriched by their encyclopaedic practical knowledge of the Indian Ocean, to generations of mariners and sea captains around the world. Most significantly, Omani merchants were greatly responsible for the spread of Islam.

Islam

Oman was one of the earliest communities to adopt Islam, in the lifetime of the Prophet Mohamed himself, and went on to carry the tolerant, peaceful message of Ibadhi Islam wherever its trading interests or cultural curiosity lured it. Omani merchants introduced Islam to East Africa, to the Malaysian archipelago, the Indian sub-continent and beyond.

When Basra was a hub of early Islamic learning in the first century of the Hejira, Omani scholars were among its leading lights in the generation of new ideas and then communication of these to the expanding Islamic world. Wisdom they likened to “a bird, who laid her eggs in Medina, hatched them in Basra and flew to Oman.” The list of Omani authors at this time was rich, and the Omani Library accumulated an unrivalled collection of works in Islamic jurisprudence, history, literature and other disciplines. This product of ‘internal exploration’ their compatriots took with them on their maritime explorations abroad.

The celebrated Omani frankincense merchant Al-Qassim, later joined by another prominent Omani businessman, Al-Nadhar bin Maymoun, settled in China in the second century of the Hejira, where they married Chinese women, raised families and erected mosques in Chinese cities, including the Grand Mosque in Guang Zhou, which dates probably to 1009 AD.

An Omani expedition led by Hashim bin Abdullah and cited in Chinese sources, notes that he brought gifts including pearls, dates, rosewater and textiles to the Chinese emperor. A subsequent voyage by Abdullah led him to stay for several years in Canton where, being close to the Emperor Shen Zong, he was appointed as mayor of the foreigners’ district in the city. He returned to Oman in 1072. These and others like them contributed greatly to the spread of Islam in China. Muslim traders saw themselves as both merchants and teachers.

Islam had the most profound impact on the lives of those who adopted it, from the manner of worship, to male and female dress, to public behaviour, marriage and family, inheritance, the treatment of women, orphans and of followers of other religions who came under Muslim rule.

Scholarship

Probably the most significant Omani scholar of this time period was Al-Khalil bin Ahmed Al-Omani, who pioneered the study of prosody and poetic metre and became the premier teacher of language in Iraq. Of his successor, Ibn Durayed, who grew up in Oman and divided his time between Basra, Persia and Baghdad, and who was known as “scientist of the poets and poet of the scientists”, it was said that when he died “the science of language died with him.” The 9th century Al-Mubarrad, another Omani émigré to Iraq, outstripped all of his peers in grammar and language. These and generations of others upheld a long tradition of Omani scholarship, along with a poetic tradition that predated Islam. All of them travelled vast distances to other centres of learning, particularly to Iraq and Persia, and wrote extensively.

Pacifism

Undoubtedly the most significant product of all of this Omani scholarship was the emergence and dissemination of what became to be known as Ibadhi Islam, which eschewed violence and appealed to the Omani preference for negotiation and pacifism, reflecting the true spirit of Islam. Ibadhism flourished in Oman and in North Africa and contact was maintained between mashraq and maghreb over the centuries, sometimes despite suppression by the ruling powers. The key to spreading the message of Islam, according to its leader Abu Ubaidah, was to repudiate difference and embrace unity, and to cultivate reticence when rivalry was present, a philosophy he told his followers that he had learned from personal experience. Ibadhism is still Oman’s preferential interpretation of Islam, informing its interactions with others at every level, culturally, socially and politically.

Trade

The Islamic Era was a time of great flowering for Oman, ruled by peaceful and devout leaders who welcomed all visitors to its shores and offered safe harbour, sweet water and transit facilities to mariners.

The very extent of the distances covered by Omani merchants, and their reputation for diplomacy, piety and integrity, gave them an edge in negotiating trade agreements, in interacting with other cultures and extending their influence.

Oman exported horses in great quantities to India, pearls and ambergris to Africa, along with dates, copper and, of course, frankincense. In addition, it prospered from the trade in spices from India and Serendib by way of its own entrepot ports and overland caravans across the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean. Merchants also traded cotton, gold, silver, perfumes, gemstones, ivory and ebony from India and the Andaman Islands, and silk, musk, clay and sable from China.

From East Africa, they shipped ivory to China for use in the carving of chess pieces and other ornaments, and imported ebony, teak and sandalwood for their own thriving shipbuilding industry. Chinese references record that rhinoceros horns were imported to China from various parts of Asia, but that the finest quality of all were those brought by Omani tradesmen from Zanzibar.

Travel, pilgrimage and language

Trading objectives spawned the emergence of the travelling geographer, historian and observer of human life and culture, who most often followed merchant or pilgrim routes or accompanied merchants on their voyages. These intrepid men, through their written chronicles, supported the spread of knowledge far and wide and fed such literary masterpieces as the Thousand and One Nights, in which Sindbad, who may have been a real person, set sail from fabled Sohar. Many of these travellers visited Oman and experienced its hospitality, including Ibn Mujawir, Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. Islam, meanwhile, was fuelling great movements of devout pilgrims, who travelled in caravans across desert and ocean to reach Mecca. On one such caravan from North Africa 300 male births were recorded, along with an undefined number of female births and uncompleted pregnancies.

On all of these journeys, ideas and customs were exchanged across tribal lands and settlements. Precious commodities, such as Omani frankincense and pearls, smoothed diplomatic introductions.

Some of the commodities had a transformative impact on life, such as the spices that revolutionised diets and health, or the Omani horses that supplied the armies of Delhi, about which Marco Polo noted that one Hindu king and his brothers each imported 2,000 horses a year from Oman, at a cost of 500 marks of silver apiece.

The coastal culture of the East African littoral was born of the intercourse of Bantu Africans and the Arab and Persian traders who visited its shores and often intermarried and settled there. The Swahili (from the Arabic word for coast) language, today the most widely spoken language of East Africa, is deeply infused with Arabic vocabulary. Omani links with Zanzibar, always particularly close, were fully formalised when Zanzibar became the seat of the Omani royal court in 1698 after the defeat of the Portuguese, extending Oman’s influence deep into Africa, as far as Kindu on the Congo River. Over time, waves of Zanzibaris crossed to Oman and settled there, bringing African traditions with them.

Art and ornamentation

Oman was a thriving country in mediaeval times and its prosperous citizens had direct access to the most exotic of the luxuries arriving at its ports: silk brocades and porcelain, perfumes and precious gemstones found their way into the mansions of Muscat and Sohar. A fashion for classic blue and white Ming chinaware drove soaring demand in the 14th century.

The geometric themes of Islamic art spread west and east along the trade routes, inspiring ceramists, engravers and architects to soaring new heights of creativity and beauty.

Not all such exchanges were appreciated, as Pliny complained: “But the sea of Arabia is still more fortunate; for ‘tis thence it sends us pearls. And at the lowest computation, India and the Seres [China] and that Peninsula together drain our empire of one hundred million of sesterces every year. That is the price that our luxuries and our womankind cost us!”

And again: “Nay, more, they have taken up the notion also of piercing the ears, as if it were too small a matter to wear these gems in necklaces and tiaras, unless holes also were made in the body to insert them in!”

IMPACT OF THE SILK ROADS HISTORY ON THE PRESENT DAY ECONOMY AND CULTURE

After Vasco de Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, the Portuguese occupation of Oman’s ports and aggressive dominance of the Indian Ocean trade brought poverty where there had once been prosperity, putting the seal on an extended era when Oman’s cities were marked by sophistication and culture, by thriving marketplaces, great libraries and splendid mosques.

By the mid-17th century, however, Oman had liberated Muscat and was fast rebuilding its naval fleet, which gradually regained its prominence over the ensuing two centuries. With the rise of the Al Bousaidi State, coinciding with increasing focus by Western imperial powers on the region, Oman could call on many centuries of interaction with disparate cultures, creeds and political systems to demonstrate a gift for diplomacy which since that time has spared it many tribulations and supported its standing as a strong sovereign State, independent, peaceful, respected and respectful of its neighbours and of its own people and environment.

When Sultan Qaboos bin Said succeeded his father as ruler of Oman in 1970, he inherited nevertheless a country that was poor and undeveloped. Over the course of the next 45 years he opened up and diversified the economy of the Sultanate, investing newfound oil wealth in an ambitious infrastructural development plan.

Under the umbrella of the Modern Renaissance, Oman has carefully nurtured its relevance as a trading hub. Among its many ports, Salalah Port in Dhofar is today listed as one of the 20 most pivotal port destinations for container transfer worldwide. Sohar Port still thrives today, having undergone successive expansions. Qalhat specialises in the export of natural gas. And the old port of Muscat, today’s Sultan Qaboos Port, today welcomes cruise liners from all over the world, as Omanis’ long and justified reputation for welcoming strangers turns the Sultanate into a growing tourist destination.

The Sultanate enjoys positive health statistics, a high literacy rate and a thriving economy. Careful planning has ensured that its environment has not suffered the negative effects of untrammelled growth and this moderated approach is reflected in the pristine quality of its natural environment and its wealth of restored heritage sites, several of which are on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Oman’s exceptional social and political stability is reflected in its amicable relations with Arab, Gulf and Asian neighbours, as well as with the major world powers. Its well-equipped navy protects strategic shipping lanes in the Gulf. A history of pacifism and quiet diplomacy, and a refusal to interfere in the internal affairs of others, has earned it outstanding success in the resolution of local and regional disputes, as exemplified by its own peaceful borders. There can be few more fitting tributes to the core purpose of the Silk Roads than the attainment of peaceful relations between nations. In the words of Al-Maqdisi: “By means of the merchandise of China is wisdom spread abroad.”

Under Sultan Qaboos, the Sultanate has maintained an extended close collaboration with UNESCO, and this collaboration includes a three-decade-long commitment to the UNESCO Silk Roads Initiatives. One of the highlights of this commitment was the Maritime Silk Roads Expedition for which His Majesty Sultan Qaboos granted UNESCO the use of his Royal Yacht, the “Fulk Al-Salamah” for over six months (October 1990 to March 1991). On a 154-day, 27,000 km study trip from Venice, Italy to Osaka, Japan, 100 scientists and 45 journalists from 34 countries engaged in an exchange of ideas about the cultural interactions, common heritage and plural identities that emerged and developed along these maritime routes over the centuries. Twenty seven historical ports in 16 countries along the Maritime Silk Roads were visited, most of them old trading grounds of the Omanis themselves. From a nation with such a strong connection with the sea and seafarers, it was an appropriate, and typically generous, gift.

More recently, the Sultanate is again providing political and financial support with a subsidy of US$50,000 for the new initiative “The Silk Roads Online Platform for Dialogue, Diversity and Development”, launched in 2011. This contribution will enable the Online Platform to reach a wider public, particularly in the Arabic-speaking countries, and to disseminate knowledge and scholarship developed by academic and cultural institutions in these countries.