CDIS | Namibie's indicators

La culture est importante en Namibie : les indicateur IUCD dévoilent le potentiel prospère du secteur culturel tout en soulignant certains obstacles en place qui l’inhibent et l’empêche d’atteindre son plein potentiel.

Les résultats suggèrent que malgré le niveau élevé de la demande de consommation en activités, biens et services culturels nationaux et étrangers 3 (9% du total des dépenses de consommation des ménages); le niveau de la production nationale est relativement faible, en particulier dans le secteur formel, illustré par un faible pourcentage d'emploi culturel 2 (0.65% de la population active totale). En outre, les faibles niveaux d'approvisionnement en productions nationales de fiction sur la télévision publique 21 (12.15% du temps de diffusion des programmes de fiction), reflètent indirectement le manque de possibilité pour la diffusion et l'exposition de contenus culturels fournis par les industries culturelles et les créateurs locaux. Ces chiffres soulignent le potentiel inexploité du marché du secteur de la culture en Namibie pourtant porté par la demande.

En ce qui concerne les liens entre l'éducation et la culture en Namibie, bien que les possibilités de formation professionnelle dans certains champs ne soient pas encore disponibles, les institutions publiques fournissent une offre assez diversifiée de programmes liés à la culture dans l’enseignement technique et supérieur 7 (0.7/1) ce qui reflète l'intérêt et la volonté d'investir dans l'éducation culturelle au niveau professionnel de la part des autorités namibiennes. D'autres données illustrent cependant le manque d’éducation artistique dans années de formation essentielles 6 qui peut entraver les intérêts, les compétences et les possibilités des individus pour poursuivre une carrière professionnelle dans le secteur de la culture, ce en dépit de la gamme de programmes spécialisés disponibles.

Bien que les résultats positifs aux indicateurs sur les cadres normatif, politique et institutionnel 8 9(0.7/1 ; 0.78/1) suggèrent que les fondements d'une bonne gouvernance culturelle sont en place, des obstacles persistent en ce qui concerne la participation de la société civile dans les processus d'élaboration des politiques 11 (0.25/1) et concernant la répartition inégale des infrastructures culturelles à travers les 13 régions de la Namibie 10 (0.33/1). Ceci limite non seulement les possibilités d'accès à la vie culturelle mais défavorise également les débouchés pour la production, la diffusion et le bénéfice de la culture.

Pour que la culture renforce sa contribution au développement par le biais de la cohésion sociale, l'accent devra peut-être être mis sur la promotion des perceptions positives de l'égalité des sexes pour le développement, ainsi que sur des actions ciblées pour résoudre les problèmes de confiance interpersonnelle. En effet, les résultats objectifs de l’égalité entre les sexes 17(0.8/1) ne se traduisent pas dans les opinions quant à son importance pour le développement. De même, il subsiste un écart entre les indicateurs sur la tolérance envers les autres cultures et ceux sur la confiance interpersonnelle et interculturelle 15 (12%), qui sont directement liés à la cohésion sociale et d'une importance particulière dans le contexte de l'après-apartheid.

Vous trouverez ci dessous le Résumé Analytique détaillé disponible en anglais uniquement.

1020

2 CULTURAL EMPLOYMENT: 0.65% (2008)

In 2008, 0.65% of the employed population in Namibia had cultural occupations (4447 people: 29% male and 71% female). 88% of these individuals held occupations in central cultural activities, while 12% held occupations in supporting or equipment related activities.

While already significant, the global contribution of the culture sector to employment is underestimated in this indicator due to the difficulty of obtaining and correlating all the relevant data. This figure is only the tip of the iceberg since it does not cover non-cultural occupations performed in cultural establishments or induced occupations with a strong link to culture, such as employees of hospitality services located in or close to heritage sites. In addition, this does not account for employment in the informal culture sector, which is likely to be significant in Namibia. Furthermore, because the raw data in Namibia is only available to the three-digit level of international standard classifications, certain central cultural occupations are not taken into account.

Regardless, this figure highlights low levels of formal cultural employment in Namibia, suggesting that levels of domestic cultural production in the formal sector are also rather low. The relevance of the priorities set aside in the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture and the former National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012), oriented to increase production and optimize the economic contribution of the culture sector, is thus underlined.

1021

3 HOUSEHOLD EXPENDITURES ON CULTURE: 9.09% (2009/2010)

In Namibia, 9% of household consumption expenditures were devoted to cultural activities, goods and services in the year of 2009/2010 (1400.26 NAD). It is likely that this final result is an over-estimation of the actual percentage of household consumption expenditures spent on culture due to the current limitations of national data systems which are not exhaustive but rather based on sample groups. As Namibia remains a country of significant divides, often the most isolated groups of the population are not accurately reflected in such data sets due to inaccessibility. The average across all test phase countries of the CDIS is 2.43%, which also suggests that Namibian figures may be overestimated.

Despite the underlined methodological challenges, the national result obtained suggests that there is a real and significant demand from Namibian households for the consumption of foreign and domestic cultural goods, services and activities, and of this 55% is spent on central cultural goods and services, 45% being left to supporting activities and equipment. On average nation-wide, in the category of central cultural goods and services, the most was spent on daily and weekly newspapers (139.45 NAD), watches and personal jewelry (156.90 NAD), and subscription television (292.16 NAD). In the category of support and equipment, a significant share was spent on television sets, decoders, DVD players, and video players (169.95 NAD); and personal computers and laptops (213.16 NAD).

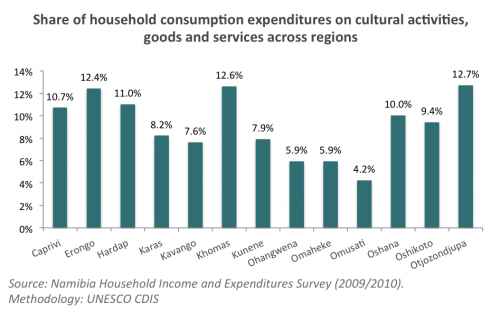

The share of consumption expenditures varies greatly from one region to another in Namibia, from 12.7% and 12.6% in Otjozondzupa and Khomas to 5.9% and 4.2% in Ohangwena and Omusati.

>> While the Economy indicators suggest that there is a significant potential demand for the consumption of cultural goods, services and activities, they also suggest that there is a low level of domestic production in the formal sector, illustrated by the low levels of employment. This is reinforced when cross-analyzing the dimension with other CDIS indicators such as the Diversity of Fictional Content on Public TV, which also suggests low levels of domestic content supply in public broadcasting. High demand and low domestic production would indicate that the full economic potential of the culture sector in Namibia is not being realized.

1022

1023

Article 19 of the Constitution of the Republic of Namibia states that “every person is entitled to enjoy, practice, profess, maintain and promote any culture, language, tradition or religion” so long as it does not impinge upon the rights of others. Furthermore, the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture states that the government has the mission and goal to uphold unity in diversity so that all Namibians feel free to practice any culture, recognizing that such “unity is maintained by mutual understanding, respect and tolerance.” As part of promoting this unity in diversity, the 2001 Policy also states that it is the goal of the Namibian government to safeguard and promote linguistic heritage and acknowledges the role of education in the promotion of cultural diversity. Though not reiterated in the National Development Plan 4 (2013-2017), the National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012) recognized that “language is an essential carrier of culture” and that the biggest challenge post-independence was to heal the wounds of inequality and racism and recognize the wealth of Namibia’s multiculturalism.

According to the national curriculum for education, updated in 2010, 55.6% of the hours to be dedicated to languages in the first two years of secondary school is to be dedicated to the teaching of the official national language- English. The remaining 44.4% of the time is to be dedicated to the teaching of local and regional languages. Although, the fact that 0% of the required national curriculum is dedicated to additional international languages, such as French or German, these results still indicate that the national curriculum is designed to promote linguistic diversity in Namibia, particularly regarding the promotion of local languages and mother tongues. It should be noted that learners have the option of taking additional international languages such as French or German as one of the prevocational subjects of their choosing.

However, in spite of the promotion of diversity, of the 11 nationally recognized local and regional languages, only 9 are taught in schools. Otjizemba and Ju!hoansi are the only remaining nationally recognized local languages that are not promoted in the education system.

1024

6 ARTS EDUCATION: 2.4% (2010)

The 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture’s stance on “unity in diversity” recognizes that Namibians see themselves as a united nation celebrating the diversity of their artistic and cultural expressions and declares as a goal that the status of the arts should be improved through education and that arts subjects should therefore be part of the new curriculum. The policy goes on to state that in such an environment “learners are sure to acquire many skills and self-confidence through exploring their own creative abilities” and that it is “necessary to reverse an alarming trend for the downgrading of the arts and culture.” National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012) also recognized that arts education was necessary for the realization of the country’s creative potential and that a priority should be to “establish a solid foundation of education in the arts and culture.”

Contrasting with the policy statements, the results for this indicator reflect a rather low level of promotion of arts education. According to the updated curriculum of 2010, only 2.4% of the total number of instructional hours is to be dedicated to arts education in the two first years of secondary school (covered by one subject entitled ‘Arts-in-culture’). It should be noted, however, that in addition to the required hours to be dedicated to the arts, learners have the option of taking one additional course entitled ‘Visual and integrated performing arts’ as one of the prevocational courses of their choosing. Nevertheless, this result indicates that instructional hours dedicated to arts education in secondary school remains low, especially when taking into account the average across all test phase countries of the CDIS, which is around 4.84%.

Furthermore, a gap in the offerings of arts education over the course of the educational lifetime emerges. On average, 6.2% of all educational hours are to be dedicated to arts education in primary education. This is nearly three times what is required during secondary education. Moreover, when looking at the following indicator on tertiary and training programmes that are offered in Namibia in the field of culture, it can be noted that the coverage is fairly complete. This gap in arts education during secondary schooling may obstruct both students’ interest in developing a professional career in the culture sector and also concrete opportunities in accessing existing specialized programmes.

1025

7 PROFESSIONAL TRAINING IN THE CULTURE SECTOR: 0.7/1 (2012)

In the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture, a key goal was defined to improve the status of the artist “through education and training, and by exploring the economic potential” of the culture sector. The essential link between education, training and employment was made. Namibia’s result of 0.7/1 indicates that though complete coverage of cultural fields in technical and tertiary education does not exist in the country, the national authorities have manifested an interest and willingness to invest in the training of cultural professionals. Indeed, the coverage of national public and government-dependent private technical and tertiary education is rather comprehensive in Namibia, offering various types of courses and permitting cultural professionals to receive the necessary education to pursue a career in the culture sector.

Tertiary education is offered by the University of Namibia in the fields of heritage, music, visual and applied arts, and film and image. The College of the Arts also offers technical training in the fields of music, visual and applied arts, and film and image. In addition, the Namibian Training Authority offers one training program in garment making, which falls under the category of visual and applied arts. Although this collection of offerings is fairly inclusive, it is not complete. For instance, no regular technical training programmes exist in the field of heritage, and no technical or tertiary education programmes exist in the field of cultural management, a key area for fostering the emergence of domestic cultural enterprises and industries.

1028

8 STANDARD-SETTING FRAMEWORK FOR CULTURE: 0.70/1 (2013)

Namibia’s result of 0.70/1 indicates that the country is on the right track and has made many efforts to ratify key international legal instruments affecting cultural development, cultural rights and cultural diversity, as well as to establish a national framework to recognize and implement these obligations.

Namibia scored 0.59/1 at the international level, which shows movement in the right direction. Namibia has ratified several important conventions such as the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the 2005 Convention of the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, all of which are particularly important to the Namibian cultural context. Namibia is still working towards the ratification of certain key international instruments for the protection of cultural assets, such as the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, and the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

At the national level, a score of 0.75/1 indicates that national efforts have been made to implement many of the international obligations that Namibia has agreed to at the country level. However, similar to the international level, room for improvement still remains as several key items continue to be missing from the national legislation and regulatory frameworks. For example, no ‘framework law’ for culture exists, and although a sectoral law exists for television and radio, no such laws exist for other sub-sectors such as heritage, books, cinema or music. In the same vein, the lack of regulations dealing with the tax status of culture, such as tax exemptions and incentives designed to benefit the culture sector specifically, also reveals some deficiencies in the establishment of a coherent normative system for supporting the emergence of viable domestic cultural industries that could respond to the proven demand.

1029

9 POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR CULTURE: 0.78/1 (2013)

The final result of 0.78/1 reflects that national authorities are progressing in the creation of a policy and institutional framework promoting the culture sector as part of development by establishing targeted policies and mechanisms and by having an adequate political and administrative system to implement the legal instruments seen above. Indeed, though not quite there, Namibian results are progressing in the direction of achieving a result consistent with the average of test phase countries of the CDIS for this indicator, which is 0.79/1.

The Ministry of Youth, National Service, Sport and Culture has the mandate for the overall formulation, implementation and management of cultural activities. The ministry’s efforts are reinforced by cultural institutions, such as the National Theatre of Namibia, the National Arts Council and the National Heritage Council, intended to promote specific cultural sectors.

Namibia scored 0.82/1 for the Policy Framework sub-indicator, indicating that there are many well-defined sectoral policies to promote the culture sector in the country. Namibia also has a general cultural policy, the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture, which guides the ministry and its affiliated institutions’ actions. However, there is for instance no sectoral policy for music. In addition, culture has not been included in poverty reduction strategy papers (PRSPs) or previous United Nation Development Assistance Frameworks (UNDAF), and although culture was integrated in the former National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012), it no longer appears in National Development Plan 4 (2013-2017).

Namibia scored 0.75/1 for the Institutional Framework sub-indicator, which assesses the operationalization of institutional mechanisms and the degree of cultural decentralization. Many positive factors account for such a result. Even though Namibia has a Ministry that covers the programmatic area of culture, cultural responsibilities have been decentralized to the regional level. A system of public subsidies exists for the sector, and public officials have been offered training in the sector within the last year. The remaining areas for improvement account for the imperfect score. Although, responsibilities have been decentralized to the regions, no specialized structures for culture are in place at the regional or local levels, and the budget remains centrally controlled by the government. Instead of decentralizing the budget, when planning events, the central government works closely together with the culture officers of the regional councils of all 13 regions of Namibia.

1030

10 DISTRIBUTION OF CULTURAL INFRASTRUCTURES: 0.33/1 (2013)

One of Namibia’s 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture goals clearly sets as an objective that Namibians take part in cultural and creative activities and different art forms to share their different understandings of life, release their creative potential and contribute to economic development. However, the distribution of cultural infrastructure in Namibia, which would facilitate such participation, paints a picture of important challenges to be faced.

On a scale from 0 to 1, Namibia’s result for this indicator is 0.33, 1 representing the situation in which selected cultural infrastructures are equally distributed amongst regions according to the relative size of their population. The score of 0.33 thus reflects that across the 13 regions of Namibia, there is an unequal distribution of cultural facilities.

When looking at the figures for the three different categories of infrastructures, Namibia scores 0.49/1 for Museums, 0.03/1 for Exhibition Venues Dedicated to the Performing Arts and 0.47/1 for Libraries and Media Resource Centers. This suggests that the most equal distribution of access exists for Museums and Libraries, and that the most unequal distribution of infrastructures exists for Exhibition Venues Dedicated to the Performing Arts, the Khomas region being the only region of 13 to have such facilities. While the Khomas region, the region of the capital city of Windhoek, benefits from a higher concentration of cultural infrastructures, other regions such as Omaheke, Kavango, Omusati and Oshana have no Exhibition Venues, and a rather low coverage for Museums and Libraries and Media Resource Centres. Building cultural infrastructures and increasing equality of access across all 13 regions could increase Namibians’ opportunities to take part in cultural and creative activities, release their creative potential and participate in economic development through the production and consumption of cultural goods and services, as stated in the 2001 Policy. This is a crucial and common challenge among all the countries that have implemented the CDIS until now, as the average score for this indicator is only 0.43/1.

1031

11 CIVIL SOCIETY PARTICIPATION IN CULTURAL GOVERNANCE: 0.25/1 (2013)

The final result of 0.25/1 indicates that there are few opportunities for dialogue and representation of civil society actors in regards to the formulation and implementation of cultural policies, measures and programmes that concern them. While Namibia received a score of 0.5/1 for the participation of minorities, a score of 0/1 was established for the participation of cultural professionals.

Regarding the participation of minorities, mechanisms exist at the national level to facilitate their participation in the formulation and implementation of cultural policies, measures and programmes that concern them. Furthermore, these mechanisms are permanent in nature and their decisions are binding. For example, the Division San Development is a national programme established by Cabinet decision No. 25th/29.11.05/001 and No. 9th/28.05.09/005. As part of the program, minorities are recognized as stakeholders and are to be involved in any decision that may affect them, including those of a direct or transversal cultural nature. However, at the regional and local levels no such institutional mechanisms or organic structures provide a framework for regular minority participation.

In Namibia, there are currently no associations, platforms, networks or other mechanisms in place to regularly involve cultural professionals in processes related to the formulation and implementation of cultural policies, measures and programmes that concern them. Such mechanisms would greatly assist in creating and enacting necessary and effective policies that correspond to the needs of the culture sector community. The absence of such mechanisms is a significant weakness in Namibia’s cultural governance and an obstacle for fostering a vibrant culture sector that realizes its full potential.

The adoption of legislation on non-profit cultural bodies, such as cultural foundations and associations, which are currently inexistent as highlighted by the indicators of this Dimension, could be a first step to foster the structuring of a professional culture sector.

1035

14 TOLERANCE OF OTHER CULTURES (ALTERNATIVE INDICATOR): 71.1% (2001)

In 2001, 71% of Namibians agreed that they can usually accept people from different cultures. In that same year, the Policy on Arts and Culture stated that the post-apartheid and post-independence vision of Namibia is to be a “united and flourishing nation, achieving sincere reconciliation through mutual respect and understanding, solidarity, stability, peace, equality, tolerance and social inclusion.” The 2001 Policy also recalled that “before independence people were divided and the majority discriminated against on the basis of race and culture,” whereas the “founders of …[the] new nation wisely saw in …[their] diversity of cultures a source of wealth through which we could unite in a common commitment to build the nation.” This objective for mutual understanding and tolerance of all cultures was reiterated in the National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012).

Within this context, the results of 71% for this alternative indicator suggests that the values, attitudes and convictions of more than two thirds of Namibians favor the acceptance of other cultures in the post-apartheid era. In addition, in the same survey, 74% of Namibians agreed that beyond accepting other cultures, they agree that exposure to other cultures enriches their own lives. This result further suggests a cultural system of values is in place that thrives on diversity, fosters tolerance, and encourages an interest in new or different traditions, thus creating a social environment favorable to development.

However, in spite of these positive results pointing to high levels of acceptance and tolerance of other cultures, another question from the same survey showed that this tolerance and acceptance does not translate into trust of other cultures. Only 37% of Namibians responded that it is easy to trust a person from a different culture, and though Namibia’s result is higher than the Southern African regional average (24.5%), this figure still indicates that there is a gap between tolerance and acceptance and trust of other cultures, thwarting an ideal context for social progress and development. Less than half of the Namibians that showed an interest in other cultures and demonstrated tolerance toward others, answered that it was easy to trust a person from another culture.

1036

INTERPERSONAL TRUST: 12% (2008/2009)

In 2008/2009, 12% of Namibians agreed that most people can be trusted. Within the context described above, this indicator further assesses the level of trust and sense of solidarity and cooperation in Namibia, providing insight into its social capital. A result of 12% indicates a low level of trust and solidarity as the average of the countries having implemented the CDIS is situated at 19.2%. Furthermore, though all groups of the population show low levels of trust, there are significant variations in the results for men and women and across age groups. Only 10% of women agree that most people can be trusted compared to 15% of men, and the results for different age groups vary from 11% of the people ages 30-49 to 20% of the people 65+, suggesting an increasing trend with age. Regardless, all of these figures remain rather low, and when combined with the alternative indicator presented above, these figures suggest that there remains an obstruction to fostering trust in the fabric of Namibia’s society in spite of the basis for tolerance being in place shortly after independence. This indicates that building on culture’s potential to further reinforce the feelings of mutual cooperation and solidarity amongst Namibians, and as a consequence, nurture social capital, deserves to be considered as a priority in modern Namibia through the development of targeted measures and programmes.

The conflicting results between tolerance and trust for this dimension suggest that much work still remains in this area and it is recommended to not only reintegrate social priorities in national development plans, but also to integrate relevant cultural and social questions into regular national surveys in order to establish consistent statistics and monitor progress throughout the implementation of the National Development Plan 4 (2013-2017).

1026

17 GENDER EQUALITY OBJECTIVE OUTPUTS: 0.84/1 (2013)

The Constitution of the Republic of Namibia states that “No persons may be discriminated against on the grounds of sex…” (Art 10). The Constitution also states that “it shall be permissible to have regard to the fact that women in Namibia have traditionally suffered special discrimination, and that they need to be encouraged and enabled to play a full, equal and effective role in the political, social, economic and cultural life of the nation” (Article 23(3)), and that the state should actively promote the “enactment of legislation to ensure equality of opportunity for women, to enable them to participate fully in all spheres of Namibian society” (Article 95 (a)). Such a priority for Gender Equality is reiterated in the National Development Plan 3 (2007-2012), and again in the National Gender Policy for 2010-2020 amongst other national policy documents.

The result of 0.84/1 reflects the significant efforts made by the Namibian government in order to elaborate and implement laws, policies and measures intended to support the ability of women and men to enjoy equal opportunities and rights.

A detailed analysis of the four areas covered by the indicator, reveals major gaps where additional investment is needed to improve gender equality basic outputs. A comparison of the average number of years of education for men and women aged 25 years and above reveals little divergence. Although this is a positive result, in that both genders have opportunities to gain the basic skills and knowledge, further research should be conducted to measure the gender equality rate for superior education where disparity may remain. Progress still needs to be made regarding labour force participation; where 63% of men are either employed or actively searching for work, versus 52% of women. Additionally, the adoption and implementation of targeted gender equity legislation focused on violence against women and a quota system for political participation needs to be improved. Finally, the most significant gap is observed regarding the outcomes of political participation where a major imbalance persists. Indeed, while women benefit from much higher global representation at the local authorities level, in 2012, they represented only 24% of parliamentarians. Moreover, both at the local and national levels of government, a very small minority of women hold positions of leadership such as Mayor, Deputy Minister or Minister. Nevertheless, “as a signatory to the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development, the Government has committed itself to achieving the target of 50% representation of women in decision-making positions by 2015” as stated in the National Gender Policy of 2010-2020. Effective efforts in this area will be necessary as “Women’s equal participation in decision-making is not only a demand for simple justice or democracy, but also ought to be seen as a necessary condition for women’s interests to be taken into account and for social and economic development,” as stated in Namibia’s 2nd Millennium Development Goals Report for 2008.

In Conclusion, while Namibia is doing well in terms of targeted objective outputs, gender equality is far from being achieved. The 2008 MDG report highlights that “Policies supporting gender equality and women’s empowerment are by no means lacking. The problem is rather how to implement these policies, and to change perceptions about women and their roles in society.” Policies require people, and a further look into the additional subjective indicators below reveals the persistence of negative cultural values, attitudes and practices in Namibia, which reinforce the subordinate role of women and hamper their full and equal participation in all spheres of life.

1027

18 PERCEPTION OF GENDER EQUALITY (ADDITIONAL INDICATORS)

84% of married women in Namibia feel that they have a say in how their own cash earnings are spent, either individually or jointly with their husbands. This data from the Demographic and Health survey suggests that employment is a source of empowerment for Namibian women. Similarly, 78% of the population (men and women) felt that women have a role in household decision-making regarding areas such as major household purchases, purchases of daily needs and visits to her family.

Room for improvement still remains. Perhaps the most surprising figure is that only 15% of men believe that it is acceptable for their wives to decide to visit their families on their own. Serious negative culturally based perceptions on gender equality and the role of women in the society persist in other key areas such as violence against women. Indeed, only 62% of the population believe that a husband is never justified in beating his wife; the other 38% of the population agrees that beating one’s wife can be justified for the following reasons: she burns the food, argues with him, goes out without telling him, neglects the children, or refuses to have sexual intercourse with him. An astoundingly low figure of 65% of women agree that being beaten can never be justified, while an even lower 60% of men agree with this statement. The most significant variation is across age groups, ranging from 56% of the population between the ages of 20-29 to 70% of the population ages 45-49 agreeing that domestic violence is never justified. This indicates that domestic violence is not only accepted by over one third of the population, but more widely accepted amongst the youth population.

In any context, violence against women is a key issue for gender equality, but in Namibia it is also a key topic linked to a national health priority: the spread of HIV/AIDS. In this sense, Demographic and Health Surveys in Namibia reveal that only 74% of the population agreed that a woman has the right to refuse sexual intercourse, and again the youth population showed the lowest numbers. Only 70% of the youth ages 15-19 responded that women have this right. These figures reveal that “the revision of certain cultural practices, especially those that disadvantage women and children, is essential in addressing the spread of HIV/AIDS and domestic violence,” as stated in the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture, and prioritized in the National Development Plan 4 (2013-2017).

>> This cross-analysis of the subjective and objective indicators reveals that a gap still remains in Namibia between the implementation of forward-looking public actions in advancing gender equality and the population’s attitudes and values in this area. Targeted cultural and educational measures are needed to instill ownership and understanding of how gender equality is beneficial for all. In this sense, the 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture stated that “while the valid things from the past must be preserved, there are practices in all of our cultures which must be changed, especially when these are in conflict with the rights enshrined in our Constitution or with internationally accepted ethics or the common good,” and recognized the significance of such cultural change in regards to ongoing gender issues.

1016

19 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION: 68/100 (2012)

The Constitution of the Republic of Namibia, adopted in 1990, states that “all persons shall have the right to: freedom of speech and expression, which shall include freedom of the press and other media” (Article 21.1).

Namibia’s score of 68/100 indicates that their print, broadcast, and internet-based media is currently ‘partly free’, falling just below the benchmark of ‘free’ media. This score illustrates the efforts made to support an enabling environment in Namibia for free media to operate and in which freedom of expression is respected and promoted. Such an environment is a condition for fostering the free flow of ideas, knowledge, information and content, for building knowledge societies, and enhancing creativity, innovation and cultural diversity.

However, room for improvement remains in the current legal environment of Namibia. Freedom of expression is curbed by the absence of legislation in regards to the access of public information and the Protection of Information Act of 1982. The Communications Act passed in 2009 was to improve the situation, but a number of clauses continue to fall short of international standards (African Media Barometer, 2011). Moreover, an additional subjective indicator reveals that, in 2008, 58% of Namibians agreed that they are free to say what they think. Therefore, as a whole, 32% of Namibians do not feel that they are free to fully exercise their freedom of expression, thus reinforcing the statement that improvements can still be made in order for individuals to be able to fully enjoy the freedom of expression.

Finally, while 62% of men agree that they are able to freely express themselves, only 53% of women feel that their freedom of expression is fully assured. Such results merit consideration when analyzing other dimensions, particularly regarding Gender Equality.

1017

20 ACCESS AND INTERNET USE: 12% (2012)

In 2012, only 12% of the national population used the Internet in Namibia. When compared to the regional average for all of Sub-Saharan Africa (48 countries), 12.56%, Namibia’s results are slightly below this regional average and fall in the middle of the results of its direct neighbors.

The 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture recalled that though “we may be concerned with our unique heritage, culture remains a dynamic phenomenon, and one which is more associated with social change. Arts and culture must therefore take new forms and use new media and technology, especially to attract and engage the young, so that we have a sense of our roots but are also engaged in contemporary expressions and ways of life.” Namibia’s National Development Plan 4 (2013-2017) also recognizes the importance of ICTs for economic growth.

Despite the recognition of the key role that access to digital technologies, in particular the Internet, plays in boosting the economy and encouraging new forms of access, creation, production, and the dissemination of ideas, information and cultural content, Namibia has a rather low result that may reflect the need to increase investments in the development of infrastructures, policies and measures that facilitate the use of new technologies. The country may also need to address issues such as pricing, bandwidth, skills, public facilities, content and applications targeting low-end users in order to bring more people online.

1018

21 DIVERSITY OF FICTIONAL CONTENT ON PUBLIC TELEVISION: 12.15% (2013)

In Namibia, approximately 12.15% of the broadcasting time for television fiction programmes on public free-to-air television is dedicated to domestic fiction programmes.

The 2001 Policy on Arts and Culture recognized the Namibia Broadcasting Corporation’s (NBC) impact on citizens’ cultural and artistic life, and the role it plays in disseminating domestic arts and culture. Indeed, programming domestic production, and particularly fictions with a high share of cultural content, may increase the population’s level of information on national events and issues, while also helping to build or strengthen identities and promoting cultural diversity. Moreover, public broadcasting has major implications for the development of the domestic audio-visual industry, as well as for the flourishing of local cultural expressions and creative products.

However, the results indicate a rather low percentage of supply of domestic fiction production (including co-productions) within public broadcasting, indirectly reflecting low levels of public support of the dissemination of domestic content produced by local creators and cultural industries. In addition, it should be noted that the majority of domestic fiction programmes target a youth audience, while few adult content categories are supplied by domestic productions.

An additional indicator on the diversity of creative content in public television programming, including both fiction and music programmes on public free-to-air television, reveals that when including musical productions made for television, the ratio of domestic creative content increases to 15.23%.

These result merits being taken into account when analyzing other indicators concerning cultural production, such as those of the Economy dimension, which also suggest low levels of domestic production compared to the levels of cultural content consumed by the public.

1032

22 HERITAGE SUSTAINABILITY: 0.61/1 (2013)

Namibia’s result of 0.61/1 is an intermediate result regarding the establishment of a multidimensional framework for the protection, safeguarding and promotion of heritage sustainability. The degree of commitment and action taken by Namibian authorities is mixed and varies according to the component of the framework. While many public efforts are dedicated to raising-awareness and community involvement, persisting gaps regarding national and international level registrations and inscriptions, as well as mechanisms for stimulating support amongst the private sector, call for additional actions to improve the framework.

The National Heritage Council (NHC) is a statutory organization responsible for the protection of Namibia’s natural and cultural heritage, intended to reinforce the work of the Ministry of Youth, National Service, Sport and Culture in matters regarding heritage. The NHC was established under the National Heritage Act, No. 27 of 2004, replacing the former National Monuments Council. In addition to the work of the NHC, the National Museum of Namibia maintains extensive collections of objects related to Namibian natural history, cultures, history, and archaeology, as well as actively pursues research to improve the content and understanding of its collections.

Namibia scored 0.54/1 for registration and inscriptions, indicating that while efforts have resulted in sub-national and national registration and inscription of Namibian sites and elements of tangible and intangible heritage, increased focus should be placed on updating national registries. Namibia has 129 heritage sites on their national registry, 2 of which have already received the recognition of being World Heritage, Twyfelfontein (2007) and the Namib Sand Sea (2012). In addition, thirteen elements of intangible heritage have already been documented in nine of Namibia’s regions. Such recent efforts suggest that Namibia’s catalogues of natural and cultural heritage are in the process of improving, as demonstrated by the recent efforts to achieve recognition of a second world heritage site, as well as actions to raise awareness and involve communities in the documentation of intangible cultural heritage. However, no database of stolen cultural objects yet exists and increased efforts could be made to update national registries and eventually achieve a higher degree of international recognition of Namibian heritage.

Namibia scored 0.61/1 for the protection, safeguarding and management of heritage, indicating that there are several well-defined policies and measures, as well as efforts to build capacity and involve communities. The NHC actively involves local communities in the process of identifying tangible and intangible heritage, and traditional authorities are consulted in order to respect customary practices when promoting intangible heritage. However, notable gaps in the framework can still be identified. While the National Heritage Act of 2004 protects cultural and natural heritage, intangible heritage was only included following the recent review process in 2011. Other exclusions include the existence of a specialized police unit for illicit trafficking of cultural objects and the publication of regularly updated management plans for major heritage sites. Concerning training and capacity building, while the training efforts against illicit trafficking are to be applauded as the country has yet to ratify the 1970 UNESCO Convention, gaps persist concerning concrete mechanisms to combat against illicit trafficking and building communities’ capacities in the safeguarding of intangible heritage.

Namibia scored 0.66/1 for the transmission and mobilization of support, which reflects the recent efforts taken to raise awareness of heritage’s value and its threats amongst the population and youth, as well as efforts to involve the civil society and the private sector. In addition to signage at heritage sites and differential pricing, awareness-raising measures include the Know Namibia programme in schools and Heritage Week, which is promoted nationally through public broadcasting as well as festivals. The NHC has also launched a website in April of 2012 to facilitate public awareness, with the support of the Millennium Development Goal Achievement Fund. While many means are used to educate the public, limited efforts are put into place to gain the support of the civil society and private sector. Additional efforts to form private foundations to assist in the protection of heritage and explicit agreements with tour operators are two means to be further explored.