Idea

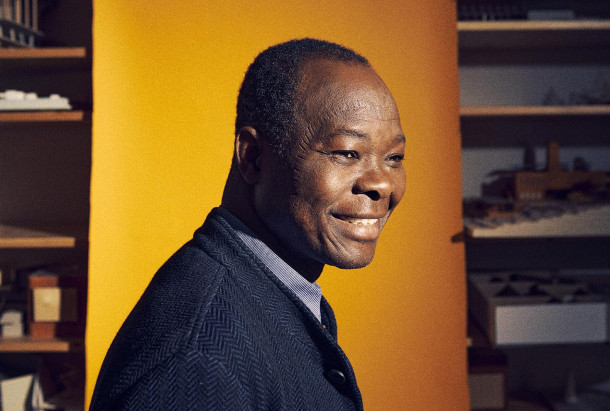

Diébédo Francis Kéré: “ I try to work alongside nature and not against it”

Interview by Laetitia Kaci

UNESCO

You were born in the village of Gando, in the centre-east of Burkina Faso. What led you to choose the profession of architect?

From the time I was an elementary school student I wanted to improve the classrooms in Burkina Faso. The ones I had to learn in were hot and crammed and dark. The desire to provide future generations of children with better learning conditions eventually led me to choose the profession of architecture.

I studied at the Technische Universität Berlin and adapted the knowledge I gained there to the context in which I wanted to build. My professors encouraged me to pursue the idea of improving traditional building methods and using local materials. But they also made me realize that the way I wanted to build was not just a private pursuit or something I personally cared about. Instead, it could offer an important contribution to the field of architecture in general.

One of your first projects was the school in Gando, which you chose to build with traditional materials such as raw earth, rather than cement or concrete blocks. What was your reasoning behind this approach?

I see myself as a material opportunist. I work with what is available and makes sense in the location I am building in. This can include concrete where and when it makes sense. I do this because one of my guiding principles is that the most important thing is to work with materials for which experts are available, so that buildings can be maintained with little effort and by local experts. I was able to try this in locations that a lot of contemporary architecture overlooks, and I can now bring this to wider-known contexts as a tried-and-tested method.

I work with what is available and makes sense in the location I am building in

The population was involved in this project and those that followed. What difference does it make?

It took a lot of conversation and making sure people felt included. The way I proposed to build was never done before. I proposed to build in a material that was well known but not valued very highly and I told them that I had learned to build at a university – whereas this is something you usually learn from your elders in Gando. I managed to convince everyone by doing trials together so I could showcase my ideas and prove that they work. I think there are many lessons here. One is the use of material. If you want to build somewhere with little resources, you shouldn’t just throw your hands up and say ‘well, then it can’t be done’ or ‘we need to bring things from elsewhere’. But rather let scarcity be your driver for innovation.

The other lesson is that you really need to spend the necessary time to include people. Do not make the mistake of believing that because you think you come bearing gifts, those who did not ask for them need to immediately be grateful. Trust comes from inclusion and participation. Not just from rational explanations. And solutions come this way too. Solutions you could not have thought of by thinking about a problem far away and without including those it concerns.

How do you manage to breathe life into a building?

Where possible I try to work alongside nature and not against it, which already brings a certain atmosphere to a space. This includes surrounding yourself with materials that feel like they come from nature and exploring how your domestic spaces can be multifunctional, creating spaces where people feel comfortable and like to spend time.

To what extent has architecture to do with social equality?

People and the world we live in are the start and end point of my work. If there is no one who needs a building, then why would I build one? And if no one uses what I have built, then what is the use? A space is only fully realized once it is used. Architecture that does not do this is somewhat disappointing. That is not to say it should not be extraordinary and push boundaries, try out new ideas and designs, but if it is to endure, living beings need to want to be in it. At least that is what I hope to achieve with my buildings.

You advocate for "coherent and peaceful cities". What do you mean?

Cities that feel like they are of and for the people. The more comfort cities can offer, through ample space where people can rest and gather, the more peaceful their citizens will be. It is a big challenge though, but one we are facing whether we like it or not.

The buildings you have created are characterized by energy sobriety, designed with local materials to resist heat. In a context marked by global warming, how is it that such practices are not more widely adopted worldwide?

For me it is such an essential aspect of what architecture needs to do today that it goes without saying that my designs are shaped by considerations of it. The important thing to me is that it is done in a comprehensive way so as not to just hop on the newest trend or to pay lip service to these topics without taking into consideration their immense complexity.

You are the first African laureate of the Pritzker prize, the highest honour of the profession. What does it mean to you?

It was an incredible surprise and even though it has been some months now since the announcement I simply still cannot believe it. The prize has made my voice a lot louder, and I feel that it is both an opportunity and a responsibility.

How do you see the future of ecological and locally-thought architecture?

I cannot answer this question alone. It will need many different experts in different localities willing to think about how to do things in a way that takes our planet and limited resources into consideration. What I do see is a generation that understands that great design and ecologically thoughtful architecture are not mutually exclusive but rather can inform each other. And maybe from there, we’ll be surprised by what’s possible.

Great design and ecologically thoughtful architecture are not mutually exclusive but rather can inform each other

You have designed buildings in your country, in Kenya, in Mali, in the United States, in Europe, in China… What’s next?

We just opened the Kamwokya Community Playground in Kampala, Uganda to the public – a project that has all the Kéré hallmarks. At the same time we continue building the National Assembly in Benin and there is always work to be done for the growing educational infrastructure in Burkina Faso.

We are also developing projects in Portugal, Germany and Togo and are simply grateful that we can continue exploring and bringing our approach to new locations.