CDIS | Ecuador's indicators

Culture matters in Ecuador: CDIS indicators highlight Ecuador’s culture sector’s potential for economic development and wellbeing, while underlining certain obstacles in place that inhibit it from reaching its full potential.

1019

1 CONTRIBUTION OF CULTURAL ACTIVITIES TO GDP: 4.76% (2010)

In 2010, cultural activities contributed to 4.76% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Ecuador, which indicates that culture is responsible for an important part of national production, and that it helps generate income and sustain the livelihoods of its citizens. 57.4% of this contribution can be attributed to central cultural activities and 42.6% can be attributed to equipment/supporting activities. When examining culture’s contribution to GDP by nationally determined sectors of the economy, the largest share of culture’s contribution falls under the sector of Information and Communication (42.6%), while the second largest share falls under Profesional, Scientific and Technical Activities (20.8%), which includes advertising, design, and architecture activities. Culture’s overall contribution to the national economy is non-negligeable when compared to that of important industrial activities such as meats and processed goods (4.8%); agricultural field crops (3.6%); bananas, coffee and cocoa production (2.6%); and the manufacture of petroleum refinery products (2.0%).

While already indicating a vibrant sector, culture’s contribution to GDP is underestimated by this indicator as it only takes into consideration private and formal cultural activities, excluding the contribution of local cultural activities in the informal sector, as well as non-market cultural activities offered by public agencies or non-profit institutions, both of which are important components of cultural production in Ecuador.

1020

2 CULTURAL EMPLOYMENT: 2.2% (2010)

In 2010, 2.2% of the employed population in Ecuador had cultural occupations (134,834 people). 87% of these individuals held occupations in central cultural activities, while 13% held occupations in equipment/supporting activities. The sub-sectors that contributed the most to national employment included leather and textile handicraft workers (27.9%), architects (7.0%), graphic and multimedia designers (5.6%), advertising and marketing professions (5.5%), and printers (4.4%).

This data indicates that thanks to cultural occupations, many Ecuadorians benefit from the generation of income and enhanced wellbeing. Furthermore, cultural occupations enable creativity and the exercise of cultural rights, and thanks to the unique characteristics of the culture sector and its dependence on locally-run micro, small and medium enterprises, cultural employment also facilitates the distribution of wealth to those most in need.

While these results already emphasize culture’s significant role as an employer and generator of wellbeing, the global contribution of the culture sector to employment is underestimated in this indicator due to the difficulty of obtaining and correlating all the relevant data. This figure likely does not cover all informal employment in the culture sector due to the reluctance of some participants to convey such occupations during official surveys, and it does not cover induced occupations with a strong link to culture, or cultural occupations performed in non-cultural establishments. Nevertheless, in regards to the latter constraint, an additional indicator illustrates that 2.3% of the total employed population worked in cultural establishments in 2010, highlighting a similarity to the core indicator and reinforcing its validity.

1021

3 HOUSEHOLD EXPENDITURES ON CULTURE: 3.41% (2003)

In Ecuador, 3.41% of household consumption expenditures were devoted to cultural activities, goods and services in the year 2003 (403,066,224.24 USD). 47% was spent on central cultural goods and services, and 53% on equipment/supporting goods and services. The purchase of books was responsible for the largest share of central goods and services consumed (15.6%), followed by the consumption of cultural services (10.3%). Cultural services include entry fees to cinemas, museums, theatres, concerts, national parks and heritage sites, the hire of equipment for culture (televisions, video cassettes) etc. The purchase of equipment for the reception, recording and reproduction of sound and pictures such as televisions, radios, stereos etc.), and the purchase of equipment for information processing were responsible for the largest shares of equipment/supporting goods and services (31%, 16%).

This result suggests a significant demand for cultural goods, though variations in the consumption of cultural goods and services can be noted across income quintiles suggesting that an increase in consumption of cultural goods corresponds to an increase in wealth. While the lowest income quintile spends 2.12% of household expenditures on culture, households in the highest income quintile spend 4.28% of total expenditures on culture. Furthermore, across income quintiles it can be noted that lower earning households spend proportionally more on equipment/supporting goods, which are often a prerequisite to access certain forms of cultural content, while wealthier households spend proportionally more directly on central cultural goods and services. This data should be taken into account when analyzing policies and mechanisms in place to permit individuals of all income groups to participate in cultural activities and the consumption of cultural goods and services.

Though already significant, the final result of 3.41% is a sub-estimation of the total actual consumption of households. It does not account for the value of cultural goods and services acquired by households and provided by non-profit institutions at prices that are not economically significant (e.g. in-kind transfers). For example, it does not include museum and public library services and free public cultural events that may represent a significant portion of cultural consumption.

>> Globally, these results highlight the dynamism of Ecuador’s culture sector and how Ecuadorian cultural industries and enterprises are making a non-negligeable contribution to the national economy in regards to domestic production, consumption and the creation of jobs. In light of the objectives of Policy 11.1 of the National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013) concerning the development of an endogenous, sustainable and diversified economy, culture’s role merits greater consideration when taking action to effectively implement national policy.

1022

4 INCLUSIVE EDUCATION: 0.97/1 (2010)

A key goal stated in the National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013) is to review government investment in education in order to enable the development of skills that allow citizens to participate in cultural life, society and the economy, as well as to appreciate and enhance cultural diversity. Within this context, the result of 0.97/1 reflects the success of national authorities in guaranteeing the fundamental cultural right to an education in a complete, fair and inclusive manner. This result shows that on average, the target population aged 17-22 has 11.1 years of schooling, which is superior to the targeted 10 years. In addition, only a small minority of 3% of the target population lives in education deprivation, having less than 4 years of schooling. This result shows that public authorities’ efforts have been overwhelmingly successful in assuring that citizens enjoy the right to an education, and participate in the construction and transmission of values, attitudes and cultural skills throughout school, as well as benefit from the personal and social empowerment of learning. Nevertheless, to further enhance equality and education, targeted policies may still be necessary to address lower average years of schooling amongst African and indigenous populations (4.2 and 6.9 years respectively), which have been indicated as key issues in the Plurinational Plan to Eliminate Racial Discrimination, Ethnic and Cultural Exclusion (2009-2012).

1023

5 MULTILINGUAL EDUCATION: 62.5% (2009)

The 2008 Constitution of Ecuador states that “the national education system will integrate an intercultural vision and the State shall ensure a system of bilingual intercultural education […] respecting the rights of communities, towns and nations” (Arts. 347). In this system, the main language to be used for teaching is to depend on identification with a cultural group, while Spanish is to be utilized for intercultural relations.

According to the 2009 official curriculum, 37.5% of the hours to be dedicated to languages in the first two years of secondary school is to be dedicated to the teaching of the official national language - Spanish. The remaining 62.5% of the time is to be dedicated to the teaching of international languages. These results indicate that while the official curriculum is designed to promote linguistic diversity on the global scale, additional efforts are necessary to meet national objectives of promoting the diversity of local Ecuadorian languages and culture. 0% of the required national curriculum is to be dedicated to teaching any of the 14 State-recognized local languages associated with indigenous nations.

Nevertheless, a recent reform by the Ministry of Education calls for the teaching of languages in schools to facilitate and enhance cultural diversity, recognizing language’s role in the construction of an intercultural and plurinational country. The implementation of these reforms may effectively change the results for this indicator in the near future, establishing more balance between the promotion of international and Ecuadorian linguistic diversity. The results for this indicator merit consideration when analyzing the indicators of the Heritage and Social Participation dimensions, as the promotion of multiple Ecuadorian identities through education may also contribute to the protection of intangible cultural heritage, as well as facilitate greater social cohesion amongst the peoples of Ecuador.

1024

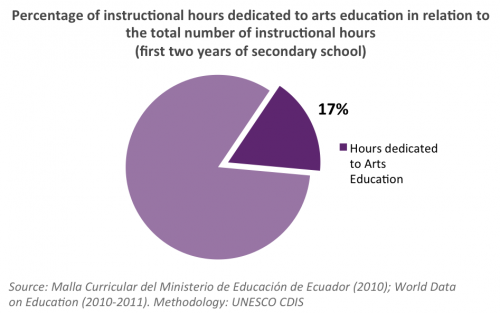

6 ARTS EDUCATION: 17% (2009)

In Ecuador, a national average of 17% of all instructional hours in the first two years of secondary school are to be dedicated to arts education, reflecting a high level of priority given to the arts and culture that is consistent with recent Ministry of Education reforms that recognize the teaching of the arts as fundamental to enhance cultural diversity. Ecuador’s result is significantly greater than the average score for all CDIS countries, which is situated at 4.84%.

Courses included under the category of arts education in Ecuador are meant not only to stimulate artistic talent, but to ensure the development of both informed producers and consumers of cultural and artistic expressions, widening horizons for personal development and cultural participation through the creation of an educated audience. Examples of subjects taught include art history, artistic creation activities, and aesthetics applied to cinema, theatre, dance, comics, and music. Teaching in these fields also undoubtedly contributes to develop students’ interest in further academic training and a professional career in the culture sector. Learning on such topics may also become significant stimuli for creativity and strengthen employment potential in fields such as innovation, design, and the production of goods and services.

1025

7 PROFESSIONAL TRAINING IN THE CULTURE SECTOR: 0.7/1 (2013)

Ecuador’s result of 0.70/1 indicates that although complete coverage of cultural fields in technical and tertiary education does not exist in the country, the national authorities have manifested an interest and willingness to invest in the training of cultural professionals.

While various technical and tertiary courses are offered in the areas of music, visual arts, and heritage, notable gaps exist regarding technical training opportunities in film and image and the complete lack of cultural management courses at either the technical or tertiary level. Transforming artistic and creative capacities into economically viable activities, goods and services and the effective management of cultural businesses requires considering culture-specific aspects of the sector. A lack of training in cultural management may hinder the emergence of a dynamic cultural class and the development of competitive cultural enterprises. The University of the Arts that is currently being constructed is hoped to address such shortcomings in the training of cultural professionals.

1028

8 STANDARD-SETTING FRAMEWORK FOR CULTURE: 0.96/1 (2013)

Ecuador’s result of 0.96/1 indicates that there is already a significant standard-setting framework for culture when looking at the country as a whole and that many efforts have been made to ratify key international legal instruments affecting cultural development, cultural rights and cultural diversity, as well as to establish a national framework to recognize and implement these obligations.

Ecuador scored 0.95/1 at the international level, demonstrating a high level of commitment to cultural rights, cultural diversity and cultural development. Ecuador has ratified nearly all recommended international conventions, declarations and recommendations such as the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the WIPO Copyright Treaty. However, Ecuador has yet to ratify select international instruments such as the Universal Copyright Convention and the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

At the national level, a score of 0.96/1 indicates that a great deal of effort has been made to implement many of the international obligations that Ecuador has committed to at the country level. On-going national reforms have resulted in the explicit integration of internationally agreed principles regarding heritage protection, the promotion of cultural diversity and the rights of indigenous people into national law. The National Charter of Rights and Justice (2008) establishes the framework for universal, cultural and collective rights. Using the Charter as a basis, on-going reform has led to building the National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013), which outlines 12 goals and policies for the construction of an intercultural and plurinational state. The framework law on culture, as well as other specific laws concerning cultural fields, continue to be under review by the National Assembly. Reform is meant to better adapt laws to the new model for Good Living and the recommendations of international bodies, individuals and cultural groups regarding the possible enhancement of the standard-setting framework for culture. Particular care is being taken regarding reform of copyright and intellectual property law to assure that the State guarantees universal access to knowledge, information and culture without harming rights of creators. One omission to be noted in Ecuador’s national-level standard-setting framework is the absence of laws, regulations or decrees promoting cultural patronage and facilitating the private sector’s support of culture. It is hoped that on-going reform will address this absence.

1029

9 POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR CULTURE: 0.95/1 (2013)

The final result of 0.95/1 reflects that national authorities have taken great efforts to create a comprehensive policy and institutional framework to promote the culture sector as part of development, by establishing targeted policies and mechanisms and by having an adequate political and administrative system to implement the legal instruments seen above. Ecuador’s results are above the average result of test phase countries of the CDIS, which is situated at 0.79/1, further emphasizing the exceptional commitment of authorities.

Ecuador scored 1/1 for the Policy Framework sub-indicator indicating that a comprehensive body of well-defined culture and sectoral policies and strategies has been put in place to promote culture in the country. Ecuador scored 0.92/1 for the Institutional Framework sub-indicator, which assesses the operationalization of institutional mechanisms and the degree of cultural decentralization. Many positive factors and recent developments account for such a result. In 2007, the Coordinating Ministry of Heritage and the Ministry of Culture were founded, creating ministry level bodies responsible for cultural activities. In addition, decentralized representations of the latter have been established in all 24 provinces to assure adequate cultural governance and effective policy implementation at all levels. Decentralization extends to the municipal level as well, and some obstacles continue to be encountered in the applying of new mandates. New binding constitutional mandates call for Autonomous Decentralized Governments (GAD) to take charge of cultural management. This remains a challenge and is a major change from previous optional State decentralization models; municipalities must now include the implementation of cultural projects and programs in their planning resources, as well as coordinate with the various levels of government. In addition to increased decentralization, a new organizational process called the National Culture System was established in 2008 to clearly structure policy making and implementation of culture projects. The Ministry of Culture is at the top of the hierarchy of this new system, and is to be directly followed by five sub-secretaries. The new system calls for coordination with other ministries such as the Coordinating Ministry of Heritage, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion, as well as increased links with private entities and artists, cultural managers, cultural networks and others key stakeholders. The system continues to be gradually implemented and internalized by all institutions concerned, but some outstanding issues still remain regarding the configuration of the system and the effective creation of sub-secretaries, as well as the abilities of administrators to effectively manage. The latter may in part be resolved by increasing training opportunities in cultural management as highlighted by the Education dimension. Finally, apart from these many achievements, a key gap that remains in Ecuador’s institutional framework is a lack of mechanisms and processes to monitor, evaluate and review cultural policies within this new system, which is crucial to assure the achievement of goals and national targets proposed in the National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013).

1030

10 DISTRIBUTION OF CULTURAL INFRASTRUCTURES: 0.57/1 (2012)

One of the goals of the National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013) is to "build and strengthen public, intercultural and common venues,” assigning the State the responsibility to "ensure free public circulation and create mechanisms to revitalize memories, identities and traditions, as well as expose existing cultural creations." The Plan recognizes public cultural venues as essential for the development of cultural activities and social participation, which directly contribute to economic and social development.

On a scale from 0 to 1, Ecuador’s result for this indicator is 0.57, 1 representing the situation in which selected cultural infrastructures are equally distributed amongst Provinces according to the relative size of their population. The score of 0.57 thus reflects that across the 24 provinces of Ecuador, unequal distribution of cultural facilities remains.

When looking at the figures for the three different categories of infrastructures, Ecuador scores 0.59/1 for Museums, 0.38/1 for Exhibition Venues Dedicated to the Performing Arts and 0.73/1 for Libraries and Media Resource Centers. This suggests that the most equal distribution of access exists for Libraries, and that the most unequal distribution for Exhibition Venues. All provinces have a minimum of 30 Libraries and the provinces with the highest numbers are indeed those with the largest populations. For example, the Guayas province has 24% of all Libraries (1,983) and is home to 25% of the national population. Higher figures regarding Libraries is undoubtedly explained by long-standing Education policies that favour the creation of such venues as part of a strategy to eliminate of illiteracy, improve formal education, and promote reading. Such objectives have a history as national priorities compared to the newer emphasis placed on the importance of cultural infrastructures in the National Plan for Good Living. For Museums and Exhibition Venues, greater imbalances in the distribution of facilities can be noted. The Los Rios, Orellana, Pastaza, and Santa Elena provinces have no Exhibition Venues, and in addition to having no Exhibition Venues, the Sucumbíos and Galápagos provinces have only 1 Museum but the size of their populations are rather modest. Overall, most facilities are concentrated in urban areas. While representing 18% of the population, the capital province of Pichincha has 29% of all Museums, 31% of Exhibition Venues and 21% of Libraries. The distribution of cultural infrastructures is a crucial and common challenge among all countries that have implemented the CDIS, as the average score for this indicator is 0.43/1.

1031

11 CIVIL SOCIETY PARTICIPATION IN CULTURAL GOVERNANCE: 0.90/1 (2013)

The final result of 0.90/1 indicates that many opportunities exist for dialogue and representation of both cultural professionals and minorities in regards to the formulation and implementation of cultural policies, measures and programmes that concern them. Such opportunities for participation in cultural governance exist at the national as well as regional and local levels. While Ecuador received a score of 0.95/1 for the participation of cultural professionals, a slightly lower score of 0.85/1 was established for the participation of minorities due to the non-permanent nature of participation opportunities for the latter.

Since the Constitutional reform of 2008, participation has become a cornerstone of institutional processes and recognized as the fourth function of the State. To ensure the exercise of participation and that individuals and communities are able to influence decision-making on laws, policies, and measures that concern them, the government has delineated a series of mechanisms and bodies. The mechanisms for participation are diverse and vary according to the government institution and theme concerned; they include open forums, assemblies, public deliberation, roundtables, civic networks, oversight committees, and popular councils. One such mechanism is the Council of Citizen Participation and Control, which is to exercise social control of public sector bodies, as well as private sector bodies that perform activities of public interest. More specific to government bodies responsible for culture, the Coordinating Ministry of Heritage and the Ministry of Culture have established Consultative Committees as a means for participation. The Committees meet in ordinary and extraordinary circumstances and among other functions, they release opinions on the Ministries’ policies, programs and projects. Their opinions are taken into account on a consultative basis. The Committees aim for balance amongst members regarding their sex, age, ethnic and cultural representation. In addition, Committee members are desired to have knowledge of the subject at hand, making it possible for cultural professionals to be heard.

1033

PARTICIPATION IN GOING-OUT CULTURAL ACTIVITIES: 8.4% (2012)

In 2012, 8.4% of the people polled in Ecuador reported having participated at least once in a going-out cultural activity in the last 12 months. Going-out cultural activities include visits to cultural venues, such as cinemas, theatres, concerts, music festivals, galleries, museums, libraries, historical and archaeological monuments and museums abroad. Such activities require people actively choosing to attend a particular cultural activity, thus providing insight into the degree of cultural vitality and appreciation of culture. They also imply physical places for encounters to occur between audiences and artists, as well as among audiences, and thus insight into the degree of social interaction and connectivity. A result of 8.4% suggests a low degree of cultural participation and that only a small minority of the population visit cultural venues and institutions.

Of the 8.4% of the population that responded yes to having participated in going-out cultural activities, nearly half (48.3%) were between the ages of 12 and 25, while only 7.7% of respondents were 61 or older. 63.3% of those having participated in such activities were from urban areas while only 36.7% were from rural areas. Cross-analysis with the Governance dimension reveals that such figures may in part be explained by the concentration of cultural infrastructures in urban areas like the capital province of Pichincha while other more rural Provinces lack adequate facilities. Thus, increasing equitable access to infrastructures may have a positive impact on cultural participation and thus the consumption of cultural goods and services as well as social connectivity.

1035

14 TOLERANCE OF OTHER CULTURES (ALTERNATIVE INDICATOR): 67.7% (2011)

In 2011, 67.7% of the people of Ecuador agreed that they do not find people of a different skin colour as undesirable neighbours. This indicator provides an assessment of the degree of tolerance and openness to diversity, thus providing insight into the levels of interconnectedness within a given society.

A result of 67.7% indicates that the values, attitudes and convictions of approximately two-thirds of Ecuadorians favor the acceptance of other racial and cultural groups. Little variation in the results appears across sexes. Some variation across age groups can be noted though not representing a clear increase or decrease with age. While 67.7% of respondents aged 15-40 expressed tolerance for other racial and cultural groups, a slightly lower 67% of people aged 41-60 responded favourably, while a higher 69.9% of respondents over 61 years old answered positively.

As the majority of the population expressed opinions of openness, these results could be interpreted as reflecting a cultural context and system of values that regards difference and diversity as capital for progress, enabling an environment conducive to development and well-being through the promotion of tolerance, reciprocity and mutual respect. Widespread valorization and progress regarding the appreciation for cultural diversity is also reflected in the advances made in the Constitution regarding the recognition of the many cultures of Ecuador (Art. 275).

1036

INTERPERSONAL TRUST: 16.6% (2010)

In 2010, 16.6% of the people of Ecuador agreed that most people could be trusted. This indicator assesses the level of trust and sense of solidarity and cooperation in Ecuador, providing insight into its social capital. A result of 16.6% indicates a low level of trust and solidarity. Variations in the results can be seen across age groups. While 18.4% of people aged 16-25 and 18.2% of people aged 61 and above agree that most people can be trusted, only 15.7% and 15.2% of those aged 26-40 and 41-60 agree, respectively. Nurturing interpersonal trust is a common obstacle for countries having implemented the CDIS, as the average for all countries is situated at 19.2%.

Cross-analysis with the other indicators of this dimension suggests that there remains an obstruction to transforming widespread feelings of tolerance and openness into sentiments of trust and solidarity. Through improved access and rates of engagement, enhancing the potential of cultural participation to reinforce feelings of mutual understanding, solidarity and cooperation, merits consideration.

1037

FREEDOM OF SELF-DETERMINATION: 6.78/10 (2008)

Ecuador’s final result is 6.78/10, 10 representing the situation in which individuals believe that there is ‘a great deal of freedom of choice and control’ and 1 being ‘no freedom of choice and control.’ The score of 6.78/10 indicates that the majority of the population feels that they have control over their lives and are free to live the life they choose, according to their own values and beliefs. Self-determination is recognized as an individual’s human right in international covenants. By assessing this freedom, this indicator evaluates the sense of empowerment and enablement of individuals for deciding and orienting their economic, social and cultural development.

This result suggests a level of individual agency in Ecuador in line with the average results for all countries having implemented the CDIS, which is also situated at 6.7/10. This indicates that for the majority of citizens, Ecuador provides the necessary enabling political, economic, social and cultural context for individual well-being and life satisfaction and builds common values, norms and beliefs which succeed in empowering them to live the life they wish.

1026

17 GENDER EQUALITY OBJECTIVE OUTPUTS: 0.89 /1 (2013)

In Ecuador, gender equality is deemed an integral part of the exercise of universal rights, and fundamental for the practice of democracy. The guarantee of gender equality suggests that no one is subjected to the will of others and that all citizens have equal opportunities to be active members of society as well as political, social and cultural life. Within this context, the result of 0.89/1, reflects the significant efforts made by the Ecuadorian government in order to elaborate and implement laws, policies and measures intended to support the ability of women and men to enjoy equal opportunities and rights. Ecuador’s result is substantially higher than the average result for test phase countries of the CDIS, which is situated at 0.64/1.

While Ecuador has a positive result overall, a detailed analysis of the four areas covered by the indicator reveals persisting gaps where additional investment or enforcement is needed to further improve basic gender equality outputs. A comparison of the average number of years of education for men and women aged 25 years and above reveals little divergence. On average, both men and women have over 7 years of education and thus similar opportunities to gain skills and knowledge that permit further personal development. Targeted gender-equity legislation focused on violence against women has also been adopted. However, while a quota system to facilitate the political participation of women is likewise currently in place, a significant imbalance in political participation persists. In 2012, women represented only 32% of parliamentarians. The recent 2012 reform of the Regulations for Internal Democracy requires the sequential alternation of male and female candidates for primary elections within political parties and movements, and in the case that such a rotation does not occur, the National Election Council may reject the internal election process (Article 3 and 11). Enforcement of these new regulations is hoped to increase the number of women parliamentarians in the future. Additionally, progress still can be made regarding labour force participation; where 78% of men are either employed or actively searching for work, versus 47% of women. Furthermore, according to the Plurinational Plan to Eliminate Racial Discrimination, Ethnic and Cultural Exclusion (2009-2012), women’s average rate of urban unemployment exceeds the national average by 2.71% and women continue to earn 20-50% less than men with similar occupations.

In conclusion, while Ecuador has made many achievements in the area of gender equality, progress remains to be achieved in select areas. Some women, and indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian women in particular, continue to face discrimination in the different spheres of social, political, economic and cultural life. Though policies and mechanisms are in place, policies require people, and a further look at the alternative subjective indicator below reveals the persistence of negative cultural values, attitudes and practices amongst many Ecuadorians, which may impede the effective realization of complete gender equality.

1027

18 PERCEPTION OF GENDER EQUALITY (ALTERNATIVE INDICATOR): 59.85% (2009)

In 2009, 59.85% of Ecuadorians positively perceived gender as a factor for development, according to their responses to questions regarding employment and political participation. The final result is a composite indicator, which suggests that just over one-third of the population of Ecuador continue to view gender as irrelevant or a negative factor for development. Individuals’ perceptions on gender equality are strongly influenced by cultural practices and norms, and Ecuador’s result suggests that some gender-biased social and cultural norms remain.

However, the perception of gender equality fluctuated according to sex and age. While 57.75% of Ecuadorian men positively perceived women’s role in employment and politics, a slightly higher 61.45% of women felt the same way. Likewise, while the lowest figures were recorded for the oldest group of the population aged 61 and above, 55.85%, the most positive perceptions were recorded amongst the youngest respondents aged 15 to 20 years, 63.05%.

Moreover, the perception of gender equality regarding employment and political participation varied. When asked if “It is best for women to be at the house and for men to be at work,” 55.8% of all respondents did not agree. This means that 44.2% of the population agrees that men have priority in regards to employment. This figure correlates with the gaps in objective outputs observed in this domain. However, when asked if “Men make better political leaders than women,” 63.4% of the population responded no. While this indicates that one-third of the population still poorly perceives women’s role in political participation, it also suggests that the majority of the population positively perceive women in politics. This opinion is not mirrored in the significant ongoing gap in the objective outputs of women’s political participation in Ecuador.

>> This cross-analysis of the subjective and objective indicators reveals inconsistencies between forward-looking national legislation for gender equality and the population’s attitudes and values in select areas. These results suggest a need for greater advocacy efforts targeting attitudes concerning such topics as labour participation, as well as enhanced measures and public investment to assure the translation of values into performance outcomes and effective opportunities for men and women in politics. Since cultural values and attitudes strongly shape perceptions towards gender equality, it is critical to demonstrate that gender equality can complement and be compatible with cultural values and attitudes, and be an influential factor in the retransmission of cultural values for building inclusive and egalitarian societies, and for the respect of human rights.

1017

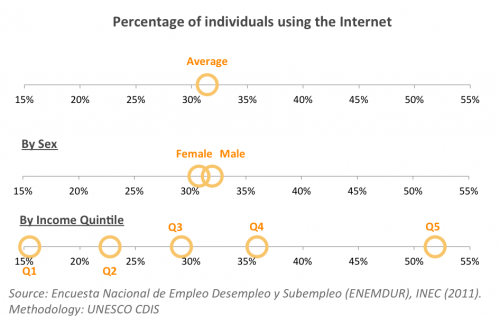

20 ACCESS AND INTERNET USE: 31.4% (2011)

In 2011, 31.4% of the national population over the age of 5 used the Internet in Ecuador. Ecuadorians access the Internet via various mediums such as public and personal computers, mobile phones and other electronic devices. Significant variations in the results can be seen across income quintiles, ranging from 15.5% of the poorest group of the population to 51.9% of the wealthiest portion of Ecuadorians.

The development of information technologies, and in particular the Internet, is significantly transforming the way people access, create, produce and disseminate cultural content and ideas, influencing people’s opportunities to access and participate in cultural life. Such figures demonstrate ongoing barriers to equal opportunities for all Ecuadorians to enjoy such forms of communication and means for cultural dialogue and participation. The National Plan for Good Living (2009-2013) sets goals to address this issue, aiming for 55% of rural education facilities and 100% of urban education facilities to have access to the Internet, as well as to provide 50% of all households with a landline for Internet access by 2013.

1018

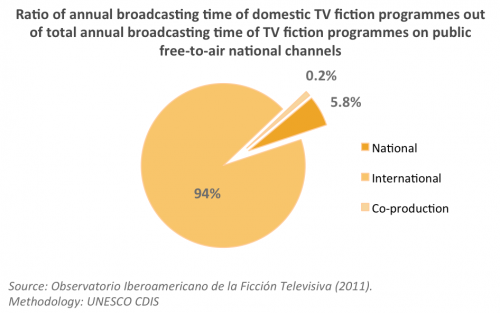

21 DIVERSITY OF FICTIONAL CONTENT ON PUBLIC TELEVISION: 6% (2011)

In 2011, 6% of the broadcasting time for television fiction programmes on public free-to-air television in Ecuador was dedicated to domestic fiction programmes. 96.7% of this time was dedicated to uniquely Ecuadorian productions while the other 3.3% of the time was spent airing co-productions between Ecuadorian and foreign producers.

In contrast, the 2013 Communication Law aims for 60% of programmes on national television to be of Ecuadorian origin and that 10% should be independent national productions (Art. 97). Within this context, the ratio of 6% indicates a low percentage of domestic fiction productions within public broadcasting, well below the average result for all countries having implemented the CDIS, which is situated at 25.8%. 94% of all broadcasting time is dedicated to foreign fiction programmes, indirectly reflecting inadequate levels of public support of the dissemination of domestic content produced by local creators and cultural industries.

While government support of national film production has resulted in a 300% production increase of nationally produced films between 2007 and 2012 according to the National Film Board, thanks to new mechanisms like the Promotion of National Cinema Act (2006) and the National Film Fund, additional support of local fiction productions for public broadcasting could further stimulate the audio-visual sector and the flourishing of local cultural expressions and creative products. One possible way to build-up the audio-visual sector would be to intensify co-productions with regional neighbours in order to boost domestic production through creative cooperation and expanding the market for domestic fictional content. In addition, cross-analysis with the indicators of the Governance, Education and Economy dimensions reveals that though sectoral laws and policies for film and television are in place, there are only limited opportunities to conduct studies in the field of film and image, as well as limited employment. Refining existing policies and assuring their effective implementation could further facilitate the sector by increasing education opportunities and decreasing barriers for employment.

In addition to boosting the production of Ecuadorian cultural industries, enhancing support of the dissemination of local fiction programmes could not only expand audience’s choices, but it may increase the population’s level of information on culturally relevant issues while helping to strengthen identities and promote cultural diversity.

1032

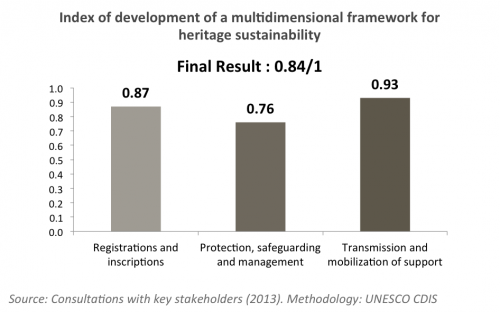

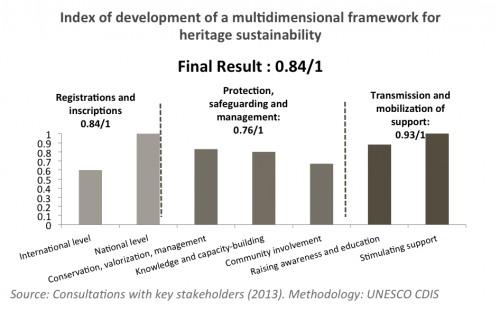

22 HERITAGE SUSTAINABILITY: 0.84/1 (2014)

Ecuador’s result of 0.84/1 is reflective of the high level of priority given to the protection, safeguarding and promotion of heritage sustainability by Ecuadorian authorities. While many public efforts are dedicated to registrations and inscriptions, conservation and management, capacity-building, community involvement and raising-awareness, select persisting gaps call for additional actions to improve this multidimensional framework.

Ecuador scored 0.87/1 for registration and inscriptions, indicating that authorities’ efforts have resulted in many up-to-date national and international registrations and inscriptions of Ecuadorian sites and elements of tangible and intangible heritage. Ecuador has 93,075 cultural heritage sites on their national registry, as well as a national inventory of 6,936 elements of intangible heritage. Government efforts have successfully resulted in 4 heritage sites receiving recognition of being World Heritage – the City of Quito (1978), the Galapagos Islands (2001), Sangay National Park (2003) and the Historic Centre of Santa Ana de los Ríos de Cuenca (1999); as well as 2 elements of intangible heritage being included on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity ¬– Oral heritage and cultural manifestations of the Zápara people (2008) and Traditional weaving of the Ecuadorian toquilla straw hat (2012).

Ecuador scored 0.76/1 for the protection, safeguarding and management of heritage, indicating that there are several well-defined policies and measures, but certain key gaps persist. Though cross-analysis with the Education dimension draws attention to a lack of regular technical and vocational training opportunities in the area of heritage, the results of this indicator highlight the comprehensive coverage of multiple programmes carried out to increase heritage site management staff’s expertise, communities’ knowledge of intangible heritage, and to increase expertise concerning illicit trafficking. However, gaps in the framework can still be identified. No specific capacity building and training programmes for the armed forces regarding the protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict have been implemented in the last 3 years. Other gaps include the lack of updated or recent policies and measures for safeguarding inventoried intangible heritage and the lack of Disaster Risk Management plans for major heritage sites. Finally, while authorities recognize that local communities are to be included in registry and inventorying processes for intangible heritage, no recent measures or practices have been adopted to respect customary practices governing access to specific aspects of intangible cultural or to include communities in the registry and identification processes for tangible heritage.

Ecuador scored 0.93/1 for the transmission and mobilization of support, which reflects the tremendous efforts taken to raise awareness of heritage’s value and its threats, as well as efforts to involve the civil society and the private sector in the safeguarding of heritage. In addition to signage at heritage sites and differential pricing, awareness-raising measures include the Coordinating Ministry of Heritage’s publication and distribution of Patrimonio magazine, and the Ministry of Environment’s Guardian of the Planet programme to promote the sustainability of natural heritage amongst school age children. The support of the private sector and civil society is fostered through the issuing of tourism licenses concerning protected areas and civil society organizations’ involvement in the management of major heritage sites such as Sangay National Park and the Galapagos Islands. The framework for heritage sustainability could be further enhanced by the creation of community-managed centres or associations intended to support the transmission of intangible cultural heritage by informing the general public about its importance to the communities themselves.