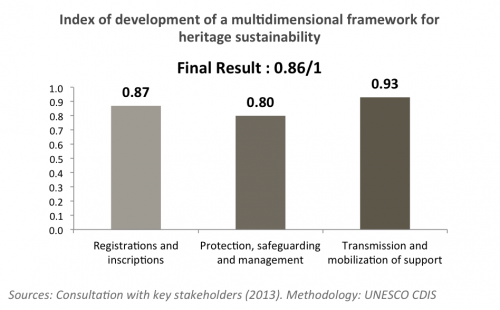

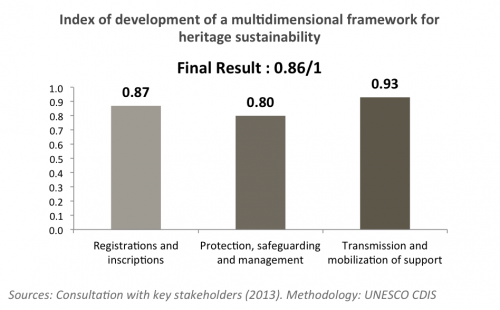

22 HERITAGE SUSTAINABILITY: 0.86/1 (2014)

Colombia’s result of 0.86/1 is reflective of the high level of priority given to the protection, safeguarding and promotion of heritage sustainability by Colombian authorities. The policy, institutional and management development regarding heritage has been significant in recent years. While many public efforts are dedicated to registrations and inscriptions, conservation and management, capacity-building, social appropriation and community involvement and raising-awareness, select persisting gaps call for additional actions to improve this multidimensional framework.

Colombia scored 0.87/1 for registration and inscriptions, indicating that authorities’ efforts have resulted in many up-to-date national and international registrations and inscriptions of Colombian sites and elements of tangible and intangible heritage. The national inventory of cultural heritage of Colombia is the list of Properties of Cultural Interest (BIC), which is updated at least once a year. The BICs include heritage assets reported prior to the adoption of the Cultural Heritage Law 1185 in 2008, as well as archaeological heritage sites declared after the issuance of this law. Currently there are 1092 BICs. Government efforts have also resulted in the successful recognition of 6 cultural heritage sites as World Heritage. The national inventory of intangible heritage of Colombia is recorded on the Representative List of Intangible Heritage -LRPCI. Fifteen manifestations of intangible heritage have been declared and recorded on this list, eight of which are part of the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Colombia scored 0.80/1 for the protection, safeguarding and management of heritage, indicating that there are several well-defined policies and measures, but select gaps persist. The Cultural Heritage Law 1185 of 2008 is now the legislative support of cultural heritage policy in Colombia. This law establishes concepts and contemporary models of management, protection, conservation, recovery, safeguarding, sustainability and dissemination of tangible and intangible heritage. It establishes an institutional structure in which the various levels of government administration work together to fulfil these functions, alongside of communities. The National System of Cultural Heritage is the body that articulates and decentralizes this structure and establishes mechanisms for participation and management. Through this system, the National Heritage Council as well as the Departmental and District Heritage Councils participate and interact with national and local government entities. These institutional and management developments are not yet sufficient as gaps still remain in some areas. One challenge that remains is a need for increased budgetary allocation for the protection and promotion of heritage, requiring the efforts of not only the national central State but also local governments, and in some cases the private sector. Moreover, although major recovery efforts of historic centers have been launched, additional investment and management is required for more complete revitalization. Other challenges concern improving management and safeguarding capabilities regarding intangible heritage celebrations. The intangible heritage of indigenous groups and Afro-descendants is at risk in some regions of Colombia due to inadequate skills in these areas. Finally, although Colombia is party to the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and has adopted national legislation to ensure its application, no specific capacity building and training programmes for the armed forces regarding the protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict have been implemented in the last 3 years. Another gap consists of the lack of systematic inclusion of local communities in heritage site management committees, although authorities do recognize that local communities are to be included in registry and inventorying processes. Finally, major heritage sites do not have Disaster Risk Management plans. However, following the climate disaster of the 2010-2011 Niña weather phenomenon, exceptional measures were taken and the Ministry of Culture launched an initiative to repair cultural infrastructures that were affected. 85 buildings were rehabilitated in 12 departments and 60 municipalities.

Colombia scored 0.93/1 for the transmission and mobilization of support, which reflects the tremendous efforts taken to raise awareness of heritage’s value and its threats, as well as efforts to involve all actors in the safeguarding of heritage. The support and involvement of the private sector and civil society in the protection, conservation and promotion of cultural heritage is fostered through the Special Management and Protection Plans of Heritage Properties and the Special Plans for the Safeguarding of Intangible Heritage. The 2008 Cultural Heritage Law created these plans to establish activities relevant to identification, documentation, research, preservation, protection, promotion, enhancement, transmission and revitalization; and to include in these activities, rigorous processes of consultation and coordination between communities, bodies of the State and participation mechanisms. Regarding the raising of awareness, in addition to differential pricing, measures include programmes to promote the sustainability of natural heritage amongst school age children. Further efforts to improve awareness could be made by increasing the signage at World Heritage sites and at major national cultural heritage sites inscribed in national registries, as no normative framework yet exists regarding the clear identification of such sites for visitors.