Programme Overview

| Programme Title | National Literacy Programme implemented by all sectoral stakeholders supported by the UNESCO-PEER project |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | Literacy Department, formerly the National Literacy Service |

| Funding | The Burundi Government is the principal source of funding |

| Programme Partners | UNESCO, religious denominations, local and international NGOs |

| Date of Inception | 1989 |

Country Context and Background

Burundi is one of the poorest nations on the planet, ranking 178th out of 186 on the UNDP Human Development Index (UNDP, 2013). Burundi is still recovering from the aftermath of the civil war (1993-2005) with serious infrastructure deficiencies in power, transport and communications (AFDB, 2009). Around 90% of the population lives in rural areas, a large number of these living on subsistence farming. Only 2% of the population in Burundi have access to electricity (AFDB, 2009).

Burundi is reported to have an average adult literacy rate of 67%, with 7.1 % of adults over the age of 25 having received a secondary education (UNDP, 2013). In numerical terms, this means that over 1.5 million people are lacking basic literacy skills and just over 210,000 people have received a secondary education. The socio-political crisis of 1993 had an impact on primary education rates with at least a third of all provinces (6 out of 17) recording a 22% drop in net enrollment rates which stood at 52% pre-crisis (UNESCO, 2000). In spite of this, Burundi has made great strides in meeting universal primary education. With a net primary enrollment rate of 37% in 1998, this increased to 53% in 2002 and 77% in 2011 with relatively little disparity now being reported between boys and girls (UIS, 2013; UNESCO IBE, 2010).

Programme Overview

The organization overseeing literacy in Burundi is the Literacy Department, established by ministerial order on 15 May 1991. Its main aim is to provide young people and adults with little or no literacy skills with suitable training designed to meet their basic educational needs, while also reducing the overall illiteracy rate. This includes helping them to acquire reading, writing, numeracy and self-development skills as well as encouraging the newly literate and current learners to form community self-promotion groups which permit the learners to develop on an individual level as well as a group level keeping in mind the context and environment.

The focus is not only on obtaining initial literacy skills, but also on maintaining them and developing them further. Literacy training themes focus on local issues and everyday living with an emphasis on shouldering responsibilities and developing local income-generating activities.

The Literacy Department is divided into four different units, each caring for a different aspect of the programme. It is structured in the following way:

Aims and Objectives

- Creating a literate environment conducive to self-development

- Establishing a post-literacy and continuing education system for poverty reduction

- Helping to establish a social climate conducive to peaceful coexistence and mutual trust through education for peace, human rights and democracy

- Mobilizing the local people and authorities to join and/or support literacy programmes

The first objective aims not only to teach the three R’s (reading, writing and arithmetic) but to create an environment that is conducive to literacy improvement as well as individual self-improvement. The next objective seeks to maintain newly acquired literacy skills and develop them further. Through a system which makes reading books available, known as suitcase libraries, books can be borrowed from facilitators and returned as required. Books cover everyday themes and subjects studied in class, permitting these new readers to further their literacy skills while expanding their knowledge and putting into practice what they have learned.

The third objective is in line with the recovery the country is still going through from the period of civil war they experienced. A climate of suspicion and distrust still exists in the country. Through the programme, designed to welcome all people regardless of their gender, ethnic group, religion and region, participants learn to work through relations and ultimately full reconciliation. During literacy classes, this often takes the form of group work overseen by the facilitator.

The last objective aims to bring on board the local authorities and create a reciprocal environment. The authorities cannot achieve sustainable development if the populations under their authority remain ignorant, and so the literacy programme builds the local authorities’ awareness of the merits of including literacy as one of the components of development plans.

Programme Implementation

Teaching – Learning Approaches and Methodologies

Literacy courses are held twice per week for two hours per day or in other settings, but always four hours per week. The meeting times and days are agreed upon by the learners themselves in collaboration with their facilitator, as the schedule takes household duties, growing seasons, harvests and other matters into account. Each course lasts three months or slightly longer, depending on the facilitators and learners availability. This also means that learners may attend three courses in a year. The language of instruction is in the learners’ mother tongue, notably Kirundi.

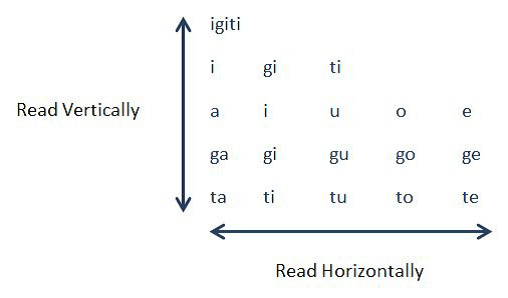

The method used for learning to read and write is based on the Freirean principles, with learners actively participating in their own learning. In general, classes begin with a poster-problem posed by the literacy worker. The poster typically depicts a theme selected to evoke a local problem to which the population must be sensitized. A discussion is then started with the learners around the poster. The discussion ends with a keyword being selected for its evocativeness and its ability to generate a wide range of other words. The keyword is then broken down into syllables which are then used to form families of syllables. For each syllable, the syllabic families are written horizontally in the same consonant-vowel association order. The learners are requested to read them horizontally and vertically in order to hear the effect of each vowel on the same consonant and vice-versa. It can be illustrated in this way, with the example of the word igiti (tree):

Next, the learners are requested to make other words from the syllabic families and to read out the new words composed, adding to their newly acquired skills before moving on to various exercises and then learning to read. Reading is introduced gradually from the first lessons, and the principle of progressing from simple to complex content is observed.

In order to provide a practical learning content, arithmetic is included in the reading and writing manual and the lessons cover reading and writing figures from 0 to 1,000,000, learning the different measurements (capacity, weight, length, volume and area) and mastering basic addition, division and subtraction.

Programme content (curriculum)

Literacy training themes relate to everyday life, agriculture, livestock farming, nutrition, decent housing, health, reproductive health, hygiene, savings, trades, human rights in general with a particular emphasis on children’s and women’s rights, and the ideals of peace, such as tolerance and peaceful coexistence.

The post-literacy programme provides the newly literate with the opportunity to maintain and develop acquired skills, gain knowledge to improve their living conditions and shoulder responsibilities in local development activities.

In regard to literacy curricula, the Department has produced, proposed and provided the syllabi to all literacy stakeholders. Various materials are used, including, teacher guides, booklets for learners, reading booklets, problem posters, blackboards, chalk, exercise books and pens. Furthermore, the Department has developed and produced post-literacy reading booklets.

The material was developed during workshops by Literacy Department’s curriculum designers. The five primary tasks below are involved in developing the teaching materials:

- designing and producing picture flash cards. For example, if the key word is water, a scene from everyday life portraying the effort of carrying water, the difference between drinking water and polluted water or similar scenes, is drawn on the card

- writing a caption, prompted by a drawing, for subsequent use on a poster

- selecting learner-booklet content, such as keywords, for work on letters, groups of letters, syllables, words (with a simplified design)

- drafting the instruction sheet which will guide the literacy facilitator and may be included in the published literacy teacher’s handbook

The team that designs new teaching materials must pre-test its new ideas in a context similar to that of the target group taking certain prerequisites into account. The pre-test results are instrumental in assessing the relevance and effectiveness of the material and in decisions regarding pre-print and pre-distribution improvements.

Recruitment and Training of Facilitators

The facilitators are generally paid or volunteers. They receive an initial training in course leadership, functional literacy and post-literacy techniques. The average learner-facilitator ratio is 35 to 1. Civil servants are paid by the Government, depending on their status or contract, while volunteer literacy workers receive a token amount once a year on 8 September, during the International Literacy Day celebrations. Teaching adults is not the same as teaching children and so facilitators require training to meet these needs. Technical support is given and training in the use of literacy curricula and teaching tools.

In the training area, the Department seeks funds from donors, particularly UNICEF and UNESCO, in order to train the literacy teachers and buy the teaching and reading materials for distribution to the stakeholders. Many partners, including NGOs, associations and religious entities (around 35), received assistance from the Department, between 2003 and 2011, in the form of training (for around 3,500 literacy workers) and the provision of tables, exercise books, pens, chalk and post-literacy reading booklets. It should be noted that literacy and post-literacy teaching materials are given to the stakeholders free of charge.

Furthermore, there are visits to the provinces and communes to raise the awareness of the local authorities and encourage their involvement in literacy programmes. In the area of training, since 1996 the Department has organized workshops in order to boost the managers’, workers’ and literacy teachers’ knowledge of functional literacy and post-literacy techniques and methodology. As to the training of managers and workers, 200 trainers have attended practical literacy and post-literacy workshops and regarding the training of literacy workers, more than 5,000 literacy workers have been trained for the National Literacy Programme.

Enrolment of Learners

The main target groups are adults above the age of 15, out-of-school youth, women and girls, minorities (the Batwa), returnees and demobilized combatants. On average there are 35 learners per group.The programme is currently running in 950 literacy centres.

With regard to the raising of awareness, International Literacy Day (8 September), celebrated by the government every year since 1990, proves to be a special opportunity to mobilize decision makers at all levels and the population to take part in literacy programmes. On that occasion, awards are given in recognition to the most outstanding volunteer literacy workers and the newly literate from the various public and private centres are presented with their certificates.

Assessment of learning outcomes

The programme has been accredited by all stakeholders and is used by non-governmental organizations (local and international) active in this field. Literacy students are tested at the end of the programme and those receiving a score of 50% and above receive certificates. These are recognised by the government, but do not have an equivalent level to a primary education. Between 2004 and 2011 the Literacy Department issued 185,754 certificates to the newly literate.

Monitoring and Evaluation

For the purposes of coordinating and managing activities, the Literacy Department has appointed provincial literacy coordinators and has annual meetings with partners to ensure programme consistency with partners working on activities complementarily rather than competitively. The provincial literacy coordinators oversee literacy activities in the various provincial communes and send quarterly and annual reports to the director of the Literacy Department.

In the communes, there are local managers who supervise literacy and post-literacy activities in the various public and private centres. They draft quarterly and annual reports for submission to the provincial literacy coordinator. Visits are made to the literacy centres to supervise and monitor the facilitators as well as the good implementation and progress of the programme.

Programme Impact and challenges

Impact and achievements

Since 2004, the Literacy Department has been recording the literacy centres’ certificate-winning students by province (Coordination) and by year. As a result, between 2004 and 2011, the Department has issued 185,754 certificates to the newly literate.

A project is under way to evaluate the impact of the programme, but this is still awaiting funding from financial backers.

Challenges and lessons learned

Several challenges can be noted since the implementation of this programme. The first is a lack of involvement of rank-and-file officials along with a lack of resources. Low enrolment and participation by the target population in the literacy programme has also been observed. A lack of post-literacy activities to consolidate learning achievement led to the creation of the post-literacy unit, to counteract this situation. Tasks assigned to the Literacy Department have been inefficiently coordinated, largely due to insufficient resources. There is also a high drop-out rate among participants before the end of the programme.

Sustainability

The programme has been well received by the participants, however, obtaining adequate funding makes it difficult to judge its full sustainability. It has already been replicated in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo, under the UNESCO-PEER project implemented in Burundi.

Sources

- UNDP (2013) Human Development Report 2013

- AFDB (2009) An Infrastructure Action Plan for Burundi - Accelerating Regional Integration

- UNESCO (2000) The Education for All 2000 Assessment

- UNESCO IBE (2010) World Data on Education – Burundi

- UIS (2013) Education profile - Burundi

Contact details

Dominique Ndikumana

Chief executive officer / Director of the Literacy Department, Ministry of Education : Ministry of Basic and Secondary Teaching, Vocational Teaching, Professional Training and Literacy (Ministère de l’Enseignement de Base et Secondaire, de l’Enseignement des Métiers, de la Formation professionnelle et de l’Alphabétisation)

B.P.287 BUJUMBURA, Burundi

Telephone / Fax: (257) 22234374

(257)22231261

Mobile: (257)79304875

Email:User: dominique_ndikumana

Host: (at) yahoo.fr

Last update: 10 June 2014