The following article is authored by Christoph Lakner, Berk Özler, and Roy van der Weide of the World Bank.

The current COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is already negatively affecting the lives of the world’s poor and many of its vulnerable – both through lockdowns and through the widespread economic contraction. The long-term effects of this shock could be devastating for many poor and near-poor, not only in terms of immediate health risks and mortality, but also in terms of longer-term problems, such as stunting and lower human capital accumulation among children due to increased levels of malnutrition and stress among pregnant women and mothers. Rich countries are dealing with the difficult trade-off between lives and livelihoods by allocating unprecedented levels of resources towards cash transfers and expanded unemployment insurance for their citizens, support for businesses to keep their payrolls, and so on. Simultaneously, they are investing in public health efforts, such as improved testing and tracing capabilities, research on vaccines and antivirals, etc.

Low- and middle-income countries (LICs and MICs) also need massive injections of cash into their economies but cannot afford the types of measures adopted by high-income countries. One plausible way to finance such support to the world’s poor during what is most likely to be a protracted crisis is redistribution. This contribution to the UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab imagines a world in which rich countries agree to provide financial support for LICs and MICs during the crisis and outlines the broad strokes of how much such a hypothetical scheme might cost, how it could be financed, who could fund it, and how the money could be distributed across poor countries.

How much will it cost?

Given the size of the shock and agreement among many economists and public health specialists that the recession will not be short-lived (see blog with estimates of the income losses), we imagine that the scheme needs to be generous enough to be able to provide, on average, $1.90/day to 3.3 billion people for a period of six months, starting as soon as possible. Such support would need to be worth $ 1.14 trillion.[1]

How can it be financed?

In thinking about how this scheme could be financed, we look at the GDP of the entire G20, which is $ 80 trillion. Emergency relief worth $1.14 trillion accounts for 1.43% of the GDP of G20 and 2.95% of the GDP of the richest ten G20 countries (by GDP per capita). If each country contributed this percentage of their GDP as a one-time relief effort for poor countries, they would be able to assist 3.22 billion people residing in the world’s poorest 66 countries. For comparison, a $1.14 trillion aid package to the world’s poorest 66 countries would constitute only 4.0% of the wealth of the top 1% in the United States and 63.5% of the wealth of the world’s 50 richest people.

How could the COVID-response fund be allocated across 66 of the world’s poorest countries?

Using a well-known result in optimal geographic targeting to minimize poverty given a fixed budget (Kanbur, 1987), we propose allocating our budget by ranking all countries in the world using their poverty gap index, and making a lump-sum transfer to the poorest country that equalizes its poverty gap to that of the second poorest country by allocating the transfer equally and universally among all of its citizens; making lump-sum transfers to those two countries enough to bring their poverty gap index equal to the third poorest country, and so on – until the budget of PPP$1.14 trillion is exhausted.

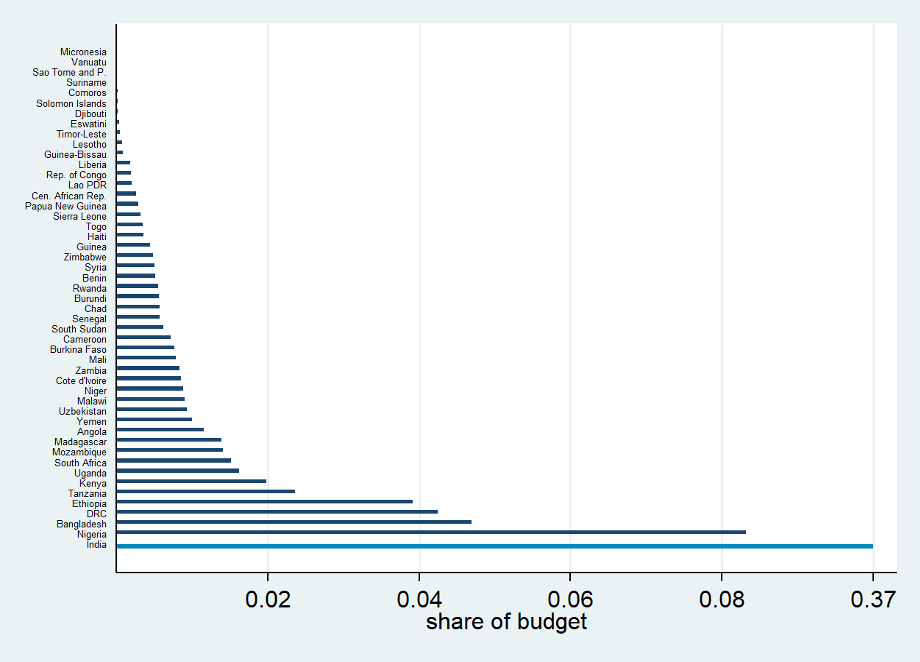

Figures 1-2 show how much 66 of the world’s poorest countries would receive under our optimization scheme. We can see that 37% of the funds would be flowing to India, which would offer all of its citizens $1.90 per day for almost six months. No other country receives more than 10% of the budget. India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan are the five countries receiving the highest shares of the budget (Figure 1), followed by DRC, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, and the Philippines. Interestingly, the median country assistance accounts for 12% of GDP (Figure 2) – a share that is very similar in relative magnitude to the emergency spending legislations passed in high-income countries like the United States or the EU.

Figure 1: Share of budget allocated to each country

Figure 2: Transfer as a share of GDP

Conclusion

As $1.9/day per person for six months would constitute generous hypothetical transfer amounts (compared with existing social safety net programs in LMICs), a non-negligible share of the aid could be directed by each country towards urgent public health investments, which could be paired with technical assistance from HICs, IFIs, and the WHO. We suggest that the remaining sums should be prioritized to establish or support existing transfer programs in each country – universal or targeted as appropriate to the setting in each country (see real-time overview of country social protection measures in response to the pandemic here). Such support could shield residents of poor countries, especially vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women, families with young children, and the elderly, from destitution, malnutrition, and poor health, and prevent irreversible long-term harm from the pandemic.

References:

Kanbur, S. R. (1987). Measurement and alleviation of poverty: With an application to the effects of macroeconomic adjustment. Staff Papers, International Monetary Fund 34(1), 60-85.

Notes:

[1] See here how we arrived at a budget of $ 1.14 trillion and the objective to cover 3.3 billion people:

https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/how-would-you-distribute-covid-response-funds-poor-countries.

…

Christoph Lakner is an Economist in the Development Data Group (Indicators and Data Services team) at the World Bank.

Berk Özler is a lead economist in the Development Research Group, Poverty Cluster at the World Bank.

Roy van der Weide is a Senior Economist on the Poverty and Inequality Research team within the Development Research Group of the World Bank.

The authors are responsible for the facts contained in the article and the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization.