Programme Key Information

| Programme Title | Hametin Família (Strengthening Families) |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organizations | Timor-Leste’s Ministry of Social Solidarity (MSS), in collaboration with other ministries (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, Secretary of State for Youth and Sports, Secretary of State for Social Communication) |

| Language of Instruction | Tetum and local languages |

| Funding | H&M Conscious Foundation |

| Programme Partners | UNICEF, Ba Futuru, Rain Barrel Communications, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Justice, Secretariat of State for Youth and Sports, Secretariat of State for Communications |

| Annual Programme Costs | Approximately USD 162,000 for two municipalities per year |

| Date of Inception | 2014 |

Country Context and Background

Timor-Leste has made remarkable progress in education since independence was restored in 2002. The adult literacy rate (those aged 15 years and older) has increased from 37.5 per cent in 2001 to 64.07 per cent in 2015 (UIS, 2015); the number of out-of-school children has dropped from 42,887 in 2008 to 5,310 in 2015 (UIS, 2015). However, despite these successes, Timor-Leste still faces numerous challenges in early childhood care and basic education in non-urban areas, including poor school infrastructure and facilities, low quality of teaching, and limited learning materials (UNESCO, 2015); these challenges are exacerbated by the fact that 68 per cent of the population live in rural areas, while 42 per cent are under the age of 14.

According to the Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey (NSD, 2010), the country still has much to do to improve the care of infants and children, and child mortality rates are still high: for the under-fives the figures stand at 87 deaths per 1,000 live births in rural areas and 61 deaths per 1,000 live births in urban areas. These high numbers are due to poor access to health care, weak infrastructure and communication systems (road, transport, and telecommunication), and unhealthy indigenous practices in rural areas. In addition, 50.2 per cent of under-fives have stunted growth and 38 per cent are underweight (UNICEF, 2013).

Even where health-care facilities are available, women reported several concerns, the most common of which were lack of medicines and health-care providers, and long distances to the facilities (ibid). The report also identified a need to strengthen parents’ knowledge of good practices in early childhood care and development, as well their understanding of the importance of attending pre-school (ibid).

The Timorese government has implemented a series of initiatives to address these challenges with the support of international organizations and NGOs, not only through the improvement of infrastructure and facilities but also through better teacher training and improved parenting skills.

Programme Overview

Hametin Família aims to empower parents and caregivers and generate positive changes in their behaviour, to improve developmental outcomes for children and youth from disadvantaged communities in Timor-Leste. This government programme has been co-developed by the Ministry of Social Solidarity (MSS), the NGO Ba Futuru, development and social justice consultancy Rain Barrel Communications, and UNICEF Timor-Leste, together with input from and consultation with groups of individual stakeholders within government, development partners, and INGOs and NGOs with local bases. Other stakeholders at the community level include village council members such as xefe suku (community chiefs), xefe aldeia (small-village chiefs), women’s representatives, and key agents such as teachers and traditional leaders.

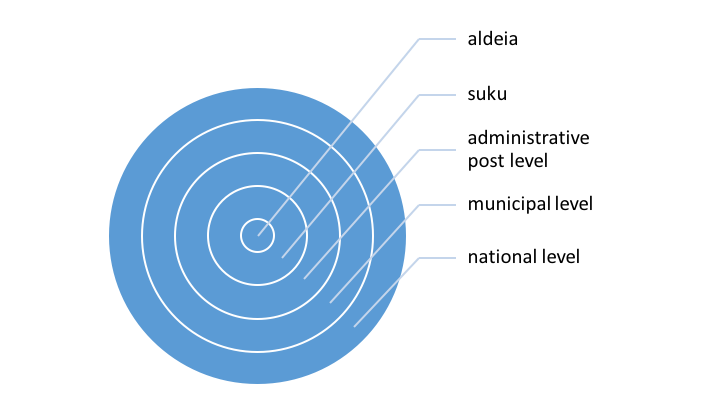

The development of the programme was based on analysis of local culture, government goals, the findings from a review of international best practices, and a knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) baseline study of Timor-Leste. Its three-tier structure mirrors Timor-Leste’s administrative hierarchy, the smallest of which, the suku (community), can comprise one or several aldeias (small villages). This approach is described in more detail later.

The programme launched its first phase in 2014 and concluded its second phase in April 2016. It is currently in its third phase, which will last until November 2017.

Aims and Objectives

The overall goal of this programme is to empower parents and caregivers and promote positive practices among them to improve developmental outcomes for disadvantaged children in Timor-Leste. Specific objectives include:

- To improve the knowledge, attitudes and practices of parents and other primary caregivers in regard to general positive parenting, early stimulation, child protection, alternative discipline, education, nutrition, hygiene and sanitation, health, birth registration and adolescent issues.

- To foster the development of children, adolescents and young people up to the age of 18 through their parents’ and caregivers’ participation in the programme.

Programme Implementation

Hametin Família was developed in three phases:

- Phase I lasted from February to May 2014. It included a study – conducted by Dr. Ritesh Sha from the University of Auckland, a consultant contracted by UNICEF and MSS – mapping existing parenting programmes, the needs assessment of caregivers, and a partnership/stakeholder analysis. The results of this phase were included in the framework for the parenting programme.

- Phase II took place from June 2015 to April 2016. In this phase, the development of the parenting programme was finalized (Parenting Education Curriculum, Youth Theatre Guides and Media Campaign, and Home Visiting Framework), and the programme was piloted in selected administrative posts (between municipal and suku level). Findings from a baseline survey on the KAP of caregivers, who were among the recipients of a stipend from the Bolsa da Mãe programme (a conditional cash transfer programme for parents, initiated by Timor-Leste’s government), informed the design and activities of this phase. A monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework was also created to ensure changes in parenting practices could be monitored, measured and attributed to the programme intervention.

- The implementation of the programme forms the third phase, which started in May 2016 and will conclude in November 2017.

The KAP survey revealed that 80 per cent of parents were not aware of the importance of early stimulation. Around 80 per cent could not recognise the common signs of illness in children. It also reported a high level of parental neglect of children under the age of five, and instances of emotional and physical violence towards children.

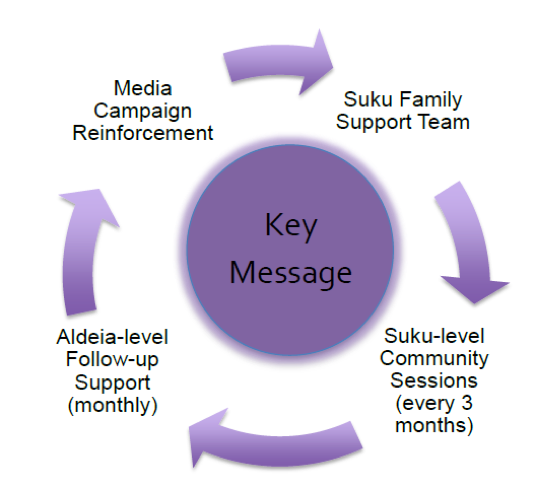

To strengthen parenting knowledge, the programme uses a holistic, integrated, three-tiered approach for the reinforcement of key messages:

- At the national level, a communication campaign comprising 48 episodes of radio drama and broadcast announcements has been established. The episodes, developed by the NGO Leste Art in partnership with the Secretary of State for Social Communication (SECOMS), are aired twice a week. They are accompanied by the distribution of campaign messages, which make use of information, education and communication (IEC) materials, such as flip charts, booklets, posters and banners, with key messages for parents. This communication strategy is enhanced by a Youth Theatre company that performs plays containing key messages to reinforce positive parenting. The company performs in public places at the community level every three months.

- At the community (suku) level, activities include 10 parenting skills meetings per year (around one per month), delivered by facilitators nominated by local communities. These nominations come after selection based on the following criteria: facilitators should be willing to engage in activities for the benefit of their community; have completed high school, or education to an equivalent level; and have experience with community activism. The sessions are backed up by a Family Support Team, consisting of five to 10 local leaders and key influencers who have successfully engaged with their local community. This team also plays a role in coordinating follow-up support activities as described below.

- At the small-village (aldeia) level, follow-up activities such as home visits and the establishment of peer support groups for vulnerable households (i.e. families with children with disabilities, teen parents and others identified as needing additional support) are carried out by members of the Family Support Team. Peer support groups are formed so that those parents who are able to attend parenting sessions can share what they have learnt with others within their networks. Activities at the aldeia level also help reinforce messages from the community parenting sessions.

Additionally, in between national level and suku level, there are two additional administrative levels that play a role in the coordination, implementation and monitoring of the programme. Specifically:

- At municipal level an employee is responsible for coordinating the implementation of activities at suku level, and monitoring reports sent back to the national level. He or she is also in charge of distributing materials throughout each municipality, and authorizes any amendments made in response to issues that emerge during the implementation process.

- At administrative post level (between municipal and suku level), MSS staff and a trainer-mentor work together, utilizing their strengths to assist the work of the Family Support Team at suku level. While MSS staff have well-established relationships with local leadership, and knowledge and experience of working with vulnerable families, the trainer-mentor brings in facilitation skills and knowledge of local parenting practices.

In addition to the activities described above, Hametin Família began a partnership with the community-based Alternative Preschool programme in January 2016, an initiative launched by the Ministry of Education and implemented by local NGOs with the support of UNICEF. The aim of this partnership is to boost the impact of the Hametin Família programme through improved links between adult education, early childhood development and child protection.

One result is that, while adult participants are taking part in Hametin Família programme activities, their children are enrolled in preschools. Parents also spend time with their children once a month during parenting sessions to practise what they have learned in the programme, and engage in learning activities with their children in the preschool.

Altogether, these activities are designed to improve developmental and educational outcomes for children and their families. The overall approach is driven by Communication for Development (C4D) principles, which focus on fostering positive practices to improve health, education and development outcomes in communities.

Programme Content (curriculum) and Teaching Materials

Based on the findings of Phase I, and in consultation with various stakeholders, Ba Futuru developed two manuals, along with other training materials, to be used in the community sessions. Ten focus areas are covered in ten teaching modules:

- General parenting: highlights a child’s need for unconditional love, verbal and physical affection, emotional security, and sensitivity towards their needs and feelings.

- Early stimulation: teaches interaction with children through different developmental stages; activities include games and play, songs, rhymes, stories and reading.

- Child protection: encourages parents to ensure that children are cared for and supervised by an adult, or by a child older than 10 years (young children in Timor-Leste are often left with siblings who are still young themselves), and teaches how to protect children from physical violence and all forms of abuse.

- Positive discipline: focuses on a shift from traditional punishment – including physical discipline, which can lead to emotional and physical trauma, toxic stress and developmental delays – to positive discipline.

- Nutrition: gives recommendations for parents on how to supplement their young children’s diet and on different kinds of nutritious foods.

- Hygiene and sanitation: emphasizes the importance of hygiene and sanitation for children’s health, and teaches parents how to improve family hygiene practices.

- Birth registration: recommends that parents register their children immediately after birth, and provides help for those whose children are not registered, with a referral to the Ministry of Justice and support throughout the registration process.

- Danger signs and care seeking: helps parents recognize the symptoms of serious illness and how to respond, i.e. by taking their children to health-care facilities; this is difficult because not all communities have such facilities. Part of this module is then for parents to learn about the location of their closest facility and team of health workers, and how to get in contact with them. Parents and facilitators also discuss mobile clinics and their services, as well as home-visit health programmes.

- Education for all: emphasizes the importance of supporting children’s school attendance from an early age as well as keeping them engaged in their learning, and providing support with their homework. Messages include the benefit of reading with children for 10 minutes a day, and asking them questions. If a parent cannot read, the participation of an older sibling is recommended to support both the reading itself and the process of acquiring strategies for reading with children. Although strengthening parents’ own reading and writing skills is not one of the main goals of the programme, this module helps them acquire skills to support their children’s development and school attainment, e.g. understanding child development milestones, early stimulation, pedagogical games, nutrition, and positive forms of discipline. A specific section on how to support children’s education is part of the module.

- Youth issues: looks at how best to discuss sexual and reproductive health with adolescents, to prepare them for the future.

Teaching and Learning: Approaches and Methodologies

Each module is covered in a two-hour parenting education session; these are held every three months (projected roll-out dates can be found in the table below). Each session is led by a local team composed of trained community workers. Interactive learning methods are used such as role-play, demonstrations, and small group discussions, together with information, education and communication (IEC) materials, e.g. flip charts, posters, videos, and flyers. These materials have been developed by Ba Futuru NGO and Rain Barrel Communications, who were hired by UNICEF Timor-Leste. This ensures that the community sessions are contextualized, engaging, interesting and valuable.

Recruitment and Training of Facilitators

The training of facilitators includes a national Training of Trainers (TOT) programme and training at suku level.

TOT programme for Trainer-Mentors The TOT training programme comprised a four-day workshop held in Dili (Timor-Leste’s capital). Participants included MSS staff from administrative posts (two participants each) from the cities of Ermera and Viqueque as well as non-MSS personnel who were identified as potential future trainer-mentors through the preparation and training process. In total, 28 participants attended the workshop (15 men and 13 women).

Topics covered included the concept and structure of the programme, facilitation strategies and tips, and the four modules included in the first implementation manual (general parenting, early stimulation, child protection and positive discipline).

Ba Futuru facilitators were extensively involved in workshop preparations, including the group and individual review of training materials, role-play sessions in TOT training, and group feedback sessions. These facilitators were also in charge of maintaining and extending communication between those at the national and local administrative levels, in the phase between initial coordination visits and induction training.

Training at the suku level Training sessions in municipalities (suku) for future facilitators of the parenting education sessions were conducted by TOT participants, with the support of advanced facilitators from Ba Futuru. These sessions were held over a two-day period in Ermera and Viqueque. On average, two or three people from each suku, selected by the village chiefs (xefe suku) through workshops facilitated by MSS, were invited. In total, 51 participants attended the training sessions.

Topics covered included programme structure, facilitation skills and the first two modules (general parenting and early stimulation).

Mentor-trainers and participants gave daily feedback on the quality and effectiveness of the training. Ba Futuru facilitators also observed parenting education sessions, took notes about the session facilitators’ ability to present information, led activities, enabled discussion, and spoke with community leaders before and after the sessions.

Suku-level facilitators work as volunteers and only receive a small amount of compensation for travel expenses (US$5 per volunteer for each session led).

Enrolment of Learners

Initially, the programme aimed to reach exclusively those parents served by the Bolsa da Mãe programme. However, as the Hametin Família programme has expanded, MSS has managed to reach a wider community of vulnerable households with children up to the age of 18.

Before the implementation at community level, village chiefs (xefe suku) shared information about the programme and upcoming pilot schemes within their villages. Public announcements and personal invitations were also used to inform parents.

Eleven parenting education sessions were held at suku administrative offices, accommodating a total of 609 parents in two pilot municipalities. The number of participants in each session varied across sukus – from a minimum of 21 participants to a maximum of 88 participants per session.

Monitoring and Evaluation

The monitoring process comprises monthly reports sent from village level to the administrative post level, quarterly reports from administrative post level to the municipality level, and biannual reports from municipalities to the national level. At the national level a Programme Working Group was established to provide support to both MSS trainers and local level trainers, and to oversee the programme, making adjustments where necessary and planning for the next phase.

Ba Futuru was at first responsible for supervising training at both suku level and for the parenting education sessions; this was designed to provide support and mentoring for newly instructed trainer-mentors and community level facilitators.

An evaluation framework was designed, based on the results of a comprehensive KAP survey. In alignment with the baseline survey conducted in 2015, a programme review will be carried out in 2017 and an impact evaluation in 2019 (after the end of the programme) in the two municipalities in which the programme has been implemented. In addition, these surveys will also be conducted in two other control municipalities (Bazartete and Iliomar) where the programme has not been implemented. This allows for comparison between the groups, and a review of the impact of the programme’s interventions.

Programme Impact and Challenges

Impact and Achievements

According to the programme evaluation conducted in March 2016, 11 community sessions were carried out in villages following training at suku level. Sessions were attended by 609 parents across two pilot municipalities. As of August 2016, this programme has reached parents and caregivers in 15 villages within the districts of Ermera and Viqueque. It has provided training for an average of 70 parents in each village. While the evaluation of parent training is ongoing, the evaluation of the TOT, and training activities at suku level, were completed with the following results:

TOT participants have reported increased knowledge of early stimulation (54 per cent), child protection (20 per cent), alternative positive discipline (62 per cent), and knowledge of the programme. Participants of the training at suku level have reported increased knowledge of children’s needs and babies’ cognitive development.

The pilot programme also won enthusiasm from community members who were interested in attending the sessions, and the teaching materials were well received by the participants.

Participant’s Testimony

Through this programme we learnt how to support our children’s development as they grow… We also had the opportunity to share this information with those in the community. But the time was too short for us to learn well, because if we’re going to share this information we need to study and practise a lot. It’s because of this that, if possible, this information should be shared not only in Ermera but also with communities all across Timor-Leste. Napolito C. Madeira, 23, training participant, representative of the Group Dejukdil [Catholic youth group], Suku Railaco Leten, Railaco, Ermera

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Some challenges were identified in a recent evaluation. They are:

- Inadequate facilitation skills of trainer-mentors. Facilitators need the skills to ensure that sessions are interactive and participatory. Some communities elected facilitators whom they trusted, but who might not have had adequate facilitation skills. In Ermera, some facilitators had difficulty applying what they had learned in training sessions to facilitation practices, which sometimes led to sessions running overtime.

- Low level of parents’ consistent participation, because of the long walk from remote rural villages to the training centre. Moreover, participants were surprised not to be offered snacks/coffee during the parenting session, as this is a cultural custom when people get together. This has been addressed and now snacks are provided.

- Low retention of facilitators. Facilitators are normally involved in other work in the village while volunteering for the scheme, and do not get paid.

- Uncertainties about the availability of funding for future evaluation work, despite ongoing fundraising activities.

Several lessons were learned:

- The duration of training sessions – both TOT and induction training – can be extended to ensure that facilitators have adequate knowledge. In addition, further attention should be paid to the selection of facilitators to ensure the quality of their work.

- The existing human resources in the communities can be mobilized to support the implementation of the programme.

- Parents who had been reluctant to engage with some of the programme’s content, such as discipline and paternal involvement, became more interested and more willing to discuss these topics after they were explained in greater depth.

- It is crucial that all governmental agents are actively involved and fully committed to the implementation of the programme. Local authorities have been interested and involved in the programme, which has had a positive impact on the engagement of parents.

- The attendance of a few fathers generated the interest of other men within the community, and encouraged them to participate.

- Using the local language is beneficial for the participants. In Viqueque, where Tetum is not widely spoken, parenting education sessions have been mainly led in local languages which enabled participants to understand and join in with activities. While the material is developed in the official language, facilitators try to strengthen learners’ understanding of concepts and ideas using local dialects.

- The implementation manuals can be improved by shortening explanations, and simplifying or changing words that are too technical for everyday use.

Next Steps and Sustainability

Hametin Família is designed to complement and work alongside existing programmes. The providers are currently in the process of identifying entry points to allow the course to be offered to as many beneficiaries as possible. Examples of planned future activities include the training of child protection network members in each municipality, as well as NGOs and churches workers, so they can make use of the Hametin Família modules within their programmes. Another entry point currently under consideration is collaboration with existing UNESCO-supported community learning centres, by training their facilitators to use Hametin Família modules with their community groups. Ideally the modules will also be used by existing adult literacy programmes.

The MSS has included this programme as part of the Child and Family Welfare Policy Implementation, under which Timor-Leste’s government intends to shift the approach on child abuse from reactive responses to preventative measures. It does so by engaging families and communities, and strengthening the programme through their involvement. Having people from village level trained in the key areas of parenting skills allows that knowledge to be retained and shared within the community in various ongoing ways. In the future, MSS plans to expand the programme to 87 villages, to reach up to 10,000 parents by 2018.

Sources

- National Statistics Directorate (NSD) [Timor-Leste] 2010. Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey 2009-10. Dili, Timor-Leste: NSD [Timor- Leste] and ICF Macro. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR235/FR235.pdf (22 August 2016).

- Taylor-Leech, K. 2008. Language and identity in East Timor: The discourses of nation building. Language Problems & Language Planning 32:2 (2008). John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.153–180. Available from: http://www.cultura.gov.tl/sites/default/files/KTLeech_Language_and_identity_in_east_timor_2008.pdf (4 November 2016).

- UNESCO 2015. Education for All 2015 National Review Report: Timor‐Leste. Available from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002298/229880E.pdf (22 August 2016).

- UNICEF 2012. Annual Report 2012 for Timor-Leste, EAPRO. UNICEF. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Timor-Leste_COAR_2012.pdf (22 August 2016).

- UNICEF 2013. Annual Report 2012 for Timor-Leste. UNICEF. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Timor-Leste_COAR_2013.pdf (2 December 2016).

- UNICEF 2015. Quality Education. UNICEF. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/timorleste/Education(1).pdf (22 August 2016).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics(UIS) 2015. Available from http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/tl?theme=education-and-literacy (6 June 2017).

- Materials prepared by Ba Futuru and Rain Barrel Communications for UNICEF Timor-Leste (unpublished)

- Ba Futuru and Rain Barrel Communications 2015. Design and Pilot of a Parenting Programme to Improve Developmental Outcomes for Disadvantaged Children and Adolescents in Timor-Leste – Phase II. Inception report.

- Ba Futuru and Rain Barrel Communications 2016. Design and Pilot of a Parenting Programme to Improve Developmental Outcomes for Disadvantaged Children and Adolescents in Timor-Leste – Phase II. Research Report Study of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Towards Ten Key Focus Areas of Parenting in Timor-Leste.

- Ba Futuru and Rain Barrel Communications 2016. Design and Pilot of a Parenting Programme to Improve Developmental Outcomes for Disadvantaged Children and Adolescents in Timor-Leste – Phase II. Pilot assessment report.

Contact

Florencio Pina Dias Gonzaga

Director of National Directorate for Ministry of Social Solidarity

Avenida Bemori

Dili

Timor Leste

Email: flo.gonzaga2002@gmail.com

Tel: +670 7825 8649