Programme Overview

| Programme Title | We Love Reading - “A Library in Every Neighbourhood” |

|---|---|

| Implementing Organization | Taghyeer (national NGO) |

| Language of Instruction | Arabic and English |

| Funding | Synergos; Ministry of Culture Jordan; Reliance; ARAMEX; US Embassy Jordan; USAID ECODIT; Middle Eastern Partnership Initiative; US foundation Fetzer; Shoman Foundation; Microsoft; LitWorld; Yale University; and publishers Scholastic and Dar Al Manhal. |

| Programme Partners | Partners in Jordan: Hashemite University; Amman Municipality; Injaz‐Junior Achievement; Reliance Co.; Ruwwad Community Development Organization; Dar Al Manhal (publisher); Business Development Center; Drive to Read; Women Microfund; Arabic book Program/US embassy Jordan; Children’s Museum Jordan; Zaha Cultural Center; Queen Rania Teachers Academy; authors Abeer Taher and Taghreed Najjar. International Partners: Mother Child Education Foundation (ACEV) and Hüsnü Özyeğin Foundation, Turkey; New Haven Public Library, New Haven, CT USA; World Innovation Summit in Education, Qatar; Mercy Corps; Save the Children; Yale University; Neurosuite Clinic, University of Chicago; Columbia University; International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY); Global Education Forum; International Reading Association; Scholastic (publisher); Clinton Global Initiative; Thomson Reuter Trust. |

| Annual Programme Costs | $100,000 Annual programme cost per learner: $50 |

| Date of Inception | February 2006 – ongoing |

Country Context and Background

Because of the investment in social development programmes concerning family planning, healthcare and education, Jordan has experienced comparatively rapid economic development. In 2012 the kingdom generated a GDP per capita of $6,037, placing it in the middle of World Bank income rankings.

Up to 2003 literacy levels in Jordan consistently improved. Since then the situation has become less stable. The lowest number of illiterate adults (273,873) was recorded in 2007 and the highest in 2010 (286,602), while, from 2010 to 2011, the number of illiterate adults decreased notably (to 163,948) (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). One reason Jordan has the highest level of literacy in the Arab world is the commitment of the Jordanian government to resolutely address the country’s literacy challenges, which is why the Adult Learning and illiteracy Elimination Programme (ALIEP) was launched in 1952.

The country is a refuge for people fleeing surrounding countries, which means that the number of illiterate adults increases parallel to the rising numbers of refugees. Education is compulsory in Jordan for children aged between six and 15, but, as recent examples show, reading is not equally valued in all Arab countries. According to the Arabia News, Arab adults, on average, read only half a page per year for pleasure. This alarmingly low figure corresponds to the results of UNESCO reports of 1991 and 2005, as well as the US Working Paper for the 2004 G8 Summit, which stated that Arab readers average six minutes reading in a whole year. Because of the relatively high literacy rate in Jordan it is unlikely that insufficient reading skills are the reason for these survey results. It is more likely that the lack of interest in reading is due to a lack of reading practice and a failure to cultivate reading habits. Evidence shows that reading aloud is key in fostering the pleasure of reading (Trelease, 2013). Jordanian society has yet to realise that a fully literate society is essential for economic development and social integration.

The Organisation

Taghyeer is a Jordanian non-governmental organisation that, through various programmes, works to develop, train and encourage women, young people and children in the fields of education, particularly literacy, entrepreneurship, and health. The aim is to encourage them to change their attitudes and become more responsible citizens with greater control of their lives. The model of We Love Reading (WLR) was developed in Jordan and has since spread out to other countries, many of them in the Arab world. Rana Dajani, the founder of this programme, is an associate professor and former Director of the Center for Studies at the Hashemite University of Jordan.

Programme Overview

WLR aims to have a positive impact on children, adolescents and their families throughout Jordan and the Arab world by creating a generation of children who love reading books. The programme seeks to achieve this through the establishment of a library in every neighbourhood in Jordan, supported by women trained by Taghyeer in reading aloud. The women read to children aged between four and 10 years old in their local communities, utilising age-appropriate reading material. WLR also seeks to promote the value of reading more widely, changing attitudes and encouraging volunteering among older age groups.

The programme’s target groups are children, adolescents (aged 15 to 24 years), adults, families, women and girls, though the organisation also addresses the needs of a great number of minority groups and people in need. These can be out-of-school children, unemployed and poor people, or minorities such as ethnic groups, migrants and nomads, as well as refugees, religious communities and prisoners.

The organisation considers reading to be a shared value and a means to achieve the common goal of mobilising adults (as reading volunteers) and young children (as participants in reading sessions) and making them realise that they are responsible for themselves. Therefore, the approach is to invest in building the capacity of the younger generation to build a foundation for further personal development. We Love Reading runs a web page, which functions as a platform to support the dissemination of the model to other regions (http://www.welovereading.org/).

Aims and Objectives

Main aim:

- Bring about social change through reading.

Objectives:

- Create and foster a love of reading, primarily among the younger generation;

- Change attitudes and promote the importance of reading;

- Support a gradual and natural development of women’s leadership within the community;

- Substitute the role of parents in reading to their children; and

- Introduce and sustain the concept of volunteerism among young people.

Programme Implementation

Introduction

The “library” as a learning environment is established in an existing and commonly used public space. This location should be easily accessible for neighbourhood children, which is why mosques and other community centres were selected to be appropriate institutions for the reading sessions. The book collection consists of as few or as many books as can be gathered through donations from individuals or organisations. The children love to hear the same story over and over again. A read-aloud session is held every weekend and afterwards the books are given to the children to read at home. Later, the books are returned so that other children can borrow them.

Mothers have become involved in WLR. They support the readers and attend reading sessions in the mosque as well as reading to their children at home. Some children drag their parents out of bed at the weekend to attend one of the storytelling sessions, helping stimulate a positive attitude to reading among parents.

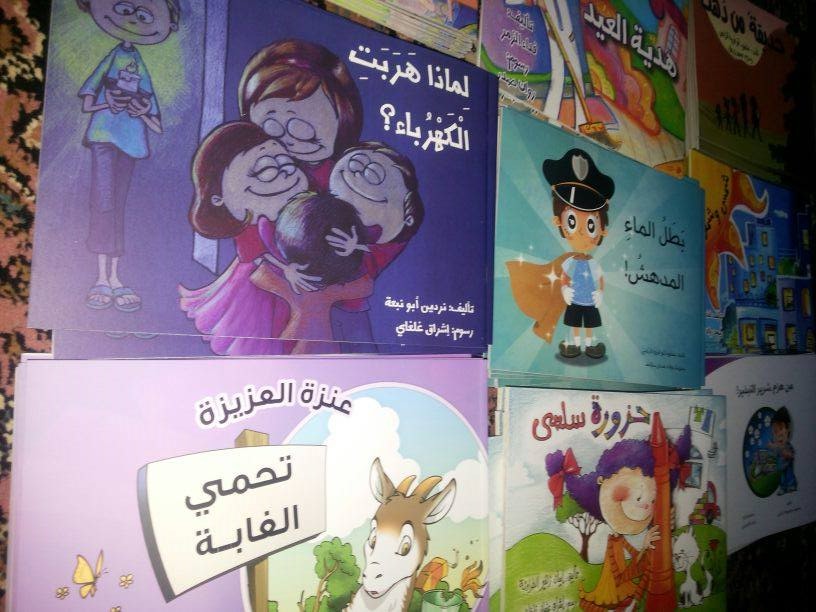

Books Read to the Children

The books read to the children are written in their mother tongue and reflect the cultural background of the children. This means that the stories are easy to understand and show the children how to build positive attitudes and apply best practices in their everyday life. It is also hoped that these lessons are transmitted to their parents and the community. This can happen, for example, if a mother reads a book taken home by her son about a boy who conserves water. When the mother does not conserve water the boy will remind her that she has just read him a story that shows she should conserve water. The books are all age-appropriate and fictional.

Recent research shows that adults who read literary fiction are more empathetic than those who read non-fiction, or who do not read at all (Bal and Veltkamp, 2013; Kid and Castano, 2013).

In addition to reading aloud, the children perform activities related to the stories in the book. In partnership with the U.S. non-profit organisation ECODIT, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), more stories about the environment and the conservation of water and energy are being developed for the reading sessions in Jordan.

Recruitment and Training of Volunteers

There are several ways of engaging as a volunteer for WLR, such as becoming a reader, advocating for reading, or volunteering to organise the library or do other outreach work. Reading to their own children involves parents as well. We consider them as volunteers if they attend the WLR read-aloud sessions and read to their children the books they bring home.

Reaching the Reading Volunteers

The first step in the process is to recruit individuals (they may be male or female and of any age) who meet the requirements. They are recruited through word of mouth, youth organisations, women’s organisations, the programme website, social media, public events, and so on.

Requirements of the Reading Volunteers

The volunteers recruited do not have to be highly educated, but they do have to love children and reading and be willing and motivated to volunteer. This implies an ability to maintain a responsible, passionate and dedicated attitude towards their work. They also have to be part of the same neighbourhood as the families, so that they are trusted and welcome.

Content of the Training

Taghyeer is in charge of the training for the volunteers, which is offered three times per year and lasts for two days. The focus of the training is on capacity-building in multiple areas, including teaching, communication, confidence building and soft skills. The participants also learn about time management, planning and financing. They are instructed in how to set up and run libraries, as well as in how to read aloud.

Specific themes covered by the leadership training include basic literacy and numeracy skills, advanced literacy, life skills, family literacy, intergenerational learning and gender, as well as supporting literate environments and sustainable community development. A course on creative thinking and time management encourages open-mindedness to other perspectives and outlooks on life. This includes learning how to formulate persuasive arguments to defend a perspective and how to internalise criticism positively and contribute to debates conducted during the training.

Training Methodologies

A self-developed curriculum and manual are used as guidelines for the facilitators of the leadership training. The volunteers are trained by the programme initiator, together with a professional trainer specialising in reading aloud.

The training is highly interactive and includes debates and presentations dealing with the leadership role of the woman in the community, as well as visual and breathing exercises. The participants practice reading aloud in front of each other. This is supported by training in public speaking skills, eye contact, control of the voice and body language. The women are invited to work in teams, to share perspectives, opinions and their needs in working together to find solutions to challenges. Empathy, respect and acceptance are core values transmitted in the training. They enable the women to teach respectful and inclusive approaches to discussion. For example, if a person disagrees with somebody, he or she can be encouraged to appreciate the background of the counterpart and respect their different opinions. This attitude fosters inclusion and acceptance among the trainees who, in turn, become role models for others.

A multiplier effect is secured through the peer-to-peer training as women leaders, who have received the training already, are asked to pass on their knowledge and teach other women. This is also how new volunteers are approached. This fairly efficient process means that costs are kept low and more librarians can be trained.

After implementing the model over a three-month period the readers are assessed through personal reflections and diaries shared during a one-day meeting. At the end of the training they receive a certificate. No test is conducted, either before or after selecting eligible readers.

Training Fees

Taghyeer used to conduct free trainings, but not every person trained decided to become a librarian in the end. In order to identify those individuals who are more dedicated, the organisation started to charge a fee for the training. This amount could be spent on improving the efficiency of the programme, which also led to better libraries in the long run.

Monitoring and Evaluation of the Programme

Every reader has to fill in a survey, which is conducted annually. It includes statistics on the number of participants, disaggregated by gender, the amount of stories read, and the frequency and duration of the sessions.

The programme’s impact on behavioral change is currently being assessed in collaboration with USAID and the University of Chicago, The progress is locally, regionally and internationally monitored by a follow-up assessment as well as by reports from the volunteer readers, write a diary and share their successes and challenges on Facebook (https://ar-ar.facebook.com/WLReading). Their feedback during and after the training is incorporated into the training and used to improve the process and remove irrelevant parts, helping design a simpler and more effective programme.

The impact of the programme is assessed by qualitative studies, which include focus group discussions and interviews with parents, children and readers. WLR members organise visits to the libraries as well, where they take pictures, interview the volunteers, the parents and the children. At the moment, WLR is developing a monitoring and evaluation platform of the exisiting libraries in collaboration with Columbia Unviersity, USA.

With the support of an educational specialist from the Hashemite University, WLR has produced a report that describes the impact of reading on behavioural change in children. Another study shows an 84% improvement in the leadership and social entrepreneurship skills of adults who have participated in the training for and implementation of the WLR library in their neighbourhood. WLR is currently undertaking a study on the effect of reading on empathy in children.

There have been no qualitative evaluations of the improvement of literacy skills among participants. WLR measures its success in terms of how may children it engages in reading groups. Through individual interviews with children, WLR found out that the sessions have a long-lasting impact on young people and influence their decision-making throughout adulthood.

Programme Impact and Challenges

Impact and Achievements

International Recognition

The programme has spread out to 14 countries worldwide (among them Azerbaijan, Egypt, Germany, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Malaysia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and United Arab Emirates) and has reached 100,000 individuals throughout the world.

Impact on Children

The participating children developed their own culture of literacy among themselves, which means they discuss and recommend books and authors to each other. They continue to read and parents state that their children exhibit improved self-confidence and academic skills, and are even likely to buy and read books rather than toys. Most of the children recognise and are able to name authors without the help of their parents. The children are encouraged to deploy the reading skills they acquire in their everyday life afterwards. Even older children who do not attend the sessions anymore remain readers. The programme also stimulates creativity in children, especially girls.

WLR distributed copies of English books to different neighbourhoods. In those areas in Jordan without libraries, where children had not been read to on a routine bases, children did not read the distributed books, because they felt intimidated and considered reading a burden. In contrast, in neighbourhoods where libraries were established, children were enthusiastically reading the books, an indication of a successful programme.

Impact on Individuals and the Community

Reading in Jordan has traditionally been considered as boring or a waste of time outside academic or religious contexts. WLR is showing people that reading is valuable, even as an activity in leisure time. As time passes, the community also starts to invest in the book collection, to foster book ownership and to take responsibility for the library.

In Jordan alone, WLR has trained 700 women, created 300 libraries and had a direct impact on 10,000 children (60% of them girls), indirectly reaching another 50,000 individuals (January 2014). The overall impact on the development of society is immeasurable. However, the interviews with children and the qualitative assessments in collaboration with the University of Chicago and USAID have shown that, in a short period of time, the attitude of young participants was transformed so that they enjoyed reading and grew to respect and even love books and really took advantage of the library.

Impact on Boys and Men

Boys who participate in WLR sessions learn to respect the leadership position of women. WLR’s assumption is that women’s empowerment involves not just educating women but also educating males to support and encourage them. This model is innovative in targeting boys as well, so that they grow up as supportive sons, husbands, brothers and fathers.

Impact on Parents

The model has a direct impact on parents who attend the read-aloud sessions. Thanks to WLR activities, parents realise the importance of reading aloud to their children.

Impact on Women and Girls

Every woman in charge of a library and reading sessions becomes a partner in the development of the programme. As a result, people start to respect women and support their roles as leaders. In the mosques they are accepted as mediators for advanced literacy skills. Female Palestinian refugees found that men from their neighbourhoods encouraged them in their new leadership position and people felt that those women could make a difference in their communities.

The training enables young women in their leadership role to critically examine their environment, identify problems in their community and come up with solutions. For example, in one neighbourhood, the women brainstormed how to dispose of the garbage. They created a compost pile which resulted in them saving money. Older women taking part in the programme feel a sense of fulfilment, because they have something to offer their community. One older woman, whose children were grown up, said that reading to the children of the community made her happier and gave her a sense of fulfilment.

The women also gain knowledge from reading literature other than children’s books, supporting them in ensuring their leadership plays an important role in decision-making within the community. This instigates change and can be considered as a longer-term impact of the programme.

Also, in the longer term, the programme advances a skilled and creative generation of girls who will become empowered mothers, while enhancing female volunteerism, independence and advocacy, and redefining the role of women, their sense of ownership, and the respect they are accorded.

Challenges

The biggest problem facing most projects working on raising awareness in developing countries is accessing the grassroots. Clearly, it is not possible to train all the parents to read aloud and develop passion for reading, but WLR uses the grassroots approach to build the capacities of one person in each neighbourhood who reads to children, ensuring that, in the long run, a passion for reading is transmitted to the next generation. Reading is used as a means of supporting children to become independent thinkers and making them aware that people can learn from others while maintaining pride in their own culture and heritage.

Another major challenge within this programme has been to raise funds and find appropriate books for the children. The books are bought through grants or are donated by other organisations. All books are screened by WLR to make sure they are age-appropriate and of high quality.

In the beginning it was hard to make the community believe in the positive impact of the programme. Before the sessions started, children hesitated, because they saw WLR as just another educational programme. After listening to the stories and having fun they attended the sessions more often and brought their friends and relatives with them.

As the number of children in the community attending the sessions increases, WLR continuously needs new volunteers, but it is hard to recruit them. Before the training starts many participants lack proficient reading skills. WLR supports these learners in improving their reading skills. The volunteers have to show high commitment in practising reading children‘s books with family or friends before the read-aloud sessions. A further challenge is the remaining stigma associated with illiteracy.

Innovation

The WLR model is innovative on multiple levels:

1) Storytelling is deeply rooted in Arab culture. WLR takes a systematic approach to harnessing this tradition in order to motivate people to practise reading;

2) The idea of community involvement and volunteerism is a new concept in Islamic Development Bank (IDB) member counties, especially for women;

3) The model also serves as a platform for dissemination of awareness programmes including hygiene, conservation of energy and water, etc.;

4) Research as shown that a mother can stimulate good habits in the daily life of her young child (for example, on health and environmental protection) if she reads to the child regularly; and

5) The WLR model is also unique in that it is sustainable thanks to the management of the libraries by women, which is why all the credit goes to them and not to WLR. This empowers the women and helps them to overcome the dominance of men in mosques by taking over leadership roles for the libraries in the mosque.

Lessons Learned

WLR states that every person who starts a library helps them to advance the model by sharing their personal experience. As the programme is continuously growing, the social entrepreneurship aspect of the training is increasing in importance.

WLR considers providing and reading books to be an important foundation which may enhance literacy. However, the key to improving literacy is building reading capacities and storytelling experiences.

For the volunteers it became crucial to talk about the experiences they gained during the story-telling sessions. As they live in different places, the appropriate tool for this exchange proved to be a Facebook platform. This means that more ideas and suggestions can be raised and areas for improvement can be more readily identified.

Sustainability

Certain activities are engaged in to maintain a sustainable financial situation; for example, training services, the selling of books and fundraising. Mosque leaders have donated money to buy books for the libraries. Because of capacity-building at the local level, the model works cost-efficiently. The programme uses and leverages local resources, such as volunteers, venues and books, instead of relying on external resources and ideas. This turns the local community into a stakeholder in the success of the library.

The WLR approach is easily replicable, particularly in rural areas, as there are only a few requirements, such as a trained reader, a small selection of books, a comfortable location and enthusiastic participants.

Moreover, WLR has developed and maintained diverse partnerships, locally and regionally, as well as internationally.

In order to advance the WLR model, the organisation has established multi-stakeholder relationships by working with local and private businesses as well as government. Furthermore, the model is being adopted in the Syrian refugee camps in Jordan as a way not only to foster a love of reading among children, but also to help them to cope with the frustrations and hardships of camp life. The libraries support a network for communication among library leaders and camp authorities and provide a space within which people can connect with each other.

Contact details

Rana Dajani

Founder and Director of Taghyeer

55 Abdel Hameed Badees Amman Jordan

Email: User: rdajani

Host: (at) welovereading.org

Website: http://www.welovereading.org

Sources

- Kidd, D. C., Castano E. (2013) “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind”, Science Vol. 342 (6156), pp. 377-380

- Leadbeater, C. (2012) Innovation in Education: Lessons from Pioneers Around the World, Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing

- Bal, P.M., Veltkamp, M. (2013) How Does Fiction Reading Influence Empathy? An Experimental Investigation on the Role of Emotional Transportation, PLoS ONE 8(1)

- Trelease, J. (2013) The Read-Aloud Handbook, 7th ed, Penguin Books: New York

- We Love Reading (2010), A Library in Every Neighbourhood: http://www.welovereading.org/ (accessed 17 March 2014)

Last update: 5 June 2014