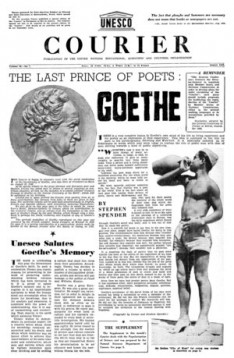

(Copyright by UNESCO and Benedetto Croce)

It has been shrewdly observed that great poets, far from being the interpreters and representatives that great poets, of their far fromown peoples, are their critics, correctors and integrators. Remember Dante and the Florentines, as he saw them; Cervantes and his Spanish contemporaries, crazy about knight-errantry; Shakespeare and the English proverbially correct and cold, which his dramas certainly are not; and Gœthe, serene, well-balanced and thoroughly human, in contrast to his Germans a warlike and fanatical race, serious and hard-working admittedly, but with a considerable share of pedantry.

By Benedetto Croce

Gœthe was not to the taste of the politically-minded among his people, who more than once showed that to his supreme genius they preferred a poet of the second rank, such as Schiller. And when the German national tradition was intensified to the point of delirium, and the first centenary of Goethe's death arrived, in 1932; the demonstrations were prepared with a lack of enthusiasm which clearly repealed the gulf, the ostrangement that separated him from what had then become Hitter's Germany.

Now that misfortune has smitten his great nation-great in its many virtues, its talents and its energy ‒ and at the same time has smitten Europe, thus deprived of a ferce essential to its balance and situated in its geographical centre, what better can Germany do, at this bicentenary of the birth of her mighty poet, than to raise herself towards him in spirit, accept his message and reflect on it anew, with such devotion and sincerity that it shall restore tight to the minds and human feeling to the hearts of his countrymen?

I did not accept the invitation to participate in the honours shown to Goethe in Germany in 1932, for they seemed to me to be insincere. But I turned again to his books and re-read them, and continued to write critical studies about them, as I had done during the first World War, when Germany was lighting against Italy, as I did again during the second war when Italy, having become Fascist, was allied to a Germany that had become Nazi; and as I continued to do at the end of the war, amid the political tasks that I had accepted. And always there came to me from Goethe comfort and serenity and courage, because he always carried me beyond and above the things of the day which is the only way of achieving real union with them, of loving and serving them.

But it was no longer possible for me to speak openly and drectly with the Germans. I mean with those Germans who, like myself, were concerned with philosophy and history and poetry ‒ as I had been used to do in the pre-1914 days, exchanging ideas and suggestions and forming precious and unforgettable friendships with them. And when, in 1936, a Swiss paper asked me to express my opinion about the Germany of that day-which had recently caused a great scandal by having, among other things, altered the names of its cultural publications (for instance, transforming the Review of Cultural Philosophy into the Review of German Cultural Philosophy), and had removed from the pediment of Heidelberg University the inscription, To the Living Spirit, replacing it by: To the German Spint ‒ I sent that Swiss paper an article inspired by the feeling of Goethe, who always detested the idea and the expresssion Deutschtum, and to which I gave the title of "The Germany we used to love". This article could not be published in Germany, or even discussed by my friends there.

The period in which Germany should take most pride is that in which she possessed such a poet as Wolfgang Goethe, who belongs to the small company that is headed by Homer, together with thinkers who to this very day are still masterly and up-to-date-Kant and Hegel and a few others, such as Jacobi, that very noble genius, who deserve to share their high place, and historians and philologists who put fresh life into the study of language and history; not to mention scientists, physicists and mathematicians. Certainly you will say the Germans take great pride in that period when their country was centred on Weimar, even if they are unable to cease loving the other extreme of Potsdam, to which their souls are secretly attracted. Yes, they do take pride in it. But even when they do so with complete sincerity, they do not-if I may be permitted to say so-properly understand its origin and purpose. They regard it as belonging entirely to Germany, or as a specifically German reaction to and rebellion against the culture of Europe as a whole.

What was peculiar to Germany in the age of Weimar was a galaxy of outstanding mmds, such as can only be entirely equalled, perhaps, in the Greece of Pericles'day. Germany was thus able to exert in the world of ideas a hegemony which was conferred upon her, not by her Deutschtum. her Germanism, but by her Europeatum, or rather by that world-spirit which, at other periods of modern history, had conferred the same hegemony upon Renaissance Italy or upon the France of Descartes and Louis XIV, and without which it would have been valueless or inexistent.

The Germany of those days was the legitimate daughter of Europe, taking over the management of the ancient house-not a daughter shut out like a foundlling, and filled with rancour, desire for revenge, and the spirit of destruction and self-assertion. And now this well-deserved and much-desired hegemony returns to her, in conformity with the new feelings and necds of the human race, for the good of us all; and all of us will greet her with emotion and admiration; and our gratitude will perhaps be so great as to make us forget how much of our own strength we have had to give out, in order to revive her and support her so that she should completely fulfil her mission and not, in her turn, yield up the hegemony to another nation which has meanwhile been preparing for the call, as is required by the vicissitudes of things human.