22 HERITAGE SUSTAINABILITY: 0.70/1 (2013)

Swaziland’s result of 0.70/1 is reflective of the high level of priority given to the protection, safeguarding and promotion of heritage sustainability by Swazi authorities. While many public efforts are dedicated to national registrations and inscriptions, raising-awareness, and community involvement; select persisting gaps in conservation and management, capacity-building, and stimulating support amongst the private sector call for additional actions to improve this multidimensional framework.

The Swaziland National Trust Commission (SNTC) is the parastatal organization responsible for the conservation of nature and the cultural heritage of the Kingdom of Swaziland, operating under the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs. The SNTC was established by the SNTC Act of 1972. The National Museum, the National Monuments, Archaeology and Wildlife/Parks departments of the SNTC work in their respective capacities toward the protection and promotion of natural and cultural heritage.

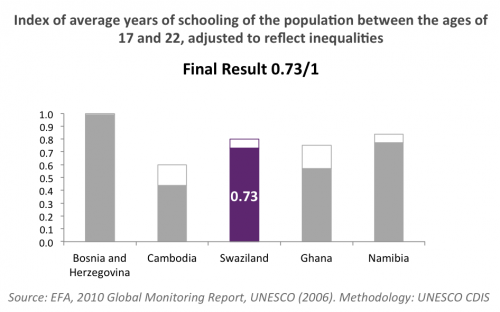

Swaziland scored 0.73/1 for registrations and inscriptions, indicating that authorities’ efforts have resulted in many up-to-date national registrations and inscriptions of Swazi sites and elements of tangible and intangible heritage. Swaziland has 79 items on the national registry of natural and cultural heritage, 1 of which, the Ngwenya Mines, was submitted in 2008 on the World Heritage Tentative List but has failed to complete the inscription due to the reopening of mining activities. In addition, though having only ratified the 2003 Convention in 2012, fifteen elements of intangible heritage have already been inventoried as part of the Flanders financed Projects on Community-based Inventorying of Intangible Heritage since 2011. Likewise, prior to the 2012 ratification of the 1970 Convention, stolen cultural objects were already part of a national register of stolen movable heritage and museum property.

Swaziland scored 0.67/1 for the protection, safeguarding and management of heritage, indicating that there are several well-defined policies and measures, as well as efforts to involve communities. Many recent efforts have been made to enhance the promotion of heritage, include the ratifications of the 1970, 1972, 2003, and 2005 Conventions, and the consequent review of national policies to accommodate new commitments such as those regarding intangible heritage. Regarding community involvement, the SNTC Act (1972) clearly states that heritage belongs to communities. As a result, the SNTC actively involves communities in the process of identifying tangible and intangible heritage, and traditional authorities are consulted in order to respect customary practices and the sacred nature of sites. Heritage site management is also entirely driven by community committees; the SNTC acts as an advisory body. However, notable gaps in the framework can still be identified. While recent policy changes have been made to better accommodate intangible cultural heritage, additional efforts are needed to adopt concrete policies and measures to prevent the illicit trafficking of cultural property. Other exclusions include the incorporation of heritage in the National Development Strategy, the existence of a specialized police unit for illicit trafficking and specific training efforts regarding the protection of cultural property in armed conflict.

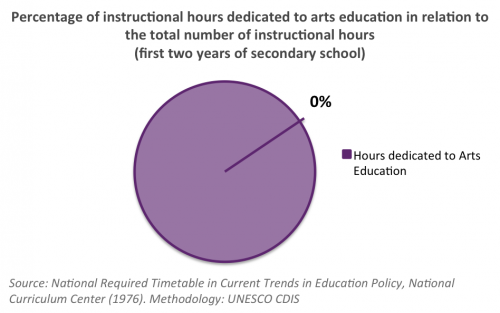

Swaziland scored 0.72/1 for the transmission and mobilization of support, which reflects efforts taken to raise awareness of heritage’s value and its threats amongst the population, as well as efforts to involve the civil society and the private sector. In addition to signage at heritage sites and differential pricing, awareness-raising measures include the SNTC’s radio programme to promote heritage and environmental issues, as well as the inclusion of heritage topics in school syllabi as early as Grade 4. While many means are used to educate the public, limited efforts are put into place to gain the support of the private sector. Though the SNTC is currently in the process of signing a memorandum of understanding with the Swaziland Television Authority to promote heritage, and efforts to form private foundations to assist in the protection of heritage have resulted in such groups as the Natural History Society, explicit agreements with tour operators is an additional means to be further explored. The Swaziland National Council of Arts and Culture Policy (2009) states as an objective to “draw and enter into memoranda of agreement with other countries and international organisations on the promotion of arts and culture.” This includes the promotion of heritage. The National Development Strategy (1997-2022) similarly calls for cooperation with neighbouring countries to promote tourism. Thus, formalizing existing tentative partnerships between South African tour providers and museum officers could enhance the framework for heritage sustainability.